Il Mangera le Riche – Révolution and Food

Il Mangera le Riche – Révolution and Food

Nothing would be more tiresome than eating and drinking if God had not made them a pleasure as well as a necessity.

Voltaire

Fête Nationale Française, (known as Bastille Day) is France’s ‘National Day’, the anniversary of the storming of the Bastille on 14 July 1789, which was a major event in the French Revolution. The occasion was first celebrated as the Fête de la Fédération, (Unity of the French People) and was held on the 14th of July 1790, it was attended by over a quarter of a million Parisians, and the feasting went on for four whole days.

The French Revolution completely changed the social and political structure of France. It put an end to the monarchy, to feudalism, and it took political power away from the Catholic church. It brought new ideas to the people of Europe including liberty and freedom for the common person. It abolished slavery and recognized the rights of women. Whilst the revolution ended with the rise of Napoleon, the ideas and reforms that it gave rise to continue to influence governments right up to this very day.

The French Revolution completely changed the social and political structure of France. It put an end to the monarchy, to feudalism, and it took political power away from the Catholic church. It brought new ideas to the people of Europe including liberty and freedom for the common person. It abolished slavery and recognized the rights of women. Whilst the revolution ended with the rise of Napoleon, the ideas and reforms that it gave rise to continue to influence governments right up to this very day.

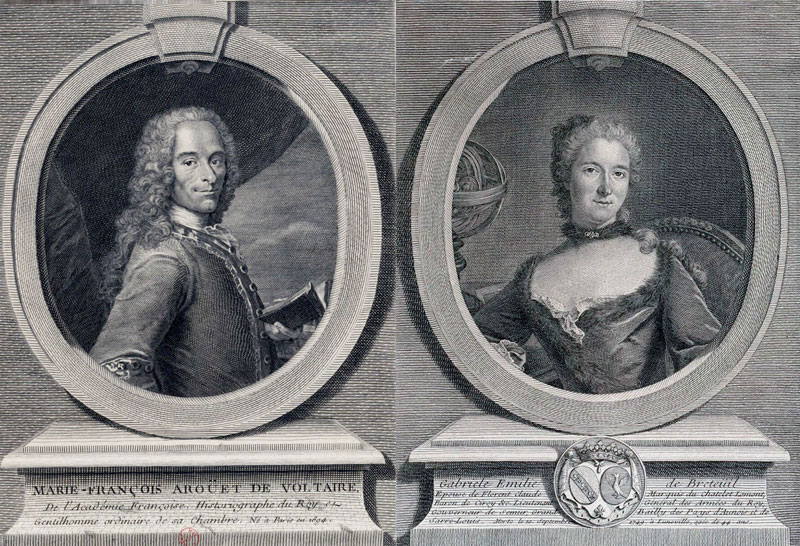

The Stain of Voltaire’s Ink

François-Marie Arouet (1694-1778), known as Voltaire, was a writer, philosopher, poet, dramatist, historian, and polemicist of the French Enlightenment. He is regarded as one of the key agitators for change that fomented unrest against the ruling classes.

Voltaire believed that through sound thought and good reason man separated himself from all other living creatures and he held in great disdain matters of faith and the corruption of power from the ruling classes. He used his pen as an epee and he wielded it with all the precision of a master swordsman in a fencing match or, as a surgeon with a lancet, performing open-heart surgery.

His reasoning was his artillery; his wit, his bon mots, and his put-downs were legendary, often humorous, he dissected his opposition, taunted them, toyed with them. Voltaire’s particular cruelty was not to merely turn the tide of popular opinion against his opponents but, to have the people laugh at them with disdain, to humiliate them, and in doing so, annihilate them. He once wrote that to hold a pen was to be at war. Few targets could ever remove the stain of Voltaire’s ink.

Voltaire was not a man of mercy, yet some would say that Voltaire had good reason to terrorize the ruling classes of France in the early 1700s. Born into a middle-class family of little importance and a young writer struggling to make his name as a man of letters, Francois Marie Arouet as he was then known was beginning to gain a reputation as a bit of an upstart; a petty pot-stirrer amongst a court society used to considering it their privilege to do and get away with whatever they damn well pleased.

Voltaire was not a man of mercy, yet some would say that Voltaire had good reason to terrorize the ruling classes of France in the early 1700s. Born into a middle-class family of little importance and a young writer struggling to make his name as a man of letters, Francois Marie Arouet as he was then known was beginning to gain a reputation as a bit of an upstart; a petty pot-stirrer amongst a court society used to considering it their privilege to do and get away with whatever they damn well pleased.

The young Arouet was an idealist who believed that rulers should be enlightened souls who protected the people’s rights and when he saw injustice he lashed out; his pen was indeed very sharp, and soon he began to deeply offend and gather serious enemies.

Voltaire was actually jailed for many a short spell in the Bastille for offending the nobility, the final straw came after he had traded insults with the aristocratic Guy Auguste de Rohan-Chabot known as the chevalier de Rohan and the Comte de Chabot.

The Chevalier organized for Voltaire to be beaten in the street like a peasant whilst he watched from the comfort of his carriage, leaving the young writer busted up and bleeding in the gutter.

Voltaire was said to be incandescent with rage and began to prepare for a duel to the death, the Rohan family meanwhile, obtained a ‘lettre de cachet’ from King Louis XV and used this warrant to force Voltaire back into the Bastille and then into exile in Great Britain.

Francois Marie Arouet would relish his time in England and appreciate the philosophical and scientific breakthroughs taking place during this pre-industrial revolution period, a time of philosophical and scientific enlightenment in England. He returned to France, and changed his name to Voltaire, still angry, still an agitator, but now very much an enlightened one, few would ever again attempt to humiliate him.

Voltaire would spend three years in exile before returning to Paris, he then made a series of very sound business partnerships that would ultimately see him gain serious wealth. In 1733 he met and fell deeply in love with Emilie du Chatelet, (1706 – 1749) a woman twelve years his junior but, with her own formidable intellect and determined individual disposition. They would spend the next sixteen years together and form one of the great romantic and intellectually influential love affairs in all history.

Emilie du Chatelet was indeed a remarkable woman and one who made several great contributions to science, she had a profound influence on Voltaire, his thinking, and his writing.

Emilie du Chatelet was indeed a remarkable woman and one who made several great contributions to science, she had a profound influence on Voltaire, his thinking, and his writing.

She was regarded as the first and only woman of science and mathematics during her time in France, she published a novel criticizing Locke, which emphasized the need for knowledge to be empirical and verified through experience.

She published a paper on heat and light, predicting what is today known as infrared radiation. She wrote a paper titled ‘Lessons in Physics’ in which she attempted to reconcile complex ideas from some of the leading thinkers of the time.

She translated Sir Isaac Newton’s ‘Principia Mathematica’ into French and then conducted experiments that were based on Gottfried Leibnitz’s theories on kinetic energy and velocity, counter to Newton’s theory. She published a critical analysis of the bible and she also translated the extraordinary poem by Bernard Manderville, (1679 – 1733) ‘The Fable of the Bees’ into French:

The poem was published in 1705, and the book in 1714. The poem suggests such key principles of economic thought, as the division of labour and the “invisible hand”, seventy years before these concepts were elucidated by Adam Smith. Two centuries later, the noted economist John Maynard Keynes, (1883 – 1946) cited Mandeville to show that it was “no new thing to ascribe the evils of unemployment to the insufficiency of the propensity to consume”, a condition also known as the paradox of thrift, which was central to Keynes theory of effective demand.

However, at the time of publication, the fable was considered scandalous. Keynes noted:

Mandeville gave great offense by this book, in which a cynical system of morality was made attractive by ingenious paradoxes.

In her preface to the translation, Emilie du Chatelet mounted a withering argument for women’s education. Chatelet also wrote a book on the nature of happiness, both in general and especially pertaining to women.

“Judge me for my own merits, or lack of them, but do not look upon me as a mere appendage to this great general or that great scholar, this star that shines at the court of France or that famed author. I am in my own right a whole person, responsible to myself alone for all that I am, all that I say, all that I do.

It may be that there are metaphysicians and philosophers whose learning is greater than mine, although I have not met them. Yet, they are but frail humans, too, and have their faults; so, when I add the sum total of my graces, I confess I am inferior to no one.”

‑Mme du Châtelet to Frederick the Great of Prussia, (1712 – 1786)

Voltaire and Emilie du Chatelet were indeed a formidable couple -one the voice of reason and the other the voice of science- questioning the old-world order in a new age of empiricism and enlightenment.

Voltaire and Emilie du Chatelet were indeed a formidable couple -one the voice of reason and the other the voice of science- questioning the old-world order in a new age of empiricism and enlightenment.

The central tenets of Voltaire’s philosophy were enlightenment, freedom of speech, freedom of the press, the right to assembly, and freedom of religion:

All of which were largely denied to the common people in France at the time. He also argued for the right to oppose and question the capricious, cruelty of absolute rule and militarism and to oppose slavery -all of which were normal practices during Voltaire’s lifetime.

Voltaire believed that with good reason, scientific analysis and with logic, and common sense, we should be able to make better decisions about life, governance, and beliefs and that rulers and monarchs should be surrounded by learned, incorruptible men, capable of free thought, to advise them, he believed strongly that this would make for a better, happier, more prosperous society as a whole. Although, later in life he seemed to abandon the idea of the enlightened monarch when he wrote at the end of his most enduring work, Candide, ‘It is up to us to cultivate our garden’.

Much of what Voltaire was arguing for at the time is taken for granted as true and correct today but, it was by no means acceptable to all of French society at the time and the outcomes of Voltaire’s debates, arguments, and writings were not assured. He was railing against the Ancien Regime which involved an unfair balance of power and distribution of taxes between the three estates of the monarchy and its nobles, the clergy, and then the commoners and middle class, who were burdened with most of the taxes and few of the benefits.

The Noble Savage

“‘When the people shall have no more to eat, they will eat the rich.”

Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Voltaire would have one legendary opponent in his lifetime and that opponent would have the name of one Jean Jacques Rousseau, (1712 – 1778) a formidable foe with romantic and somewhat wild theories for the way man should live.

Rousseau’s theories were attractive to many who felt the warring world of rulers, generals, priests, and influencers of the 1700s had lost the plot. Rousseau was advocating an entirely different solution to Voltaire and one that the French writer would find completely unpalatable.

Where Voltaire believed that through education and reason, we could separate ourselves from beasts, Rousseau argued that the way we went about these things was unnatural and corrupted us, he preached that we should get back to our natural state and live a more natural life, unconfused and at peace in the world.

Rousseau sent Voltaire a copy of his “The Social Contract” and Voltaire wrote him the following:

“I have received your new book against the human race, and thank you for it. Never was such a cleverness used in the design of making us all stupid. One longs, in reading your book, to walk on all fours. But as I have lost that habit for more than sixty years, I feel unhappily the impossibility of resuming it. Nor can I embark in search of the savages of Canada, because the maladies to which I am condemned render a European surgeon necessary to me; because war is going on in those regions; and because the example of our actions has made the savages nearly as bad as ourselves.”

Rousseau was, at least initially, influenced by the philosophies of Denis Diderot, (1713 – 1784) with whom he had spent much time reading. Diderot was a materialist, who believed in hereditary knowledge and rejected the benefit of empirical knowledge preached by Voltaire and others, Diderot felt that progress through greater physical knowledge led man on a downward spiral of corruption.

Rousseau’s philosophy did not call for humankind to return to a state of stupid beasts but, he felt that we were entering a stage of corrupted civilization and the perfect state for human beings lay somewhere back from this evil evolution. He termed this state as the ‘Noble Savage’.

Rousseau’s philosophy did not call for humankind to return to a state of stupid beasts but, he felt that we were entering a stage of corrupted civilization and the perfect state for human beings lay somewhere back from this evil evolution. He termed this state as the ‘Noble Savage’.

Against the philosophies of Hobbes, Rousseau argued that man in his basest, most natural state is essentially and instinctively good and that we must get back to this instinctive goodness that has been corrupted by reason and logic.

The heart was pure, the head wanted to lead it astray. Rousseau predicted that the more man deviated from his natural state in nature, the worse off he and his home would be. Rousseau taught that we would be free, wise, and good in the state of nature and that instinct and emotion, when not distorted by civilization, are nature’s instructions to inner peace and the good life.

Rousseau was also considered a hero, having a great influence on the French Revolution which would take place barely a decade after his death. His most revered work is, ‘The Social Contract’ (1762) which outlines a government in a classical republicanism framework, which itself evolved from the political writings of philosophers such as Aristotle, (384 BC – 322 BC) Cicero, (107 BC – 44 BC) Machiavelli, (1469 – 1527) and Montesquieu, (1689 – 1755). He was an advocate of democracy and believed in a ‘general will’ that should be enforced by an elected government for the good of all, over and above any personal or private interest.

Rousseau saw a world full of decadence and corruption and held a deeply pessimistic view for the future unless we returned to nature and a more natural way of living. It is easy to deride and criticize Rousseau, (as Voltaire did mercilessly) yet it is interesting to reconsider his views today in light of man’s negative impact on his environment and the frightening and increasingly likely implications of that impact on our future.

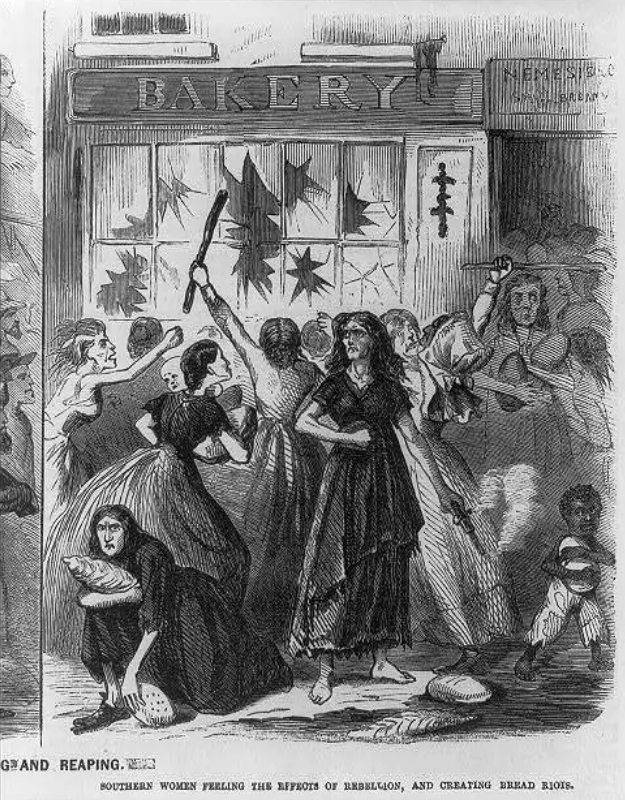

Qu’ils mangent de la brioche – The Bread Riots

Qu’ils mangent de la brioche – The Bread Riots

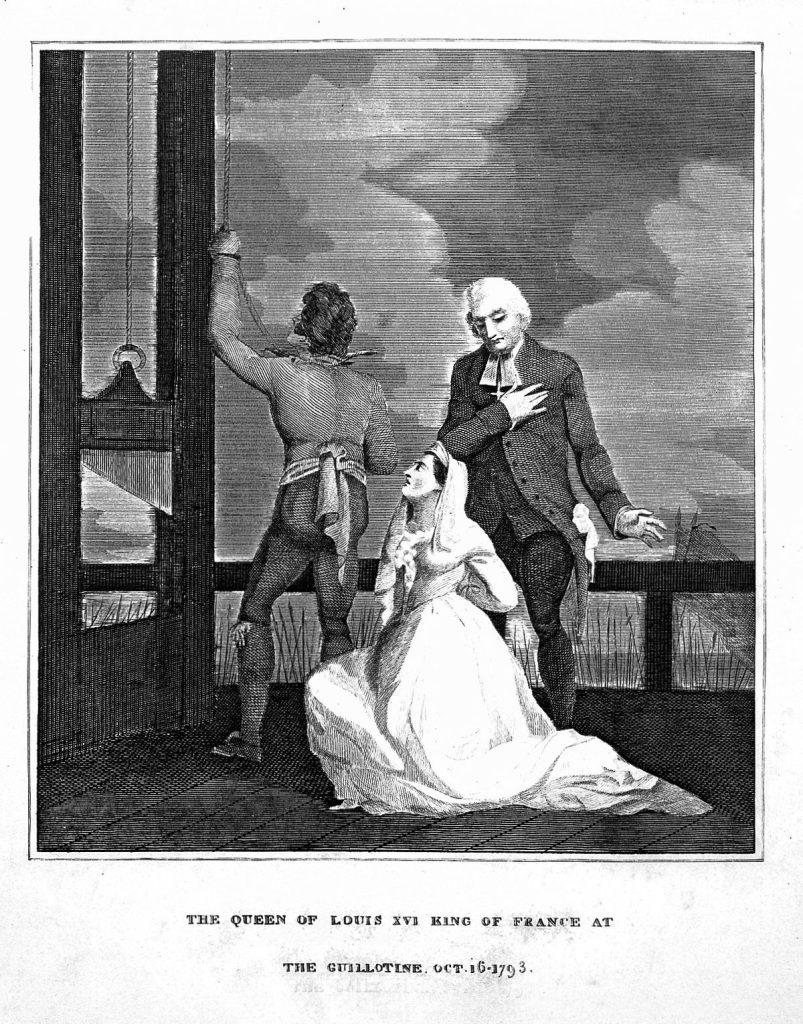

Perhaps the most widely attributed quote to Marie Antoinette, queen of France at the time, responding to the news that her subjects had no bread is the response: “Let them eat cake” (actually, brioche) is almost certainly not true. J. J. Rousseau put these callous words into the mouth of an anonymous princess in his Confessions, written in 1766 when Marie Antoinette was just ten years old and living in Austria.

Voltaire is oft-quoted for the remark that Parisians required only “the comic opera and white bread”, and whilst the many reasons behind the revolution were both complex and complicated; a shortage of grain to make bread and the resultant hyperinflation, along with a high tax on salt, further agitated the masses against the l’Ancien Regime.

Voltaire is oft-quoted for the remark that Parisians required only “the comic opera and white bread”, and whilst the many reasons behind the revolution were both complex and complicated; a shortage of grain to make bread and the resultant hyperinflation, along with a high tax on salt, further agitated the masses against the l’Ancien Regime.

‘Bread Riots’ were becoming increasingly common and the Police had to take control of all aspects of bread production, bread was now a crucial ingredient in trying to keep the peace.

Four Soups

Rice soup, Scheiber, Croutons with lettuce, Croutons unis pour Madame

Two Main Entrees

Rump of beef with cabbage, Loin of veal on the spit

Sixteen Entrees

Spanish pates, Grilled mutton cutlets, Rabbits on the skewer, Fowl wings a la marechale, Turkey giblets in consomme, Larded breasts of mutton with chicory, Fried turkey a la ravigote, Sweetbreads en papillot, Calves’ heads sauce pointue, Chickens a la tartare, Spitted sucking pig, Caux fowl with consomme, Rouen duckling with orange, Fowl fillets en casserole with rice, Cold chicken, Chicken blanquette with cucumber

Four Hors D’Oeuvre

Fillets of rabbit, Breast of veal on the spit, Shin of veal in consommé, Cold turkey

Six dishes of roasts

Chickens, Capon fried with eggs and breadcrumbs, Leveret, Young turkey, Partridges, Rabbit

Sixteen small entremets

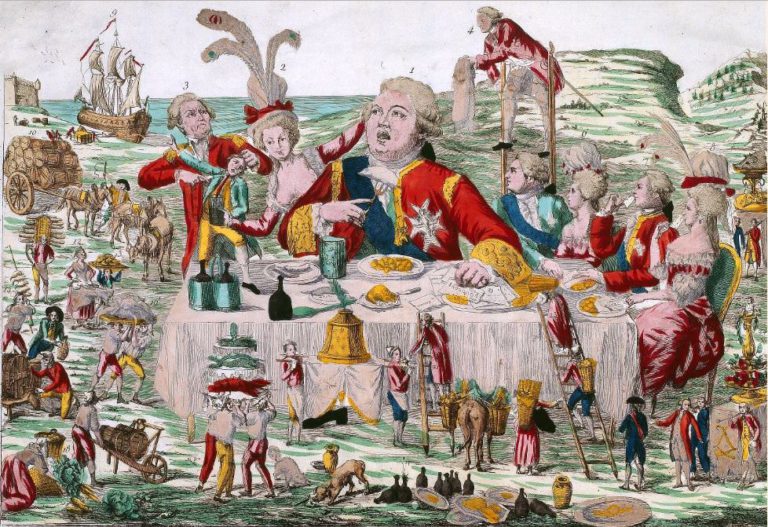

Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette would hold lavish public banquets like this one almost every single day, designed as a way of exhibiting their power and wealth. The royals had access to foods unimaginable to ordinary French people, many of whom were struggling just to feed themselves.

In 1785 France faced considerable economic difficulties, mostly concerned with unfair taxation; yet it was one of the richest and most powerful nations in all of Europe, and its people enjoyed more freedoms and justice than many of their neighbours.

However, King Louis XVI, his ministers, and the French nobility had become toxically unpopular because the peasants were burdened with ruinously high taxes, to fund the privileged classes and their ludicrously lavish lifestyles. The aristocrats were confronted by the growing ambitions of the merchants, tradesmen, and farmers, who were now aligning themselves with the aggrieved peasantry, wage-earners, and with academics and intellectuals influenced by the ideas of the Enlightenment philosophers such as Voltaire and Rousseau.

A growing number of French people had absorbed the ideas of “equality” and “freedom of the individual” as presented by the philosophers of the Enlightenment. The recent American Revolution had demonstrated to them that the Enlightenment’s ideas about good governance could realistically be put into practice.

A growing number of French people had absorbed the ideas of “equality” and “freedom of the individual” as presented by the philosophers of the Enlightenment. The recent American Revolution had demonstrated to them that the Enlightenment’s ideas about good governance could realistically be put into practice. Viva la Evolucion!

Viva la Evolucion!

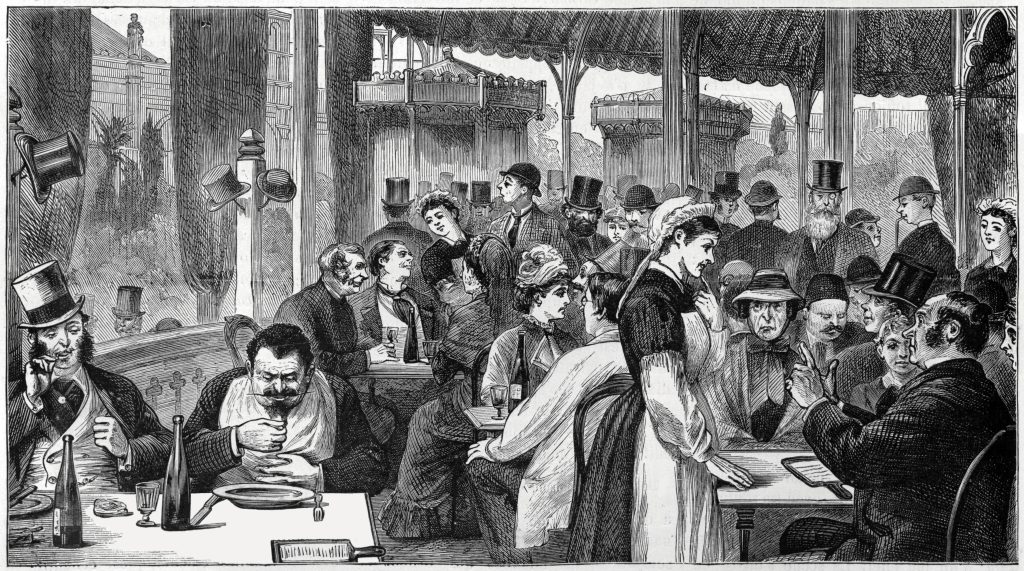

Before the revolution the French economy had been tightly controlled by guilds, and it was difficult to become a merchant or a craftsman, (such as a baker). However, after the revolution, the guilds were decimated and it became easier for anyone to enter these professions. The ruling class of the old regime has lost their wealth, (and many of their heads) and they no longer had the capacity to employ artisans and chefs.

This meant that many craftsmen found themselves out of work and yet also free to pursue other opportunities. Many were forced to extreme measures and resorted to opening their own places of hospitality to attract customers to come and dine. This was the birth of French fine dining and the restaurant scene as we know it today.