CRAB FEST -ACT FIVE: Guillotine Gastronomy

“The discovery of a new dish does more for the happiness of the human race than the discovery of a star.”

― Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin

Let them Eat Crab!

When he eventually returned to a post-revolution Paris, Alexandre Balthazar Laurent Grimod de La Reynière found a very different city. It was a humbling time for the young gourmand, and with his father’s passing, he needed to get his affairs in order. Grimod found himself amongst a nouveau riche, an emerging class he felt had little clue about fine arts and were completely uninformed when it came to the art of the table.

The 1789 Revolution upturned the entire social and political foundations of France; many royal chefs lost their jobs because their employers literally lost their heads! However, this would ultimately prove to be a time when French cuisine would flourish. The guild system collapsed, as part of the old regime, and chefs were now free to (or forced to) pursue their own interests. Restaurants and commercial kitchens were soon springing up all over the city and beyond. French cuisine became more accessible; the food once served in royal courts adapted and was now available to everyone via hotels, restaurants, inns, and even some homes, thanks to cookbooks becoming very popular across the country and eventually, throughout the Western world.

The Guillotine Gourmand

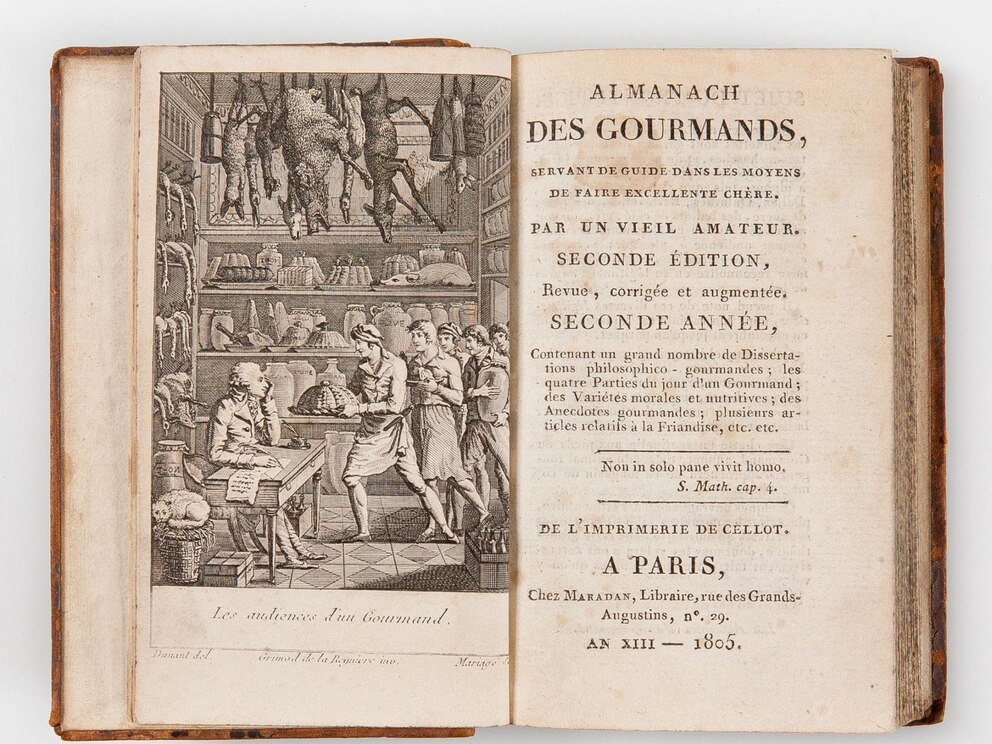

After dabbling for a while as a theatre critic, Grimod turned his attention to gastronomy and authored the ‘Almanach des Gourmands’ (from 1803 to 1812) which made him France’s first gastronomic journalist. Grimod used his vast culinary knowledge to publish tips, recipes, menus, and most importantly, reviews of restaurants’ dishes. The success of the Almanac saw the release of a monthly journal, the ‘Journal des Gourmands et des Belles’, in 1896, where he would gather with selected friends known as La société épicurienne, once each week, either at Hôtel Grimod de La Reynière or at Rocher de Cancale restaurant, where they would ‘ruminate on the gastronomy of the day’ and appraise a selection of the finest dishes sent to them by the wave of ambitious new restaurants opening in Paris.

He published his Hosts’ Manual (Manuel des amphitryons) in 1808, by now Grimod was always seen as the host and presiding culinary genius at dinner. The French literary critic Charles Augustin Sainte-Beuve called him the ‘Father of the table.”

With his sardonic, razor-sharp wit and his dark and disdainful humour, Grimod could catapult chefs to success or destroy a fledgling career even before it had started and soon had made as many enemies as admirers. Upon the death of his mother in 1812, he inherited the family fortune, married his devoted mistress, and retired to the Château de Villiers-sur-Orge, and withdrew his claws from the table. He lived until the age of seventy-nine, passing away on Christmas Day, 1837.

A final irony in Grimod’s life: the chateau he chose to purchase and live out his life was called “La Seigneurie,” which had belonged to Marie Madeleine d’Aubray, the Marquise de Brinvilliers (1630 – 1676), a name that lives on in infamy for her having murdered her father and brothers by poisoning their food with Acqua Tofana. This event sparked a series of investigations and trials that would become known as ‘The Affair of the Poisons’, a major murder scandal during the reign of King Louis XIV.

The French historian Pascal Ory noted that ‘While others at the time were focused more on art, literature, and drama, Grimod opened the door to criticism of food and cookery, inventing the gastronomic guidebook, the gastronomic treatise, and the gourmet periodical. There was literature about food and eating before Grimod, but it was concerned only with technical aspects and recipes, while Grimod introduced the idea of epicurean criticism.’ His eight volumes of ‘L’Almanach des Gourmands’ are still today a rich source of culinary knowledge and wonderful insight into the enjoyment of fine dining and French cuisine. Grimod de la Reynière was the first person to adopt a critical approach to food writing, a revolutionary stance at the time that laid the foundation for modern food criticism.

“Wine is the intellectual part of the meal, whilst meat is the material.”

-Alexandre Dumas

ACT FIVE

HONEY LIME & GINGER SORBET (PALATE CLEANSER)

A refreshing sorbet made with honey, lime, and ginger. This was a refreshing little reviver and fascinator, designed to cleanse the palate and prepare it for the aria to come.

SURF & TURF

100g cold-smoked Australian beef tenderloin, king crab leg, served with smoked mash, grilled asparagus, and roasted beets.

Gustave Lorentz, Reserve, Pinot Noir, Alsace France, 2021

Domaine Paul Blanck ‘F’ Pinot Noir, Alsace France, 2016

Alaskan King Crab: there is simply no finer crab on the planet, and this one was expertly prepared and presented. Rich, succulent, with a tantalizing hint of crystalline, deep-sea salt, this is as good as it gets. Paired with some incredible beef, cold smoked and cooked to perfection, this dish was the culinary high point of the evening.

Two wines for this course, both exceptional Alsace Pinot Noir. The Gustave Lorentz first, with classic Alsace Pinot, dry with good length through the palate, wonderful structure, acidity, and attractive fruit of cranberry and red fruits, a whiff of dried herb, a hint of ginger, pencil shavings, and some earthier tones. The wine is excellent with food and finishes with exceptionally fine, persistent tannins.

The Paul Blanck is from the Furstentum Vineyard; as an older wine, there are more evolved characters with riper, berry notes, plum, cherry, and blackberry. On the palate, there is a lovely creamy texture on entry, a nice core of red berries, and tannins that have softened a little with time. The fruit is given further complexity by accents of undergrowth, mushroom, and some leathery notes. This is a compelling Alsace Pinot Noir.

Darren Gall