Kuy Teav: A Morning Ritual in a Bowl of Phnom Penh Noodles

As the first light of dawn touches the confluence of the Tonle Sap and Mekong rivers, Phnom Penh stirs to the sound of metal ladles clinking against ceramic bowls and the rhythmic thwack of a cleaver against a wooden block. This is the soundtrack of kuy teav, Cambodia’s definitive breakfast, its soul in a bowl.

To the uninitiated, it might look like just another noodle soup in a region defined by them. But to a Cambodian, kuy teav is a liquid map of history, resilience, and the delicate balance of the Khmer palate.

The Anatomy of the Broth

The heart of any great kuy teav stall—identifiable by the towering glass cabinets filled with pre-blanched noodles and hanging cuts of meat—is the cauldron. Unlike its Vietnamese cousin, Pho, which leans heavily into charred ginger and star anise, a Khmer broth is a masterclass in clean, pork and marine-inflected depth, intensity and irresistible moreishness.

Pork bones are simmered for hours, but the “secret sauce” lies in the addition of dried squid and earthy radishes. This creates a base that is light yet profound, a shimmering gold liquid that anchors the dish.

A Texture of Resilience

The noodles themselves, made from local rice flour, are thin and elastic. They are flash-boiled to a perfect al dente—or as locals might say, just enough “snap”—before being dressed in a signature garnish: toasted garlic oil. This oil is the soul of the dish, providing a fragrant, nutty crunch that cuts through oils and fats in the dish.

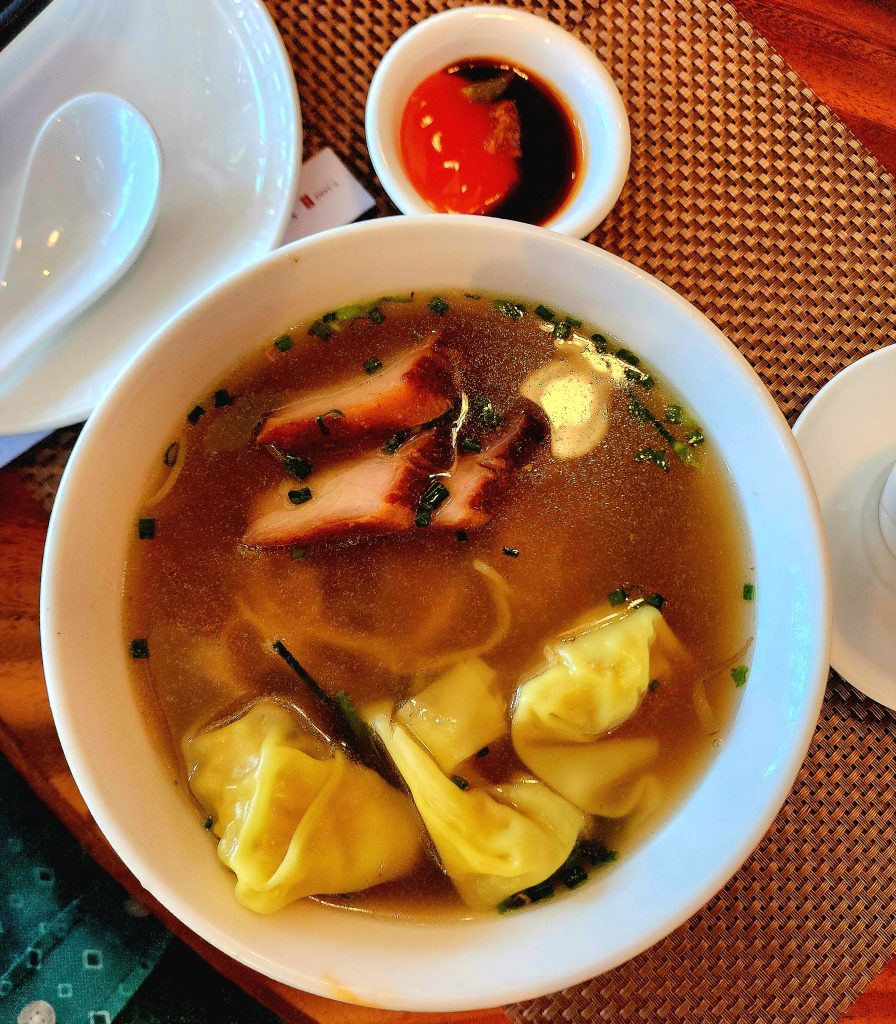

A standard bowl is a crowded, joyous affair:

- The Proteins: Slices of pork loin, minced pork, and often “the works”—liver, heart, or blood cubes.

- The Crunch: Fresh bean sprouts, garlic chives, and the essential squeeze of lime.

- The Kick: A dollop of fermented chilli paste or a splash of pickled green chillies.

More Than a Meal

There is a specific sociology to the kuy teav stall. In the morning, the plastic stools of a street-side vendor are the great equalisers of Cambodian society. You will see a high-ranking official in a crisp white shirt sitting elbow-to-elbow with a tuk tuk driver, both hunched over their bowls, steam swirling about their faces.

While “Phnom Penh Noodle Soup” (kuy teav Phnom Penh) has gained international fame, the dish is a testament to the Chinese-Southeast Asian fusion that has defined the region’s culinary evolution over centuries. It is a dish that survived the darkness of the 1970s, preserved in the memories of those in the diaspora and revived with fervour in the kitchens of the modern Kingdom by chefs like Luu Meng.

As the tropical sun begins to bite at 8 am, the last of the broth is ladled out. The stall owner wipes down the stainless steel, the ritual complete. To eat kuy teav is to consume the energy of this place —vibrant, complex, and deeply life-affirming.

Many people swear by the power of their mom’s chicken soup to cure all manner of maladies, from a common cold to a broken heart. However, the healing properties of kuy teav transcend old wives’ tales and urban legends about magical chickens.

About eight years ago, an amoeba took up residence in my liver; the damned thing almost killed me. For three weeks, I had to visit the Naga clinic at 7 am every morning to see Dr Galena, a 70-odd-year-old lady doctor who had a wiry and spritely build, a sparkle in her eyes and a smile that matched her demeanour, pure mischief.

Dr Galena came from Eastern Europe, lived at the old Bulgarian Embassy and told me she’d spent twenty years practising medicine in Africa, before spending the next twenty in Asia. She would usually be out in the car park when I arrived, puffing on her umpteenth cigarette of the morning! I came to cherish this irascible, eccentric lady a great deal, loved her like a caring aunt; the truth is, she saved my life.

Every morning, once I had finished with the needles and drips, I would head to the nearest Yi Sang in Boeung Keng Kang 1 and order a large steaming bowl of kuy teav noodles with roast duck, or char siu pork and dumplings. I’d ladle in the chilli and dark sauce, the green chilli, a handful of bean sprouts, Chinese chives, and begin the soul-restoring gulping and slurping that became my morning ritual, watching and listening to the city wake up and come to life; in a way, it helped save my life too.

Almost a decade later, and I still perform this morning ritual with my seven-year-old son, and it is something I intend to do with my four-month-old son as soon as he is old enough.

You see, people don’t just eat noodles for breakfast here, a village, a community, a city comes together over it, the whispers of their stories, their livelihoods and their culture floating in the steam, that is why it is called Phnom Penh noodles, it is like no other, it is the flavour of this place.

Darren Gall