CRAB FEST -ACT FOUR: The Claw Who Came to Dinner

“Tell me what you eat and I will tell you who you are.”

― Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin

The Claw at the Table

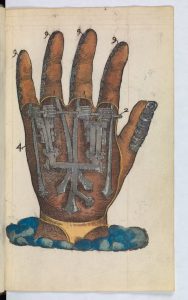

Born into a wealthy family, Alexandre Balthazar Laurent Grimod de La Reynière (1758 – 1837) entered the world with deformed hands, his fingers fused so that they looked like the stumpy claws of a crab without their shell. It was most likely the congenital malformation known as Cenani-Lenz Syndrome. He wore ingenious prosthetic hands designed by Swiss clockmaker Henri-Louis Jaquet-Droz, so that he could eat and write. When in company, he is said to have kept them permanently hidden under white gloves.

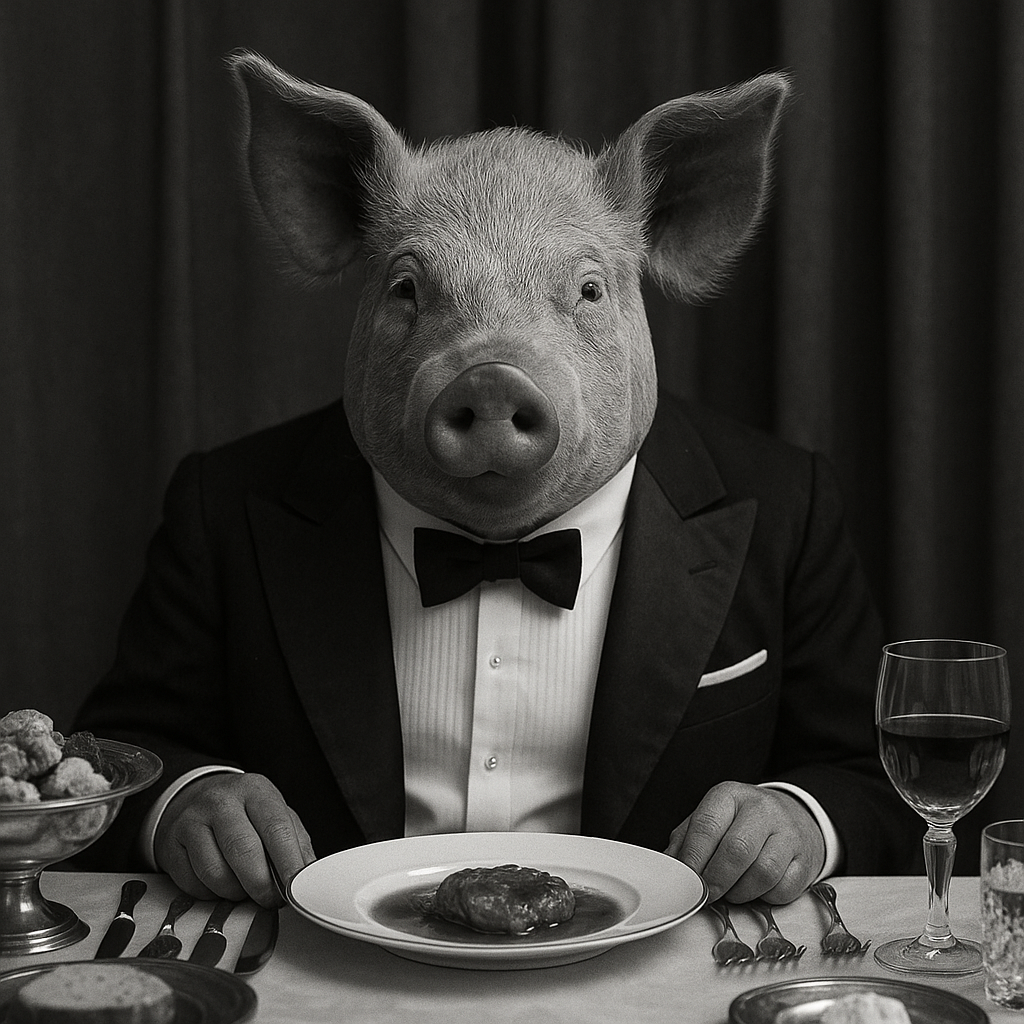

His father, a wealthy Parisian tax collector, and his mother, an aristocrat, were embarrassed and hid the child away from public view. Not wishing it to be known that the boy had inherited his condition and thus tarnish the reputation of their lineage, they fabricated a lie. The story was told that as a baby, Grimod had accidentally been dropped into a pig pen, the pigs quickly nibbling away at the infant’s fingers.

Grimod was schooled in isolation, and it is here that he is said to have developed his razor-sharp wit and famously dark sense of humour. Later, he studied law in Lausanne. He would infuriate his parents when he failed to close his law firm and to take up the higher position as a magistrate.

Culinary historian Cathy Kaufman, who coined the term ‘The Claw at the Table’ for Grimod, also wrote that his “louche lifestyle and republican politics infuriated his parents,” and instead of becoming a judge, he preferred to do pro bono work for those battling with tax law. According to Natasha Frost in Atlas Obscura, he is said to have remarked, “As a judge, I could find myself in the position of having to hang my father, while as an advocate, I would always be able to defend him.”

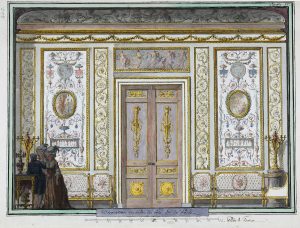

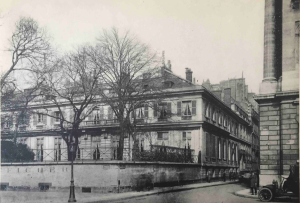

In 1775, his father commissioned a grand new house, Hôtel Grimod de La Reynière, at the corner of avenue Gabriel and rue de la Bonne-Morue. To the south, the house faced the Champs-Élysées gardens.

When his parents were away, the young Grimod threw parties that were soon the talk of the town, not for their refinement and grandeur, but for their notorious, even scandalous nature, as they mocked, ridiculed high society, and exhibited a dark and satirical humour.

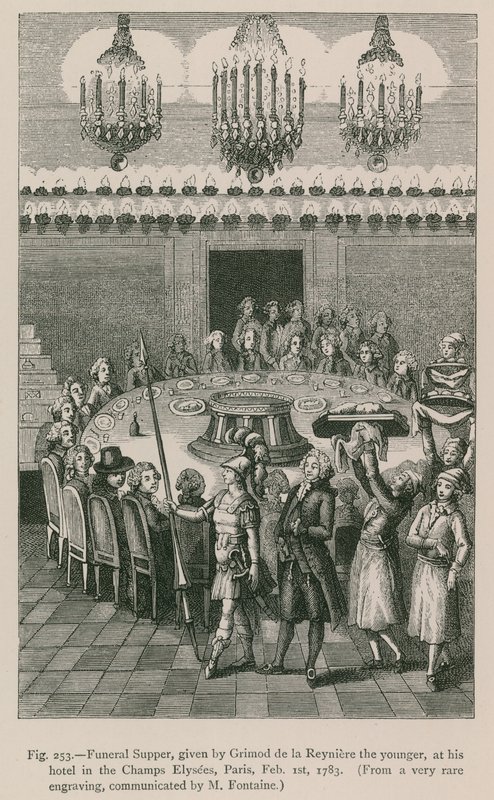

Grimod famously sent out invitations to his funeral, which would take place that very day, at the usual time of the evening meal. His friends must have been shocked, both at the lateness of the notice and at the time chosen. Some friends came; many did not. Those that arrived found a hearse waiting outside, in the entrance was a coffin draped in black. As they gathered and waited, doors to the inner sanctum were opened. Hundreds of candles illuminated the room, in the center a long table laden with delicacies and morsels of delicious foods, and there, at the head of the table, sat a grinning Grimod who grandly announced to his guests that dinner was served. Stunned guests were later informed that he had done it simply to determine who his real friends were.

On another occasion, at a feast designed to mock the morals of the bourgeoisie, guests shared the meal with a live pig seated at the head of the table and dressed in the finery of Grimod’s father. Only for his parents to return early and walk in on the whole debacle. This soon became a scandal amongst the chattering classes of Paris, the humiliation too much for Grimod’s parents to bear. His father obtained a “lettre de cachet” from the King and had him exiled to the Augustine abbey of Domèvre-sur-Vezouze in Lunéville, where he would remain for several years.

Whilst at the Abbey, Grimod dined with the Abbott, and it is said to be here where he studied and developed his love of fine food and the art of cooking. With the fall of the Ancien Régime, and with Paris in turmoil, he traveled to Alsace, Provence, Switzerland, and more, always pursuing a culinary education: even opening a gourmet grocery store in Lyon.

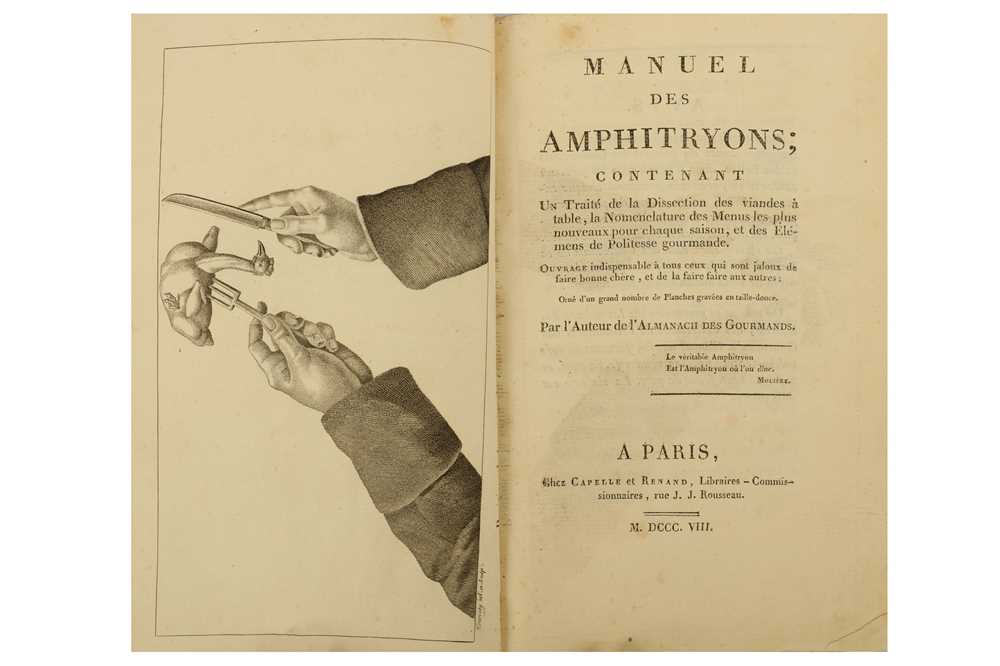

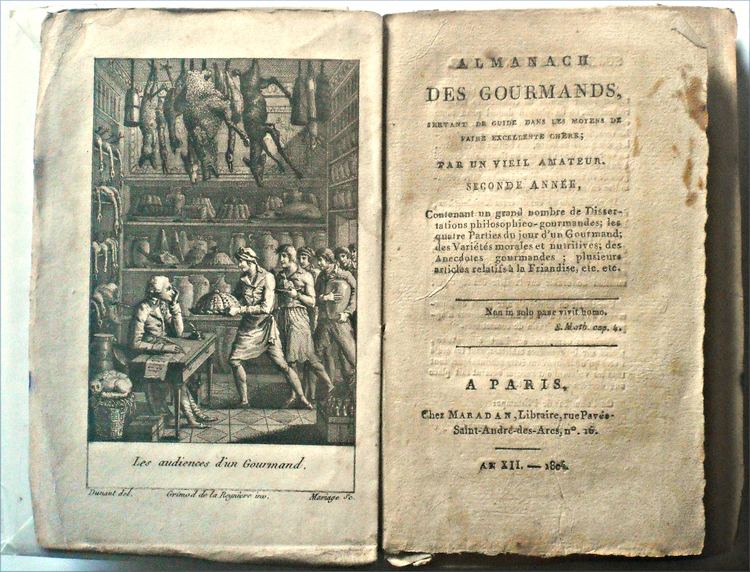

When he was finally able to return to France, he would revolutionize the way we look at food, create a whole new genre of writing and set off a career path in culinary journalism that survives and thrives to this very day.

“Grimod de La Reynière was the founder of culinary journalism. His articles in newspapers and yearbooks fed restaurants with new ideas. No more was the art of good eating a luxury reserved for the banquet halls of nobility. The one whose fingers were all over this had none: Grimod de La Reynière, grand master of pen and spoon, was born with no hands, and he wrote, cooked, and ate with hooks.”

― Eduardo Galeano, Mirrors: Stories of Almost Everyone

ACT FOUR

KAMPOT CRAB WITH COCONUT CURRY SAUCE

Kampot crab served with a coconut curry sauce, highlighting bold flavours and fragrant spices.

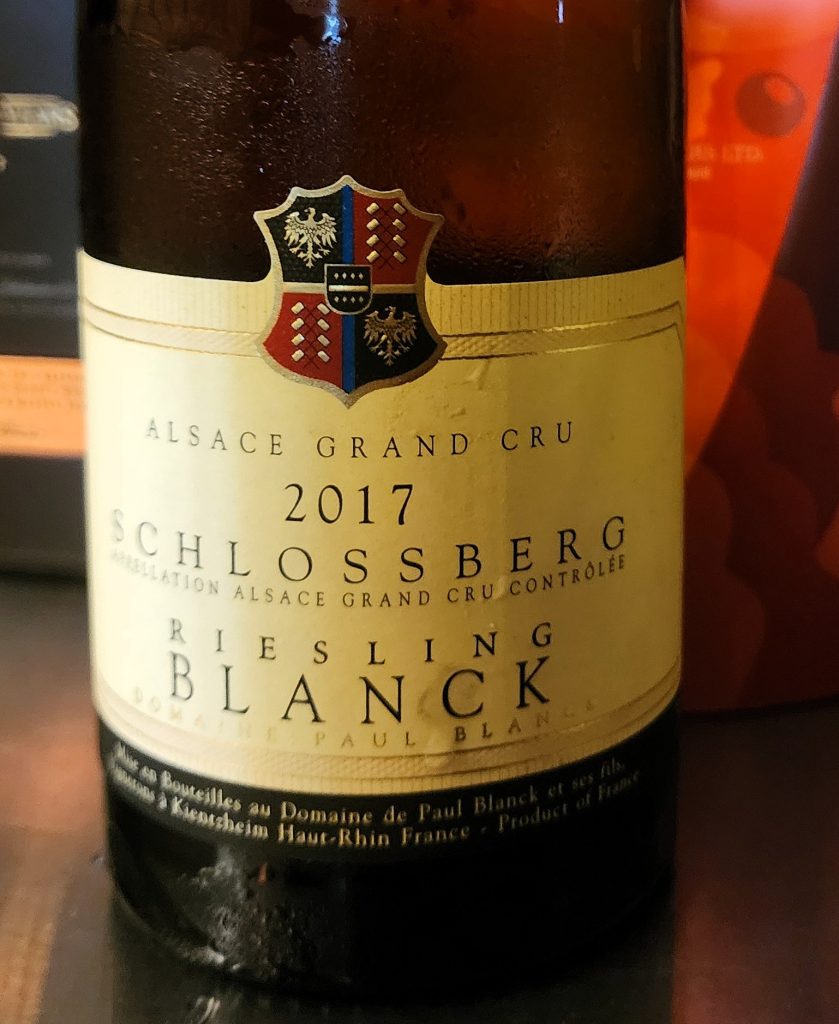

Domaine Paul Blanck, Schlossberg Riesling, GRAND CRU, Alsace France 2017

A marvellous jungle curry with good spice and a creamy coconut; it was well balanced and full of delicious flavour. Hans Blanck began acquiring vines for the family in 1610. The Blanck family then went on to play a crucial role in recognizing the potential of the Schlossberg site, which eventually led to its designation as Alsace’s first Grand Cru in 1975. The Schlossberg Grand Cru site is on a steep hillside with granite soils; it has been cultivated since at least the 13th century. This Schlossberg showed impressive varietal purity and character with freshness and citrus combined with some evolved terpene characters. A dry wine that was gorgeously slippery on entry, building to magnificent tension with the persistent mineral and chalk acidity on the finish. An exceptional Schlossberg from one of its finest producers.

Darren Gall