Happy Birthday Sophie

I am sitting in a wine bar in Phnom Penh’s Old Quarter, enjoying lunch with Sophie Solnicki, the commercial director of Clos Fourtet, savouring some of her magnificent wines. It is noon on the 12th November 2025, and Sophie is in a joyous mood; tomorrow is her birthday.

I, on the other hand, am rattled. I do not really have time for this, deadlines are closing in, I received the invitation late, but it is Sophie and it is Clos Fourtet, and it is with my good friend Vibol. I decided to attend, of course, and so here I am in a den of thieves, a place that housed the country’s most infamous art thief, stealing lunch. However, no laws will be broken here today; it is all legitimate and outrageously magnificent.

The Crown Jewels

Just a couple of weeks before, on October 19th, thieves disguised as construction workers had stolen eight pieces of the French Crown Jewels from the Galerie d’Apollon of the Louvre in Paris. It was global news and made for topical small talk, as the wines breathed in air and the room exhaled and relaxed.

The Ministry of Culture identified the stolen items as:

The tiara, necklace, and an earring from the sapphire set of Queen Marie-Amalie and Queen Hortense.

The emerald necklace and a pair of emerald earrings from the Empress Marie Louise set.

The reliquary brooch, a large corsage bow brooch and the tiara of Empress Eugénie de Montijo.

The prosecutor said that “the Louvre curator estimated the damages to be €88 million” but added that “the greater loss was to France’s historical heritage”.

Breathtaking in its audacity and amount, and yet, this was not the first precious theft from France’s most famous art museum, nor was it the most sensational.

The Crime That Shocked the World

On the morning of 21 August 1911, Louvre employee Vincenzo Peruggia—an Italian handyman and glazier who had previously worked installing protective glass on museum artworks—slipped into the Salon Carré. The museum was closed for cleaning.

The Mona Lisa, which hung nearly unnoticed among dozens of other Renaissance paintings, was lightly guarded and not yet regarded as the world’s most famous artwork.

Peruggia simply lifted the painting from the wall, carried it to a stairwell, removed it from its frame, concealed it under his coat, and walked out.

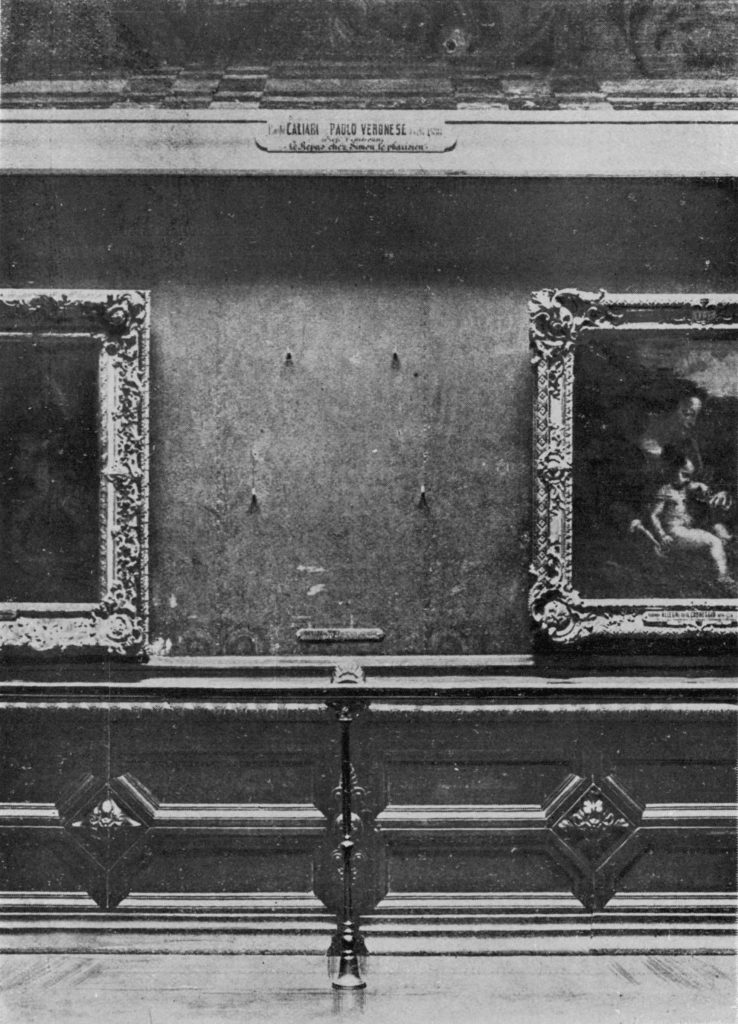

It took over 24 hours for anyone to notice. A painter who came to study Leonardo’s sfumato found an empty space where the portrait should have been. Chaos erupted. Museum officials shut the building. The police scoured the premises. Paris newspapers proclaimed the theft an international catastrophe.

The Mona Lisa had vanished.

“Good artists copy, Great artists steal.”

-Pablo Picasso

The “affaire des statuettes”

The Paris-Journal newspaper had offered a reward as well as the promise of anonymity to the thief if they would return La Gioconda (the Mona Lisa). On August 29, one week after the theft, a most unusual letter arrived on the editor’s desk. It was to be the first of several.

“It was in March 1907, that I entered the Louvre for the first time—a young man with time to kill and no money to spend … I suddenly realised how easy it would be to … take away almost any object of moderate size.”

The letter spoke of another theft at the Louvre, a small sculpture of the head of a woman, which the thief had sold to a ‘painter-friend’ for fifty francs. The letter went on to describe how the thief would then go to visit the museum several more times and was able to make a steady income for himself. Security was lax, and the thefts, it seems, were easy. In the end, the letter was a sort of lament that the Mona Lisa theft would see a sharp increase in better security and an end to this lucrative career.

The Letter did not arrive alone, with it a small statue that was later proven to be missing from the Louvre. The paper identified the author as simply ‘The Thief.’

In the coming days, more letters arrived, and this time they were signed by a ‘Baron Ignace d’Ormesan.’

Prefect Lepine quickly identified the Baron, a fictional character from a collection of stories written by the poet Guillaume Apollinaire. Just a few days after the Mona Lisa’s disappearance, Apollinaire had also written to L’Intransigeant, just days after the heist.

“The pictures, even the smallest, are not padlocked on the walls, as they are in most museums abroad. Furthermore, it is a fact that the guards have never been drilled in how to rescue the pictures in case of fire. The situation is one of carelessness, negligence, and indifference.”

Police were soon knocking at the poet’s door.

La Bande de Picasso

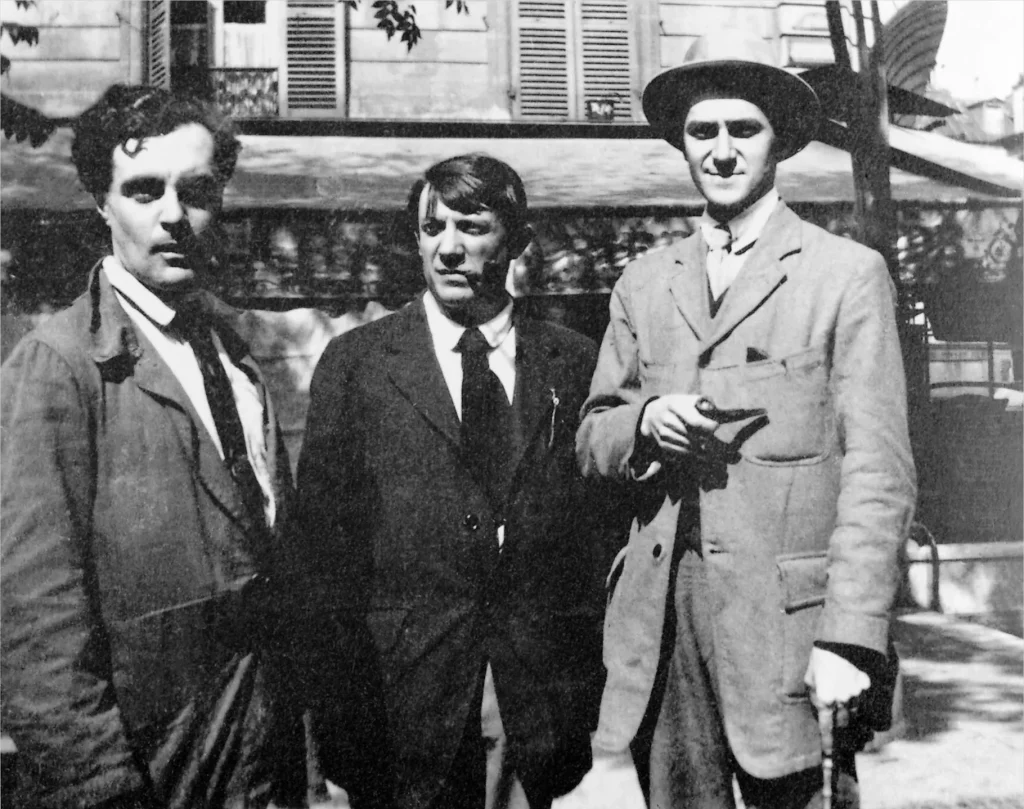

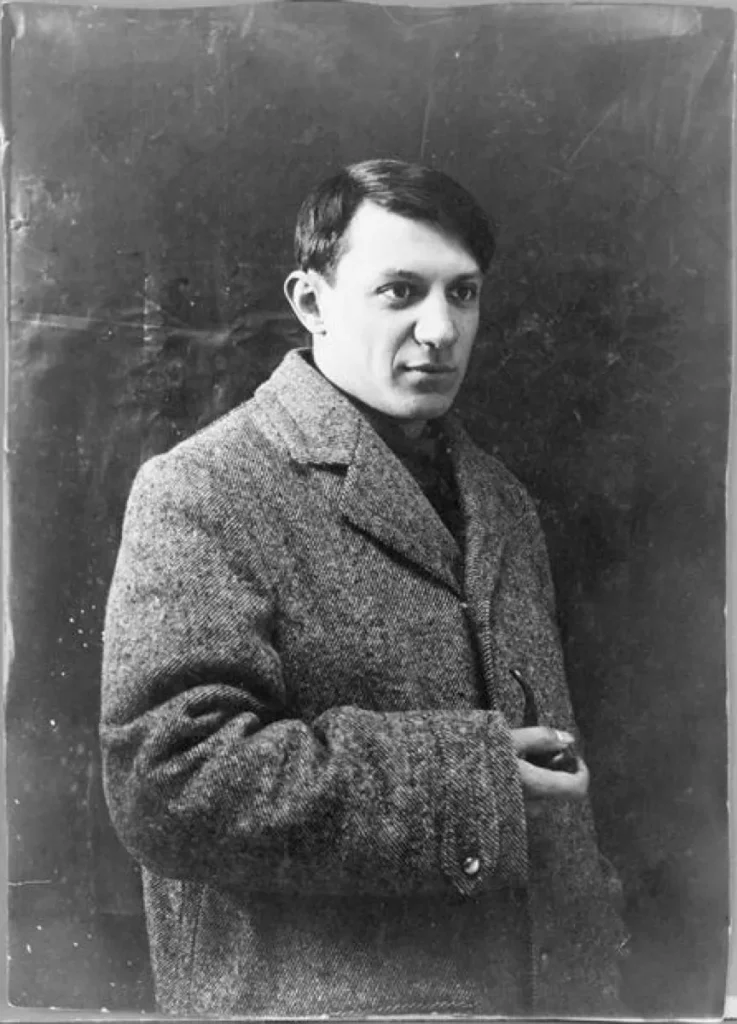

Apollinaire was a part of ‘la bande de Picasso,’ a group of avant-garde, bohemian artists as famous for their loud opinions as for their art. They were considered outlaws of traditional art, seeking to break all the rules to free it from its own history. The Mona Lisa could be considered a symbol of everything this crowd rejected about art; for them to be involved would not come as a surprise to anyone.

Prefect Lepine was certain of it, and Apollinaire’s letters as the Baron placed him in deep peril.

The Betrayal

Apollinaire and his friend Picasso were terrified; both had stolen statues purchased from Pieret, and drastic action was needed. The two friends stuffed the statues into an old suitcase and, in the dead of night, lugged the evidence on foot to the banks of the Seine. They then discovered that neither could bring themselves to toss these rare artifacts into the river.

In the morning, Picasso sent the statues to the Paris-Journal anonymously.

Guillaume Apollinaire was soon transported in handcuffs to the Palais de Justice. Confronted with arrest, he gave up Pieret, who had been living in his apartment as a secretary.

He admitted being aware of Géry’s theft, informing Lepine that he had offered him a train ticket to Marseilles, and urged him to leave the country. Apollinaire was promptly locked in a cell at Le Santé prison.

La bande de Picasso was the guilty party, Prefect Lepine knew it. He was confident they would crack under pressure and would soon be telling him of the Mona Lisa’s whereabouts.

Lepine went straight after Picasso himself.

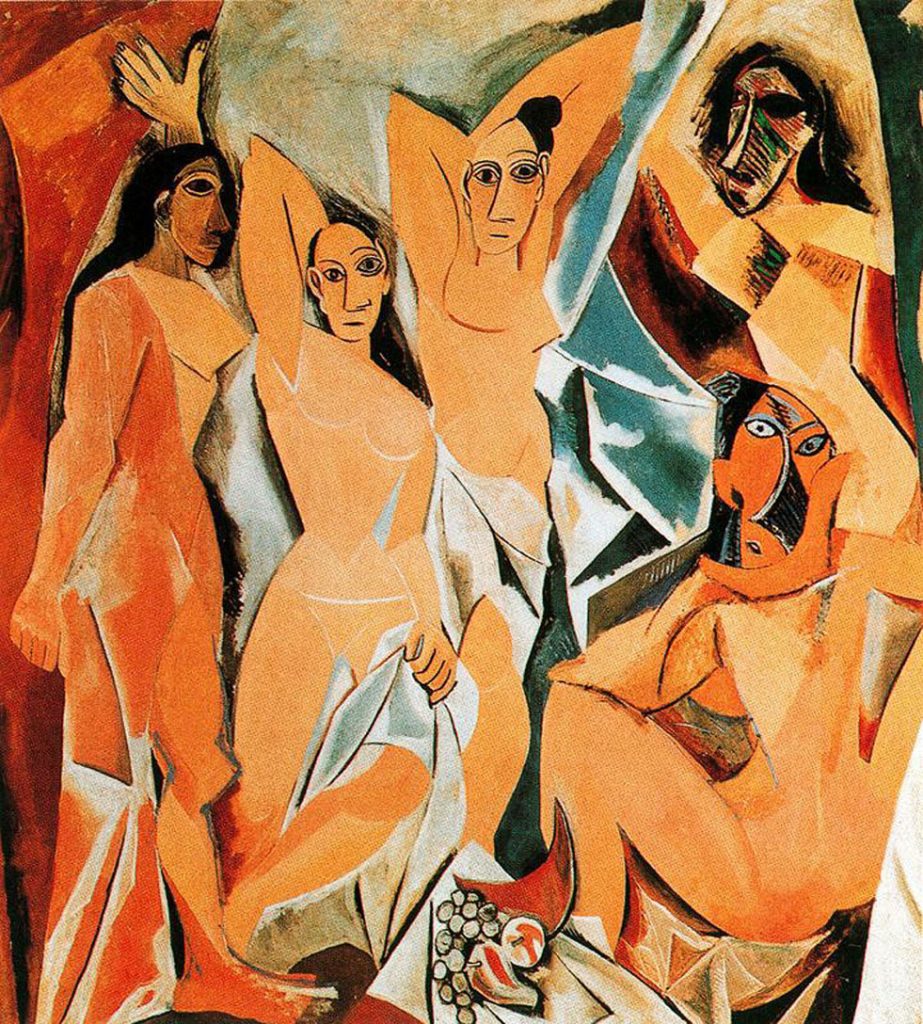

Picasso admitted to having purchased two stolen statues from Pieret, having been implicated by his panicked friend Guillaume Apollinaire. They had even influenced his famous work, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon.

However, in court, they were nervous and frightened; they contradicted each other, misspoke, seemed unsure, and confused. When asked about his friendship with Apollinaire, Picasso said, “I have never seen him before.”

Picasso would not speak of this incident for decades. When he finally did, in 1959, he said, “When the judge asked me, ‘Do you know this gentleman?’ I was suddenly terribly frightened, and without knowing what I was saying, I answered, ‘I have never seen this man.’ I saw Guillaume’s expression change.

The blood ebbed from his face. I am still ashamed.”

A Dead End

Picasso was released on his own recognisance, with a warning not to leave Paris. Apollinaire was returned to prison, but without enough evidence, was soon released.

The trial was a farce. Apollinaire confessed to everything surrounding the stolen statues and, of course, knew nothing about the stolen Mona Lisa. Picasso wept hysterically and somewhat shockingly in court. Overwhelmed by testimony that was both conflicting and illogical, presiding Judge Henri Drioux felt he had little choice but to dismiss the case, ultimately releasing both men after issuing a stern warning.

Louis Jean-Baptiste Lépine had previously been the Governor General of Algeria and would twice be the Prefect of Police with the Paris Prefecture. He reformed the police force, and some of his forensic methods and training were celebrated and copied around the world. Yet here in 1911, Lepine’s line of inquiry had reached a dead end.

Today, many art historians speculate that Picasso was not merely in possession of stolen goods but may have commissioned the robbery and even participated in it himself!

The image of the modernist prodigy, flustered and frightened, denying involvement in the disappearance of the Mona Lisa, became part of the surreal mythology of the affair. Newspapers took delight in juxtaposing the “wild young modernists” with the refined Renaissance portrait. The scandal cemented Picasso and Apollinaire as members of the artistic avant-garde while revealing how deeply the theft tapped into cultural anxieties about modernism, nationalism, and the sanctity of art.

Meanwhile, the real thief of the Mona Lisa went unnoticed.

La Giaconda’s Dramatic Return

For two years, the Mona Lisa remained missing. The truth was astonishingly simple.

Peruggia had stolen the painting out of a misguided sense of patriotism. Convinced that the French had stolen the Mona Lisa from Italy, he planned to “return” it to Florence and become a national hero. (In reality, Leonardo himself had transported the painting to France, where it had been acquired legally centuries earlier.)

In late 1913, Peruggia attempted to sell the painting to an Italian art dealer in Florence. Instead of buying it, the dealer contacted the authorities. Peruggia was arrested, and the Mona Lisa toured Italy triumphantly before being returned to the Louvre under a blaze of publicity.

Ironically, the theft achieved what centuries of hanging quietly on a museum wall had not: it transformed Mona Lisa into a global icon.

The Birth of a Modern Celebrity Artwork

Before 1911, the Mona Lisa was admired, especially among artists, but it was not considered the world’s most famous painting. The theft changed that forever.

Newspapers around the world carried photographs of the space (now empty) where the painting belonged on the wall. Updates circulated daily. Worldwide interest in the crime made the portrait a symbol of mystery, beauty, vulnerability, and cultural significance.

The episode also triggered major reforms in museum security across Europe. The Louvre strengthened its protection of key works, installed enhanced surveillance, and adopted new display standards.

A Theft That Changed the World

The 1911 theft of the Mona Lisa was far more than a sensational crime. It was a turning point in the cultural history of the modern world—propelling a Renaissance painting into global superstardom, entangling artistic giants like Picasso in the drama, and influencing how future cultural leaders like the French Minister for Cultural Affairs, André Malraux, framed the nation’s role in safeguarding art.

“There is always a need for intoxication: China has opium, Islam has hashish, the West has woman.”

― André Malraux

The First Ladies

Jacqueline Kennedy, the First Lady, wife of American President John F. Kennedy, had a degree in French literature, and first met Andre Malraux during the Kennedys’ state visit to France in 1961.

Malraux escorted the First Lady through Paris’s sites, while her husband attended meetings with President Charles de Gaulle. The French public was charmed by the First Lady’s perfect French and her thorough knowledge of the country’s history.

Galerie Magazine noted that it was apparent even to President Kennedy that he had been upstaged by his beautiful, sophisticated wife when he exclaimed, “I am the man who accompanied Jacqueline Kennedy to Paris!”

The First Lady is quoted as saying that Malraux was “the most fascinating man I’ve ever talked to”.

In 1962, the Kennedys held a dinner at the White House in Malraux’s honour, inviting prominent American artists and writers to highlight the importance of the arts and culture in the White House. It has been written that “Perhaps no other White House dinner had more personal meaning for Jacqueline Kennedy than the evening honouring French Minister of Culture André Malraux at the White House on May 11, 1962.”

By now, Malraux was totally smitten by Mrs Kennedy, whilst to the First Lady (according to her social secretary, Letitia Baldrige), Malraux had become Mrs. Kennedy’s most important cultural mentor; she listened to him, wrote to him, and considered him her “prize”.

Jacqueline Kennedy was by now cultivating a plan; hers was a dream that would take all her guile, charm, and diplomatic powers of persuasion to make come true.

So it was, that at the dinner at the White House, held in his honour, she politely asked Malraux if it would be possible to loan the Mona Lisa to the United States. By the end of the evening, Malraux is said to have whispered a promise to the First Lady that he would do everything in his power to send La Giaconda to her, France’s most famous cultural treasure.

La Giaconda Abroad

She was shipped in a custom, temperature-controlled, fireproof container. French stipulations ensured the temperature would not fluctuate by more than one degree. The ship received extensive security, including a U.S. Coast Guard escort into New York Harbour and protection from local, state, and federal officials. The painting was then transferred to an armoured, air-conditioned van, accompanied by a large motorcade that included local, state, and federal security officials, including the Secret Service. Its route to the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. was cleared of all traffic, with the motorcade travelled at high speed with lights and sirens blaring.

The painting was kept under constant watch by security guards during its stay.

The Mona Lisa was in America in December 1962 and departed in March 1963. Over 1.6 million people visited her during her visit. This included a special, private viewing for President Kennedy and dignitaries, followed by public exhibitions at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, where approximately seven hundred thousand people came to see her. Before she was transported to The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, where it is estimated that over one million people came to meet her.

Today, millions visit the Louvre each year to glimpse the painting that once vanished. Its fame, paradoxically, is owed not only to Leonardo da Vinci’s genius but also to the extraordinary moment when it disappeared—and the world realised how much it mattered.

Jilted

Malraux was enchanted by the First Lady and dedicated his memoirs, published in 1967, to her. However, the nature of their relationship changed after President Kennedy’s assassination in 1963. Mrs. Kennedy eventually re-married in October 1968.

According to reports from the time, Malraux was deeply disappointed by her re-marriage and, as a result, ordered the removal of Jacqueline Kennedy’s dedication from all subsequent printings of his book, and they never spoke again.

“Art is the lie that enables us to realise the truth.”

-Pablo Picasso

Malraux & Picasso

The relationship between Pablo Picasso and André Malraux was a fascinating intersection of artistic genius and political/literary power. Their mutual admiration and occasional deep interactions fundamentally shaped the cultural narrative of the 20th century.

Malraux, the celebrated novelist, intellectual, and later France’s Minister of Culture, was one of the most articulate and influential interpreters of Picasso’s work. His writings, particularly in The Voices of Silence, placed Picasso among the great masters who fundamentally changed the language of art. Malraux’s intellectual framework legitimised Picasso’s revolutionary genius for a wider global audience, focusing on the artist’s ability to transcend cultural and historical boundaries.

Picasso, for his part, offered Malraux profound insights into his own artistic mind. One of the most famous documented conversations is Picasso’s 1937 account to Malraux of his transformative visit to the Trocadéro Ethnographic Museum.

Malraux, as Minister of Culture, played a key role in celebrating the artist, notably organizing the massive “Tribute to Picasso” exhibition at the Grand and Petit Palais in 1966. Their bond was about a shared, elevated vision of the power of art to challenge destiny.

“Chanel, General De Gaulle and Picasso are the three most important figures of our time”.

-Andre Malraux

La Tête d’Obsidienne

Malraux’s 1974 book, titled Picasso’s Mask (originally La Tête d’Obsidienne, or The Obsidian Head), is not a formal biography but a personal memoir and philosophical meditation on the artist and the meaning of his work.

The book was written following Picasso’s death in 1973, when Malraux was summoned by Picasso’s widow, Jacqueline Picasso, to the artist’s final home in Mougins, France.

Here, Malraux was surrounded by Picasso’s last, most visceral paintings (often described as “painted face-to-face with death”) and the artist’s immense personal art collection. It was in this overwhelming environment that Mrs Picasso asked Malraux to write the book.

The book is an affectionate memoir based on Malraux’s long personal acquaintance and conversations with Picasso. A profound analysis of Picasso’s genius and the metamorphosis of his art across his many styles and periods. It is a detailed commentary on much of Picasso’s work, often rooted in Malraux’s own memories of seeing them.

The title symbolises the artist’s public, often rebellious, persona (the mask) versus the private man and the driving, almost magical force of his genius. Malraux connects Picasso’s work to the primitive, spiritual power of art. The book is an evocative, memory-filled prose that stands as one of the most profound intellectual tributes to the towering figure of Pablo Picasso.

“All art is a revolt against man’s fate.”

-Andre Malraux

MuMa

The André Malraux Museum of Modern Art—known simply as MuMa—stands as one of France’s most remarkable cultural institutions, both for the breadth of its collection and for its embodiment of André Malraux’s visionary ideas about art, museums, and the democratisation of culture. Situated on the waterfront of Le Havre, the museum is a radiant, glass-and-steel structure that symbolises a modern, open, and accessible approach to artistic heritage.

A Museum Born of Renewal and Modernity

Le Havre suffered enormous devastation during World War II, and its post-war reconstruction -supervised by the architect Auguste Perret- became a landmark of modern urban planning. Within this context of rebirth, the decision to establish a major art museum was both symbolic and strategic. The original museum opened in 1845 but was destroyed during the war; its post-war reinvention sought not simply to replace what was lost, but to embrace a vision of modernity.

The current building, inaugurated in 1961, is a masterpiece of minimalist, light-filled architecture. Its designers—Guy Lagneau, Raymond Audigier, and Jean Prouvé, with assistance from artist Henri Matisse—created one of the first French museums built entirely in glass and steel. This transparent, airy structure was revolutionary, inviting natural light to illuminate the artworks and reflecting the maritime landscape around it.

Named in Honour of a Cultural Revolutionary

In 1999, the museum was renamed after André Malraux, France’s first Minister of Cultural Affairs (1959–1969). Malraux revolutionised France’s approach to cultural policy. He championed the idea of bringing art to the widest possible audience, advocating for what he famously called the “museum without walls”—a world where art transcends physical and social barriers.

Naming the museum after Malraux honoured his belief that art should not be confined to elite spaces but should belong to everyone. MuMa’s open, luminous architecture and its seaside setting perfectly embody his ideals of accessibility, openness, and dialogue between art and environment.

“Culture is the sum of all the forms of art, of love, and of thought, which, in the course of centuries, have enabled man to be less enslaved.”

-Andre Malraux

A Living Vision of Art for All

Today, the André Malraux Museum remains a testament to the enduring power of Malraux’s cultural philosophy. Its transparent architecture dissolves the boundary between the museum and the world; its collections highlight the evolution of modern vision; and its educational programs fulfil Malraux’s mission to democratize access to art.

MuMa is not merely a repository of masterpieces—it is a living embodiment of France’s belief that art must shine outward, like the sea-reflected light that fills its galleries, reaching all who seek it.

The Missing Laundresses

Blanchisseuses Souffrant Des Dents is an oil painting by the artist Edgar Degas. It was created around 1870-1872. This small oil on canvas depicts two women, faces turned towards each other, their gaze downward. One of the figures is holding the other’s chin as if to help ease some pain. It has been interpreted as a portrait of two washerwomen, one suffering from a toothache.

Once owned by a fellow soldier of Degas during the Franco-Prussian War of 1870, the painting was bequeathed to the State in 1953. Two days after its inauguration in 1961, André Malraux (as the Minister for Cultural Affairs) loaned the painting to the Museum of Modern Art at Le Havre. The Degas was the first government-owned painting placed in the museum,

In December 1973, the painting went missing; there were few clues as to the culprits or of its possible whereabouts.

There would be no trace of the Laundresses for another thirty-seven years.

Dirty Laundry

In December 2010, an employee of Muma was flicking through a Sotheby’s auction catalogue for their upcoming Impressionist & Modern-Day Art sale. There, incredibly, in the pages of items up for auction, was a listing of the long-lost painting.

The employee immediately called the museum’s director, who then contacted the French police and the Ministry of Culture. Sotheby’s were alerted immediately and withdrew the piece from auction. They claimed to have had no knowledge that it was stolen, nor did the seller, a New York orthopaedic surgeon and art collector named Ronald Grelsamer.

Grelsamer said he received it from his father as a gift. There have been no statements as to where or from whom his father might have got the painting.

The catalogue stated that the 6.25-inch-by-8.5-inch piece has an estimated value of $350,000 to $450,000.

Andre Malraux, who passed away in 1976, never saw the painting again for the rest of his lifetime; it was returned to France and finally made its way back to Muma in 2011.

“Man is not what he thinks he is, he is what he hides.”

― André Malraux

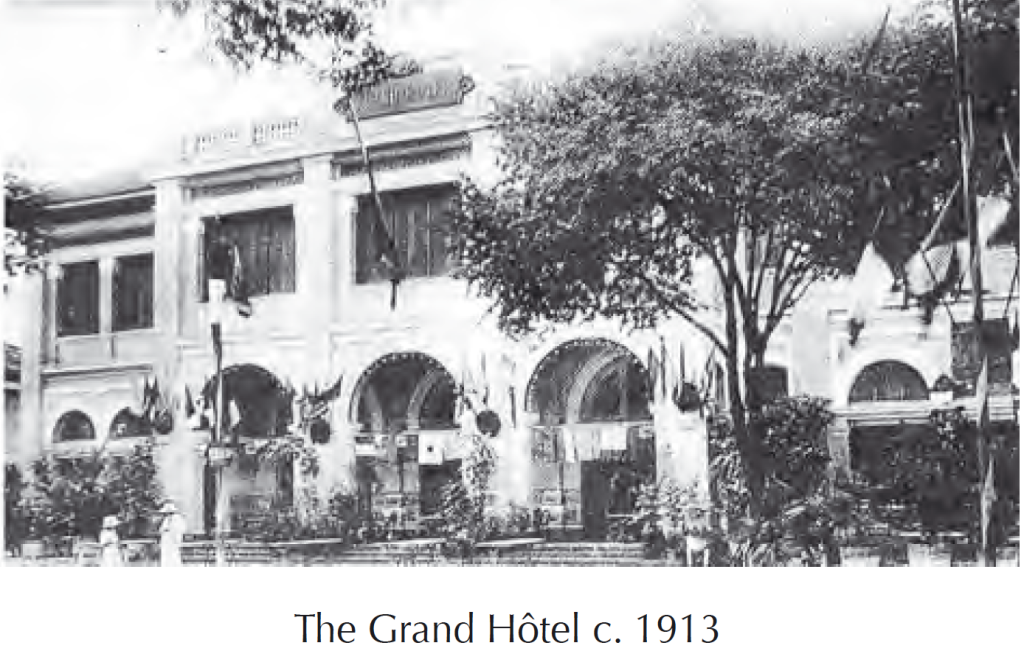

Le Grand Hotel

The Grand Old Hotel is in the old French Quarter of Phnom Penh, opposite the post office and boarded by the original Banque d’Indochine, and the French police station (commissariat), built in 1892. The Hotel building was completed sometime in the mid-1890s.

This French administrative district was built around a central square and given the name “Place de la Poste”. According to French colonial directives, the hotel’s key role was to offer accommodations that met “European standards” for visiting officials and travellers. Early documentation indicates it was first called the “Grand Hotel” and received subsidies from the French protectorate to guarantee room reservations for official purposes.

In 1918, the building was purchased by Nicolas K. Manolis, a Greek entrepreneur and well-known figure in the region. The establishment was renamed the Grand Hotel Manolis and expanded back from its river-frontage to encompass the entire block facing Post Office Square. By the 1920s, it was considered the finest and indeed the only luxury hotel in the city.

Soon, the hotel would be housing its most famous and, to some, most notorious guest, Andre Malraux.

The Malraux Affair

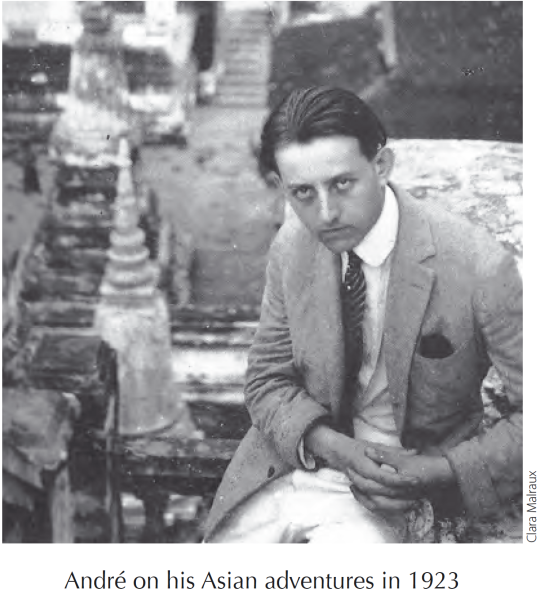

Down and out in Phnom Penh, Georges André Malraux, renowned intellectual, novelist, a member of the French Resistance, celebrated art theorist, and Charles de Gaulle’s first French Minister of Culture, was anything but the champion of great art for which he would later be celebrated.

In 1923, at the age of twenty-two, the young Malraux, along with his wife Clara, was placed under house arrest, detained at Le Grand Manolis hotel.

Malraux, as a young man, was fascinated by the exploits of T. E. Lawrence, then better known as Lawrence of Arabia. Malraux saw him as an archaeologist, an intellectual who, when called upon, became a man of action during the Arab revolt of WWI. To Malraux, Lawrence was a sort of Nietzschean hero, an adventurer, a role model, and he soon determined to abandon the Surrealist literary scene in Paris for adventure in the Far East.

Andre and Clara had been married less than a year when they lost what money they had on a bad investment in a Mexican silver mine. André came up with an idea to ‘tomb raid’ Cambodian temples and sell the artifacts on the antiquities market. He researched in libraries where he learned of the recently discovered Banteay Srey temple ruins, remote and still largely unknown outside of archaeological circles, its exquisite pink sandstone carvings had already begun attracting attention from collectors as well as colonial scholars.

Malraux soon hatched a plan.

An Archaeological Expedition

Despite the better judgments of some and perhaps due to the apathy of others, Malraux managed to obtain documentation from the Colonial Office that elevated his journey to one of an official archaeological mission.

Malraux, Clara, and schoolboy friend Louis Chevasson set sail from Marseille in October 1923, aboard the conspicuously named steamship, the Angkor. They visited Saigon and Hanoi, where they were availed with the information that removing any relics from the temples in Siem Reap was illegal, whether the temple had already been discovered or not.

They took a riverboat up the Tonle Sap bearing wooden trunks labelled ‘chemicals’ to transport, firstly the tools required, and then their ill-got gains. They hired oxcarts in Siem Reap and slashed their way with machete, out to the temple. Once there, they used their tools to remove seven slabs of stone carved with the celestial beings of apsara and devata.

The chests were transported back to Siem Reap by cart and then loaded aboard a boat for the trip back to Phnom Penh.

George Groslier was a French painter, writer, historian, archaeologist, ethnologist, architect, photographer, and curator, who studied, described, popularised, and worked to preserve the arts, culture, and history of the Khmer Empire of Cambodia. Born in Phnom Penh to a French civil servant, he is credited as the first French child ever born in Cambodia.

When Groslier, now director of the Albert Sarraut Museum (the National Museum) in Phnom Penh, met Malraux, he quickly became deeply suspicious and doubted his intentions. Groslier alerted an official in Siem Reap named Cremazy, who kept a close eye on the group once they had arrived and had their expedition to the remote temple shadowed.

Cremazy quickly reported the theft back to his commanders, who, along with the police, were then waiting for the riverboat when it reached Kompong Chhnang. The three thieves were then placed under house arrest at the Grand Hôtel Manolis. They were allowed out during the day, but they could not leave the city, it was Christmas Day.

House Arrest

The couple spent their days reading hotel newspapers and books from the National Bibliothèque. Clara contracted dengue fever and received correspondence from her mother, who begged her to end her marriage to Malraux. By the spring of 1924, they had run out of money and owed the hotel for three months’ rent. It was clear that one of them would have to get back to France and seek funds for their defence.

Clara would write in her memoir, Le Bruit de nos pas, “Our room with whitewashed walls was large, furnished with an expansive bed enveloped in its mosquito net and with a round table of dirty wood; it was one of the better rooms in the best hotel of Phnom Penh.”

Death in the Afternoon

Andre Malraux found Clara collapsed on the floor, an empty bottle of sleeping pills nearby. In a panic, he screamed for help and Clara was quickly taken to the hospital. André was able to move into his wife’s ward free of charge.

The attempted suicide was fake, and it failed to see Clara released; so, she went on a hunger strike, losing a frightening amount of weight. Eventually, whether due to her condition or the presumption that Clara was just a faithful wife following her husband, the charges against her were dropped. She had been three months in the Grand Hotel and three months in the hospital.

The plan was for Clara to return to France, sell their Picasso and raise funds for her husband’s defence. She would be on her way home when Andre’s trial began.

The Little Thief

On July 21, Judge Jodin sentenced Andre Malreaux, as the ringleader to three years in prison, Chevasson was sentenced to eighteen months. They would now be sent to the appellate court in Saigon. Malraux would finally leave the Grand Hôtel, but in some way he would always remain a part of its history and the history of this city. France would keep the stolen sculptures.

In France, Clara received the backing of illustrious literary and artistic figures, including the writers André Gide and André Maurois, who wrote articles and signed petitions in support of Malraux. In October, the appellate court in Saigon imposed a one-year sentence for Malraux and then suspended it.

André Malraux was furious, insisting on his innocence; to his mind, the temple he had looted was not officially listed as protected and therefore little more than an abandoned and ruined building. He also argued that what he had done was little more than what the governors and officials of the colony had been doing since the French arrived. Indeed, the Musée Guimet in Paris was full of such artifacts, ‘collected’ from Indochine.

Andre could not accept a guilty verdict, and so, upon his return to France, submitted an appeal. The Supreme Court of Appeal in Paris overturned the verdict on a technicality and returned the case to the Saigon court, where it apparently was never retried.

None of the expedition members would ever spend a single day in jail for their crime.

George Groslier was much less forgiving; he had witnessed cultural theft on a grand scale, and he detested Malraux and others of his ilk, contemptuously calling him ‘Le Petit Voleur,’ the little thief.

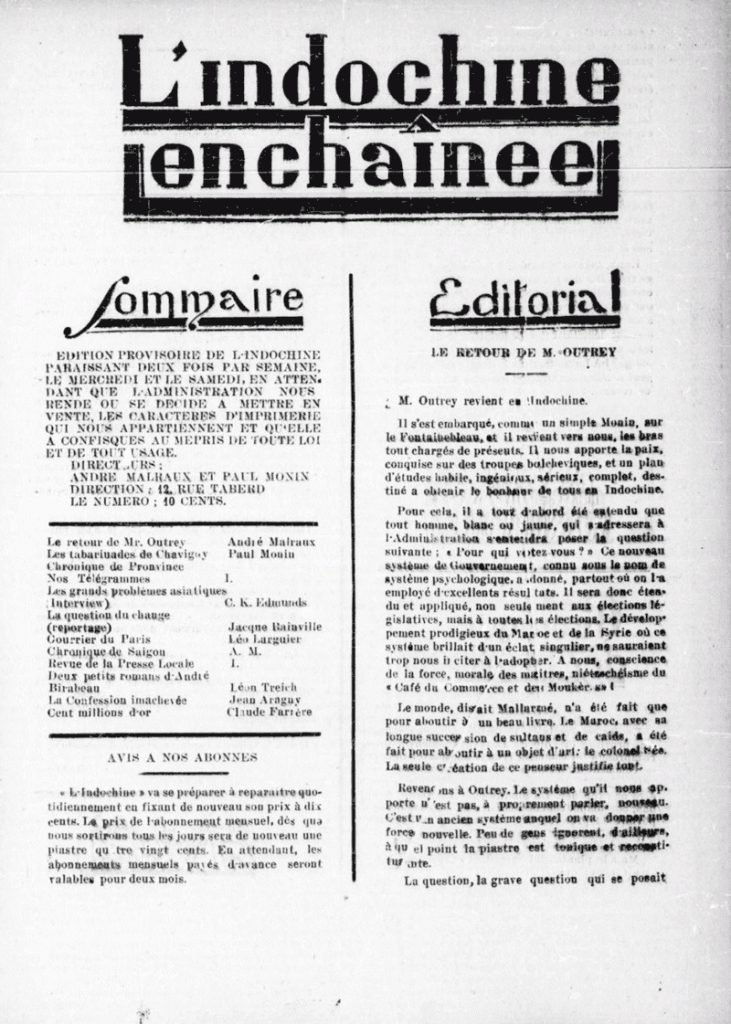

L’Indochine Enchaînée

Malraux’s twenty-six months in Indochina, the arrest and trial, had left him a deeply changed man; it radicalised him, turning him into a fervent anti-colonialist. He co-founded the newspaper “Indochina in Chains” (L’Indochine Enchaînée) in Saigon, using it as a voice to expose colonial corruption and injustice. His time in Southeast Asia would also later shape his acclaimed novels, including (the semi-autobiographical) ‘The Royal Way,’ and the Goncourt Prize-winning ‘Man’s Estate.’

For the rest of his life, Malraux never apologised, nor did he ever express any regret about the attempted theft of the artifacts.

The Weeping Woman

The city of my birth, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, prides itself as a cultural capital. A town that holds dear to its heart and celebrates deeply, the diversity, inclusiveness and sweeping sophistication of its arts and culture.

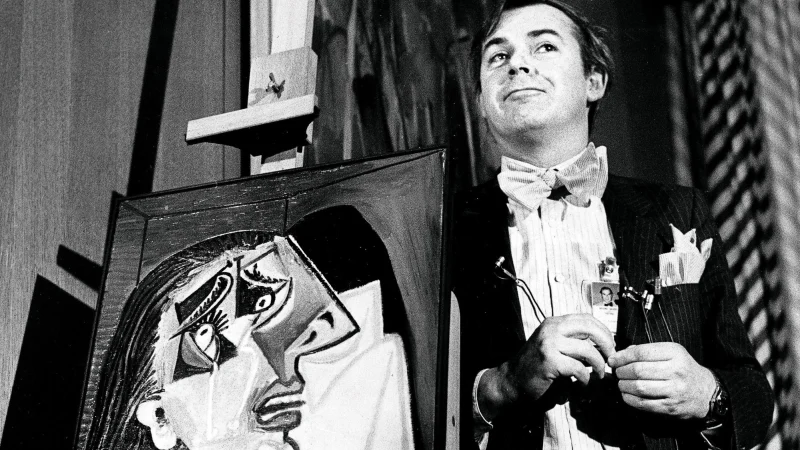

In December 1985, the National Gallery of Victoria (NGV) purchased ‘The Weeping Woman’, an oil on canvas painted by Pablo Picasso in late 1937. The painting depicts a weeping Dora Maar, Picasso’s mistress and muse. The work is part of a series produced by Picasso in response to the bombing of Guernica by Hitler’s Condor Legion and Mussolini’s Aviazzione Legionaria. It is closely associated with the iconography in his masterwork, ‘Guernica.’

The gallery purchased the painting for AUD $1.6 million, a staggering amount of money, which made it the most expensive work of art ever purchased by an Australian gallery at the time. With a falling dollar, the amount paid ended up being closer to AUD$2 million, and this far surpassed the AUD$1.3 million paid by the Australian Federal Government a dozen years earlier for Jackson Pollock’s ‘Blue Poles’. Nor was it insured, with those in power considering the cost of insurance for such major works of art as “prohibitive”.

The purchase was met with a great deal of public criticism and outcry, with many questioning the value and benefits to the city of such an expensive and unsettling artwork. The flamboyant National Gallery of Victoria Director Patrick McCaughey famously predicted the painting would “haunt Melbourne for the next 100 years.”

A.C.T.

On Saturday, 2 August 1986, just after closing, thieves unscrewed the Picasso from the wall and simply walked out of the gallery with it. The thieves left on the wall where the painting had stood a calling card.

The card indicated that the painting had been removed for routine maintenance and was signed the ACT. It has been suggested that because nobody, at any point, considered a theft, most people who saw the card believed ACT to stand for the Australian Capital Territory, the seat of Federal Government.

It was therefore, not until a ransom note turned up three days later, that anybody realised the Picasso had actually been stolen!

A Community Divided

The Melbourne arts community and the cultural milieu were deeply divided at this time, with an underground arts scene that was edgy and rebellious, up against traditional arts establishments and institutions they felt were out of touch with artists on the ground (sound familiar).

This could be encapsulated by the view that, whilst there was a distinct lack of funding for young artists in Australia at the time, there was enough money in the pot to acquire breathtakingly expensive, international acquisitions from a bygone era.

Minister for the Arts and the Plod

Race Mathews (1935 – 2025), was an Australian politician who served as a member for parliament and for both the Victorian and the Australian governments from 1972 to 1992. Throughout much of the 1980s, and at the time of the Picasso theft, he was a Minister with an unlikely dual portfolio, being the Minister for the Arts and the Minister for Police and Emergency Services at the same time. Meaning he had responsibilities in both acquiring the painting and now in recovering it.

The ransom letters were anything but polite, and they would be addressed directly to Race Matthews.

The first ransom note was received on 5th August 1986 by the Melbourne ‘The Age’ newspaper and was addressed to Race Matthews as Rank.

ATTENTION: RANK MATHEWS (MLA)

We have stolen the Picasso from the National Gallery as a protest against the niggardly funding of the fine arts in this hick State and against the clumsy, unimaginative stupidity of the administration and distribution of that funding.

Two conditions must be publicly agreed upon if the painting is to be returned.

1. The Minister must announce a commitment to increasing the funding of the arts by 10% in real terms over the next three years, and must agree to appoint an independent committee to enquire into the mechanics of the funding of the arts with a view to releasing money from its administration and making it available to artists.

2. The Minister must announce a new annual prize for painting open to artists under thirty years of age. Five prizes of $5000 are to be awarded. A fund is to be established to ensure that the real value of the prizes is maintained each year. The prize is to be called The Picasso Ransom.

Because the Minister of the Arts is also Minister of the Plod, we are allowing him a sporting seven days in which to try to have us arrested while he deliberates. There will be no negotiation. At the end of seven days, if our demands have not been met, the painting will be destroyed, and our campaign will continue.

Your very humble servants,

Australian Cultural Terrorists

A second ransom note was sent to the Melbourne Herald newspaper on the 10th August 1986

Dear, oh dear. Race Mathews, you tiresome old bag of swamp gas…

1. We have not dumped the painting in a blue-nosed funk. What should have caused us to panic? Perhaps you imagine that the news that Interpol has been alerted will cause us to cower in our ill lit garrots awaiting the inevitable knock on the door as the relentless Clouseaux of a hundred nations stalk us. What an imaginative fellow you turned out to be. Interpol! Call on Red Adair to read your gas meter, do you?

2. We hope you enjoy playing the political he-man, unflinchingly refusing the outrageous demands of these cultural crackpots. You continue flexing your political pectorals before an admiring electorate for as long as you can, Minister. Seven days after the painting came into our hands (Sat 2nd Aug. 10.00PM) if our demands have not been met you will begin the long process of carrying about you the smell of kerosene and burning canvas. You are gambling the State’s two-million-dollar investment in the Picasso industry against our twenty-cent investment in Bryant & May. Mind you, we do find your Conan the Barbarian routine terribly diverting.

3. The people of Australia, and you as one of their elected representatives, should rejoice that a theft involving less risk than shoplifting cotton hankies from David Jones was performed by a group whose first desire is to return the painting. Not that we would really expect such a sensible reaction from someone so determined to have others shoulder the blame. The responsibility is entirely yours. Good luck with your huffing and puffing, Minister, you pompous fathead. We remain,

Your very humble servants,

Australian Cultural Terrorists

A Philistine Nation

The Victorian government refused to accept any of the demands and offered a A$50,000 reward for information leading to the capture of the perpetrators. Mathews was reported as saying: “I can’t imagine that anybody who had genuinely at heart the interests either of art or of art lovers could have perpetrated an action of this sort. McCaughey was reported to have said, “We live in a philistine nation but a civilised city.”

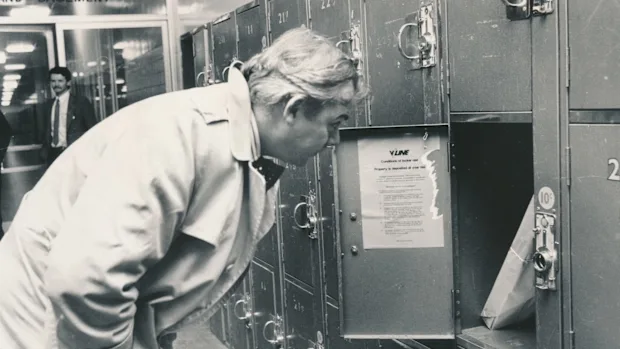

In his 2003 memoir, The Bright Shapes and the True Names, McCaughey recalled that before the painting was found, a Melbourne art dealer told him a young artist might have information. On 17th of August, at the young artist’s studio, McCaughey made it clear several times, that he sought only the painting’s return rather than pressing charges, suggesting it could be left at Spencer Street station or Tullamarine Airport as a safe means of returning it for the thieves.

Locker 227

On 19 August 1986, following an anonymous phone call to the police, the painting was found undamaged and carefully wrapped in brown paper tied with string in locker number 227 at Spencer Street railway station.

The locker was opened with a station master key. Police stated that the painting was packed in such a way as to ensure that it would not be damaged, suggesting someone in the art world or on the fringes of the art world was involved. McCaughey himself later formally identified the painting.

There was a third letter from the Australian Cultural Terrorists found in Locker 227 along with the painting. In part, it read, “Of course, we never looked to have our demands met … Our intention was always to bring to public attention the plight of a group which lacks any of the legitimate means of blackmailing governments.”

In January 1989, the case of the Weeping Woman was closed. Police said that no further investigations would be made into the theft until solid evidence was presented that any persons, including gallery staff, were involved. The case has never been solved.

The painting was returned to the National Gallery of Victoria and is now a part of its permanent collection. It was valued by Sotheby’s ten years ago as being worth over AUD$100 million.

The Fall of Empire

The Japanese arrived in Phnom Penh in 1941, garrisoning 8,000 soldiers in the capital. By 1945, they had left. Cambodia gained its independence from France on November 9, 1953, and embarked on an ambitious period of modernisation and redevelopment.

Innovative government buildings and monuments under the guidance of the brilliant Cambodian architect Vann Molyvann were rapidly reshaping the city. Over the next couple of decades, colonial-era architecture was largely neglected and began to fall into disrepair.

The horror of the Khmer Rouge era was devastating for the people of Cambodia. Phnom Penh was emptied and fell silent, a city of ghosts. Eventually, the population gradually returned, and the building that was ‘The Grand Hotel Manolis’ became the humble abode of as many as thirty desperate and impoverished families. By the end of the century, the place was little more than a ruin and a slum.

Colonial Chic

Today, a corner of the original building has been restored to something of its former glory, certainly with a respectful nod to nostalgia and all the charm and character of the French colonial era.

Le Manolis Wine Bar is a captivating bar-a-vin come bistro, with an exceptional and eclectic French wine list, serving high-quality, classic French cuisine. The décor is Art Deco and deconstructed, colonial chic, with authenticity and personality.

The same owners have also created the very colonial-chic pizzeria Cin Cin on another corner of the building, complete with wicker chairs and spritzers on the terrace.

It is a splendid venue, breathing new life into an Old Quarter fringed by the riverfront out back, the Phnom temple a block away out front and the grittier shades of the city at its edges.

The long wooden table and highchairs in the wine room create the perfect atmosphere for a good, long wine lunch, and the lineup for today promised something spectacular.

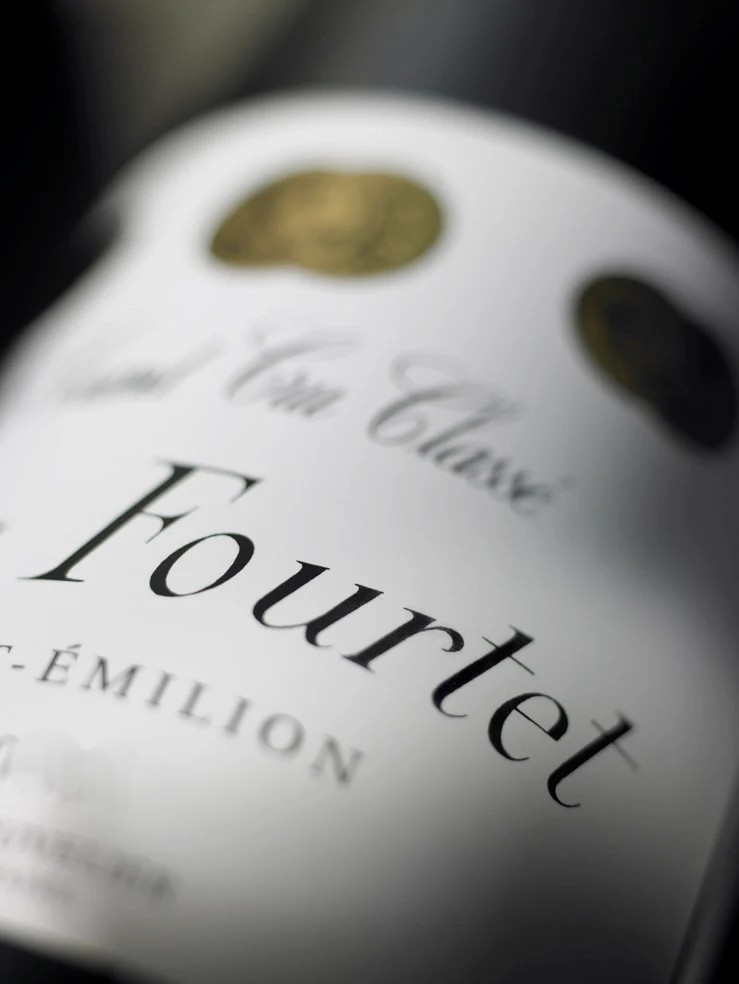

Clos Fourtet

The 1er Grand Cru Classe property, Clos Fourtet is located just outside the UNESCO World Heritage town of St. Emilion. The estate has been part of the eminent circle of Premiers Grands Crus of Saint-Émilion since the appellation’s classification began in 1954. The Chateau was originally a fort, erected during the Hundred Years’ War, but by the 1800s was already recognised for the quality of its wines.

The Chateau collected prestigious gold medals for its wines at the Paris World Fairs of 1867, 1900, along with another from the International Exhibition in Bordeaux in 1895. These medals are still proudly displayed on the Clos Fourtet front label.

Leon Rulleau planted vineyards on the site in the middle of the seventeen hundreds, and the property remained with the family until 1868. In 1919, the property was purchased by Fernand Ginestet, the founder of the negociant house Maison Ginestet and one of the greatest chateau owners and wine merchants in Bordeaux’s history.

In 1949, Fernand’s son Pierre sold Clos Fourtet to the Lurton family to facilitate the acquisition of Chateau Margaux. With Pierre Lurton as winemaker, the quality and reputation of Clos Fourtet began to improve significantly.

Pierre Lurton later became the winemaker at Cheval Blanc, whilst ownership of the estate passed to Phillipe Cuvelier in 2001. Phillipe would also purchase Chateau Poujeaux in the Moulis region in 2008 and acquire three more vineyards in St. Emilion: Chateau Les Grandes Murailles, Clos St. Martin, and Chateau Cote de Baleau. From the 2022 vintage onward, the vines from Les Grandes Murailles have been included in Clos Fourtet.

All of the family’s vineyards are now managed by Matthieu Cuvelier, and the wines made by Daniel Alard, under the esteemed guidance of consultants Stéphane Derenoncourt and Jean-Claude Berrouet (renowned for his work at Chateau Petrus).

The terroir at Clos Fourtet is one of the most prestigious in all Saint Emilion; the vines are on the famous limestone plateau that gives the wines their exceptional minerality. The vineyard covers approximately twenty-two hectares, planted to Merlot 85%, Cabernet Franc 7%, and Cabernet Sauvignon 8%. Beneath the estate, there is a vast, 13-hectare network of ancient, limestone quarries, caves and tunnels that have been converted into cellars for storage and maturation.

The wines of Clos Fourtet are some of the most attractive, well-balanced, and exceptional in the region, with all the class, poise, and finesse of a piece of fine art.

Stealing Lunch

The Menu

The lunch started with La Planche du Manolis, literally a plank of Coppa, Parma, and Serrano hams, with three exquisite cheeses.

This was followed by a veritable butcher’s block to share, including a large, tender, perfectly cooked Pork Chop, beaming from its copper dish. Glistening, succulent lamb cutlets, and a flank steak with a particularly good sear, cooked deliciously rare; it was juicy, tender, and flavourful.

The space, the mood, the company, the wines, and the food were all truly exceptional. Lunch was transporting, time no longer mattered, this was unforgettable.

The Wines

Chateau Poujeaux, Moulis en Medoc, 2017

Chateau Cote de Baleau, Saint Emilion Grand Cru, 2022

La Closerie de Fourtet, Saint Emilion Grand Cru, 2019

Clos Fourtet, Saint Emilion, 1er Grand Cru Classe, 2015

Chateau Poujeaux, Moulis en Medoc, 2017

Chateau Poujeaux’ vineyards go all the way back to the 16th Century when they were owned by the same owner (then), of Chateau Latour in Pauillac, one Gaston De L’Isle.

Owned by the Cuvelier family, the sixty-eight hectares of gravel-based soils are planted to Cabernet Sauvignon 47%, Merlot 41%, Petit Verdot 9%, and Cabernet Franc 3%. The wine is aged in French oak for twelve months (one-third new).

Aromas are of red berries, cassis, leather, cedar, and tobacco leaf with hints of bramble and graphite.

On the palate, the wine is medium-bodied red, with a fine, dry texture, elegant tannins and primary flavours of red berries, sage, and subtle spice, restrained and attractive, the length and structure are impeccable; this is a wine that gently charms and gets more and more attractive with every swirl, sniff and sip. 90/100

Chateau Cote de Baleau, Saint Emilion Grand Cru, 2022

Chateau Cote de Baleau was founded in 1643 and was owned by the Reiffers family for many generations. Their title can be traced back to the reign of King Louis XIV when an ancestor was rewarded with the vineyard for his brave exploits as a soldier.

It was purchased by the Cuvelier family in 2013, it is now producing some exceptional quality and great value-for-money wines. The 17-hectare vineyard is planted to Merlot 70%, Cabernet Franc 20%, and Cabernet Sauvignon 10%.

Aromas offer up espresso, mulberry, violets, and graphite, attractive and inviting. The palate is medium-bodied with a core of ripe berries (mulberry, plum, cassis), wrapped in silky fine tannins and showing impressive length and chalky minerality. This is incredibly good and a real bargain. 92/100.

La Closerie de Fourtet, Saint Emilion Grand Cru, 2019

The ‘second wine’ of Clos Fourtet, this wine has a composition of Merlot 90%, and Cabernet Franc 10%.

The bouquet offers black berries, cherry, star anise, coffee grinds, and five spice.

The palate exhibits a wine slightly fruit-forward, a question of both style and a hot, ripe year, with a fine, creamy entry, attractive forest berries mid-plate and very fine, silky tannins and structure. A seductive wine from a hot year, which has typically good freshness and acidity, to go with the juicy core of ripe berry fruits. 94/100.

Clos Fourtet, Saint Emilion, 1er Grand Cru Classe, 2015

An outstanding vintage from an exceptional winery, this is an unforgettable work of art, bottled brilliance, drinking superbly at ten years young and with plenty still to come. A blend of Merlot 88%, Cabernet Sauvignon 10% and Cabernet Franc 2%, matured for 15 to 28 months in French oak (60% new).

Aromas are of blueberries, cherry, raspberry, and violets with notes of mocha, allspice, and graphite. On the palate, the wine is all about incredible poise; there is impressive ripe fruit and stunning depth, but the counterpoint is elegance and that lovely tension with the freshness and minerality that exists in Clos Fourtet like a watermark. Tannins are superfine and silky with expressive length and a heady, lingering aftertaste of superb ripe fruit. An absolute classic expression of the work of an exceptional terroir, combined with an excellent vintage, and a brilliant team of winemakers. 98/100.

Priceless

On 18 November 2025, less than a fortnight after our lunch, a magnificent work of modern art, the oil painting ‘Portrait of Elisabeth Lederer’ painted by the celebrated Austrian artist Gustav Klimt from 1914 to 1916, sold at a Sotheby’s auction for a staggering $US$236.4 million, making it the most expensive work of modern art sold at auction.

The most expensive work of art ever sold is the (recovered) painting ‘Salvator Mundi,’ which sold to the Saudi Arabian Crown Prince, Mohammed bin Salman, who paid US$450.3 million for it at a Christie’s Auction in 2017. The painting is attributed to Leonardo Da Vinci, the artist who gave life to the Mona Lisa.

An unexpected lunch, with dear friends, in a special location, with fantastic food and some magnificent wines -the Clos Fourtet 2015, nothing short of a masterpiece- was, to me at least, absolutely priceless.

Darren Gall