“The meaning of life is to find your gift. The purpose of life is to give it away.”

― Pablo Picasso

Prologue:

Having eaten an incredible meal prepared for me by a friend, I was tasked with writing about it and I knew there would be questions of bias and impropriety, that my integrity would be called into question.

I also knew that I was eating one of the most memorable meals I had enjoyed in some time and so, when I had to sit down and write about it I was troubled. How could I write about this extraordinary cuisine and remain true, be faithful to what I was eating and to the experience, without just gushing drivel? How could I convey in a way that was honest and real just how much it meant to me, how much joy it had given me?

I was well aware that because this was my friend and because I knew of his own circumstances and struggles, that these elements were influencing my perceptions of the meal. I began to question even if I could write about it at all? I was struggling and so, I began looking for the answers to these questions amongst the great writers, the men of letters. Perhaps I could seek their guidance as to how I could do the meal, my friend, myself, the article and those who would read it justice. Was it possible or, would it remain in the end, ineffable?

Man who stand on hill with mouth open will wait long time for roast duck to drop in.

-Confucius

Finally, on Friday evening, the 20th of November 2016 at 7.20pm, I took my seat at a table in the Tiger’s Eye Restaurant, there to taste test an eleven course degustation menu that Chef Timothy Bruyns had already postponed three times in as many weeks

The difference between me of the three previous occasions and tonight was that I was battling the flu, a hangover, sleep deprivation and a general mood one could best describe politely as bad.

I knew it meant a lot to chef to get it absolutely perfect, every dish, every nuance of flavour, every garnish; I think it meant more to him than it does to most people about their work, this is not so much his livelihood as it is his life and if dinner was anything less than absolute culinary perfection then he would beat himself up about it for weeks, perhaps months, it would affect his health, his relationships and more, in short, he too would feel pretty damned bad himself.

Tim is a dear, dear friend, like family to me, I have watched his journey in Cambodia up close, at times I have traveled it with him, simply put from someone in the industry for well over quarter of a century, in over twenty countries, ‘Timothy Bruyns is one of the most talented, skilled, creative and extraordinary chef’s I have ever come across’. He does not so much as put love on the plate but pours his heart, anguish, agony and ecstasy all out onto it. So much so, that you start to wonder if he isn’t left cold and shivering on the floor of his kitchen after a night’s performance -it must take a toll, in fact I know it does. However, when it is all about the food it is breathtaking, there is adventure, precision, beauty and risk in every dish, every mouth-full.

A degustation is a journey, from a chef’s perspective Bruyns prefers to do it up on a high wire, dishes are outrageously refined and incredibly complex in ingredients, preparation and technique, there is no safety net. I saw the magician David Blaine catch a bullet in his teeth on TV the other night, no one wanted to pull the trigger so he rigged up a complex apparatus where he could shoot himself, why? Houdini died for his craft, drowned by his own invention, fatally caught in a trap he had set for himself.

The risks Bruyns takes in his kitchen might not be life and death, but they are livelihood and well-being, risking his reputation and his customers favour by insisting on creating dishes that test the abilities and skills of his kitchen and himself to their very limits and beyond.

It is one thing to test a dish and then perfect it; it is another challenge entirely to then regularly recreate that dish absolutely consistently, perfect 20 or 30 times a night, night after night, week after week.

Tim Bruyns will never close a restaurant or go to his grave wondering what if, he demands challenges, seeks them out; when he is under the most enormous pressure he will lock himself away and cook up something of such sublime beauty that it ends up being the perfect diversion.

I hope he won’t mind me writing this, but there have been times when he has paid a heavy price for this approach, a price paid physically, emotionally and even mentally, when it has stressed him to sickness, strained relationships both personal and professional, his organs have threatened to shut down and the black dog has lived on his back, there have been dark periods, they still lurk, not yet completely banished.

There has been regular tilting at windmills and wailing at walls and there have been escapes into moments of reckless abandon, self-inflicted punishment and despair and yes there has been stubborn pigheadedness and hiding behind the propaganda and hyperbole.

However, there is also the bright shining creativity, the unstoppable drive and the devil-may-care, dazzling brilliance.

I talk about my friend like this because it’s difficult to watch at times, an artist and his work but, when it’s magic it is what you live for.

Few in the front of the house understand the hours, the ridiculous hours of work, hard work, in difficult conditions, the heat, the sweat, frustration, the emotion and years of learning that must go into every dish, I have seen a litre of the finest jus, highly refined, start out as eight liters of stock stirred for 20 hours and strained a couple of dozen times, I have tasted the umami from a dried fish, salted, smoked and then left hanging and curing for six months and I have sampled the most tender of beef that takes 52 hours of slow cooking to breakdown the collagen and protein to create fall off the bone, melt in your mouth magic.

It is impossible to measure the worth of these things in terms of price or reward for effort, return on investment.

I knew how much this dinner meant to chef simply because he kept putting it off at the very last minute, he’d done this for reasons personal, professional and most probably psychological, it was high stakes poker and he was going all in against the house. To paraphrase Blaise Pascal, ‘The mind has reasons which reason knows nothing off’, Tim had his reasons.

When we finally got to it, it was extraordinary, something beyond merely exceptionally good food; This dinner will remain an evening’s culinary masterpiece, an evening of such sheer gastronomic perfection that I considered it a singularity, a moment, an event, an experience that can never be repeated as exactly and perfectly as it was that evening.

Because it had been postponed, because I was not feeling great, because I was aware of the struggles my friend had been having, because of all this I was not just turning up to try the food, pass judgment and make my criticisms, my comments and then leave. I was emotionally invested in the drama of it, in all that had gone before and this proved to be transporting in terms of my appreciation of the experience. If this be dinning as fine art there were moments of Mozart, Baryshnikov and Pavarotti, there were moments of Picasso and there were moments of Evil Knievel and Nick Wallenda.

There were arias, crescendos, perfect intonations, poetic lulls, rising allegretto and sweeping legato and there were leaps over the canyon and nailing the landing. Dish after dish displayed flawless technique, inspired creativity, outrageous detail and a masterful, intuitive understanding of the interplay and contrasts between flavours and textures. The flow of the degustation told a story, a beginning then building through the middle up to a climax, before finishing with a flourish; the final coda all at once satisfying and brilliant.

How do we measure flavour, taste, the overall quality of a dinner, the space, the staff, the food, the wine, the water, the crockery, the music, the air temperature, the presentation, the smells, the flavours, the price? How do we pass judgment on a meal? It would be like trying to describe the paintings of Jackson Pollack, or comparing the works of Gustav Mahler.

For centuries many philosophers simply believed it could not be done at all, arguing that sensation (conscious experience) doesn’t take up space and therefore cannot be measured.

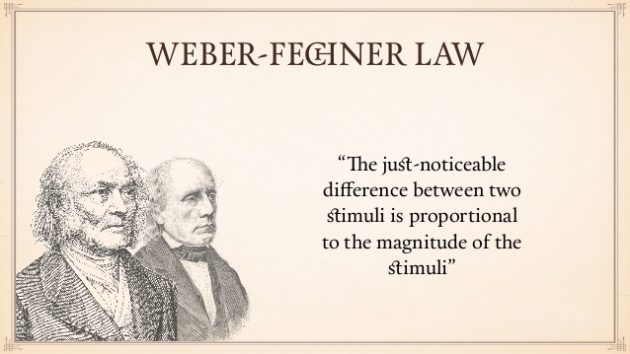

The German physician Ernst Heinrich Weber, (1795 – 1878) is regarded as one of the first persons to attempt to measure physical stimulus in a quantitative manner. Weber was interested in what he called the ‘Just Notable Difference’ in what was being experienced by the senses and how that was being interpreted by the brain; if we started with a glass of water and began dissolving in granules of sugar, at how many granules would we start to perceive it as sweetness? Weber began to understand that the limen point of any given sensation needed to increase in proportion to the initial level of intensity, within the liminal boundaries.

Gustav Fechner, (1801 – 1887) is remembered as a philosopher, a physicist and experimental psychologist and as a pioneer of experimental psychology. Perhaps most fondly of all he is regarded as the founder of psychophysics. Fechner’s 1860 publication ‘Elements of Psychophysics’ was the first work ever written in the field. The term is used to describe how humans perceive physical magnitudes.

Fechner first created Weber’s Law, (dedicated to his teacher at the University of Leipzig, Ernst Weber). The law stated that the perceptible difference in the perceived change in any sensory stimuli was proportional to the actual intensity of the initial stimuli.

His Fechner Law then stated that you could use mathematics to determine at what rate human perception of increases in stimuli where proportional to actual increases in sensory stimuli, that is to say: sensation increases as a logarithm of stimulus intensity or “S = k log R”.

Just as Einstein’s famous equation E=MC2 informed us that energy led to mass at the speed of light squared, thus effectively demonstrating that mass and energy where interchangeable, with S = k log R, Fechner attempted to inform us of the interconnectedness of mind and matter through stimulus intensity and conscious experience.

These laws set the foundation for Psychophysics as a topic of study and trial, now we had a mechanism to measure our sensory responsiveness to stimulation and this could be applied to all of the senses including our sense of smell and our sense of taste.

But just what are we talking about here, when we compare the responsiveness in our brain to the intensity of a sensation transmitted via our senses? We can use a logarithm to measure the entropy but we cannot translate in any meaningful way, except perhaps through language just what our brain is experiencing, the effect on our emotions, what we are feeling and thinking, just what the sensation is ‘telling us’ in our heads.

It would seem to me that whilst we can perhaps establish, to some degree of accuracy, the intensity with which we are experiencing something, just how we are interpreting it and how we feel about that something remains immeasurable but, it is not ineffable, for indeed that is what language is for.

Anatomy of chef and kitchen

Bruyns is straight up skinny, wiry of frame, black, colourless tattoos stretched across translucent white skin with veins blue and visible, like fencing wire wrapped macabrely around a tortured frame. A shock of dark hair on top, clipped tight around the ears the furrowed brow is hypersensitive, a constant screen of moving creases, tics and jolts. Kinetic energy almost crackling under the skin, there is sweat and the constant smell of stale smoke, the angst and the anxiety are palpable.

One gets the sense that Bruyns only barely survived living as Orwell’s poverty line kitchen hand in Paris. (Down and Out in London and Paris, George Orwell -1933) and in the drug addled kitchen chic of Bourdain’s New York culinary underbelly, (Kitchen Confidential, Anthony Bourdain -2000), somehow he came out the other side with scars, pride, considerable knowledge and skill and with his passion for cooking still intact. Bruyns identifies with one of his heroes, Hunter S. Thompson, he certainly has Thompson’s unbridled brilliance but, there is more than a little culinary ‘rebel against the world’ James Dean in his persona.

The kitchen is indeed a Tiger cage, a small rectangular box of cold steel, chipped, white glossy tiles, sharp blades, hot plates, fire, ice and steam, it is a place where blood is spilt and flesh is seared and it is not always the food, a chef’s will is forged like iron in these fires, a crucible where dreams can die violently on the killing floor. And yet here, this is also a studio of sorts an atelier that turns out high culinary art, beautiful food, poetry on a plate with a deftness and lightness, with touches ephemeral and effeminate, here is finesse with microscopic precision. In a sort of version of Fechner’s Logarithm, it is really something incredible to first think up dishes like this and then bring them into being, share them with the world and then try to measure the impact they have on diners and the public at large.

Below the Surface, Behind the Pass

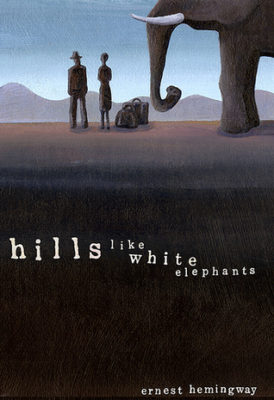

Ernest Hemingway once said, ‘If a writer of prose knows enough of what he is writing about he may omit things that he knows and the reader, if the writer is writing truly enough, will have a feeling of those things as strongly as though the writer had stated them. The dignity of movement of an iceberg is due to only one-eighth of it being above water.

A writer who omits things because he does not know them only makes hollow places in his writing.’

So much of Hemingway’s greatness as a writer came because of what was not said, by the power of what you knew where the things behind his writing, beneath the surface and the truth in it. This was his genius and this is what connected him so powerfully with his audience.

It opens with a line about White Elephants, unwanted gifts that become burdens and closes with a line about other people being reasonable. Hemingway’s ‘Hills like White Elephants’ was first published in the experimental art and literature magazine ‘Transition’ in August, 1927 and then later that same year in his collection of short stories titled ‘Men without Women’. It is a short story of only 1,465 words, yet what weight and power and certainty in every sentence, what simply incredible writing. The undercurrent, like a silent, malevolent rip, one senses the enormous iceberg below the surface immediately, from the very first sentence and here -as you read on- it is like lead around your ankles, dragging you down into the black abyss.

This is Hemingway’s mastery, his power, it is a masterpiece in minimalist prose for the frisson it sets crackling below the surface right from the get go, like a beast in the dark whose snarl can almost be heard, ready to wreak violence upon the reader, or an impossibly sad tragedy about to unfold and stain one’s innocence and one’s hope. Yet the author never mentions the subject matter, it just hangs there unspoken, unwritten and yet understood and undeniably felt.

The subject matter is abortion, imagine the sensitivity at the time and place of the story, when it was written, who was writing it, even today, consider how emotionally charged a topic it is.

I have studied the choice of every single word of it, every piece of punctuation, followed the arc and timbre of every sentence, the choice of every person’s name, every place name, the setting, its damned near perfect.

When Chef Timothy Bruyns delivers one of the small, almost tapas size dishes that make up his eleven course degustation you get a sense from its complexity of the story below the surface but, even upon eating the dish, which you will most certainly appreciate, you will never fully comprehend the details, they are hard to process in facts, in weeks of searching for ingredients, hours and sometimes days of preparation, cooking, molecular realignment, the years of training and studying. One small poem on a plate is actually Wagner’s Ring Cycle in the kitchen, to arrive at this one moment of culinary bliss.

In that moment, I think of the work of someone who was certainly not a minimalist or even a writer of short stories, I think of someone who left absolutely nothing out and devoted more words than perhaps anyone else –ever- on the minutiae in our daily lives, he did so in the longest novel in the world at just over 1.2 million words. I am thinking of course of Marcel Proust and his amazing, ‘a la Recherche du Temps Perdu’ (In Search of Lost Time) which was released in seven volumes over fourteen years between 1913 and 1927. Proust began working on it in 1909 and continued to do so up until his death in 1927. The work has twice as many words as War and Peace, it has been rated by critics at various times as the greatest book ever written and remains at the very top of many if not most lists to this day.

Precious Fragments

Proust had his own, most famous moment, today it is known as a ‘Proustian Moment’ or a ‘Madeleine Moment’ Proust himself gave it the name ‘involuntary memory’. In Volume One of In Search of Lost Time, ‘Swann’s Way’ Proust wrote:

And suddenly the memory returns. The taste was that of the little crumb of madeleine which on Sunday mornings at Combray (because on those mornings I did not go out before church-time), when I went to say good day to her in her bedroom, my aunt Léonie used to give me, dipping it first in her own cup of real or of lime-flower tea.

The sight of the little madeleine had recalled nothing to my mind before I tasted it; perhaps because I had so often seen such things in the interval, without tasting them, on the trays in pastry-cooks’ windows, that their image had dissociated itself from those Combray days to take its place among others more recent; perhaps because of those memories, so long abandoned and put out of mind, nothing now survived, everything was scattered; the forms of things, including that of the little scallop-shell of pastry, so richly sensual under its severe, religious folds, were either obliterated or had been so long dormant as to have lost the power of expansion which would have allowed them to resume their place in my consciousness.

But when from a long-distant past nothing subsists, after the people are dead, after the things are broken and scattered, still, alone, more fragile, but with more vitality, more unsubstantial, more persistent, more faithful, the smell and taste of things remain poised a long time, like souls, ready to remind us, waiting and hoping for their moment, amid the ruins of all the rest; and bear unfaltering, in the tiny and almost impalpable drop of their essence, the vast structure of recollection.

And once I had recognized the taste of the crumb of madeleine soaked in her decoction of lime-flowers which my aunt used to give me (although I did not yet know and must long postpone the discovery of why this memory made me so happy) immediately the old grey house upon the street, where her room was, rose up like the scenery of a theatre to attach itself to the little pavilion, opening on to the garden, which had been built out behind it for my parents (the isolated panel which until that moment had been all that I could see); and with the house the town, from morning to night and in all weathers, the Square where I was sent before luncheon, the streets along which I used to run errands, the country roads we took when it was fine. And just as the Japanese amuse themselves by filling a porcelain bowl with water and steeping in it little crumbs of paper which until then are without character or form, but, the moment they become wet, stretch themselves and bend, take on colour and distinctive shape, become flowers or houses or people, permanent and recognisable, so in that moment all the flowers in our garden and in M. Swann’s park, and the water-lilies on the Vivonne and the good folk of the village and their little dwellings and the parish church and the whole of Combray and of its surroundings, taking their proper shapes and growing solid, sprang into being, town and gardens alike, all from my cup of tea.

And so, the narrator came to learn -and Proust was to teach us- this moment of involuntary memory was to unlock so much more in his mind, reveal so much more to him than mere memory, it set the foundations for a way of looking at life and living happily.

For Proust, happiness was not about searching for new landscapes but in seeing the world with new eyes and one of the most significant ways to do this was to look at life through the eyes of our artists and artisans. We must break through the prism of dead habit from which we look at life and understand that it is not our lives that are mediocre and boring but our own image of life that needs adjustment.

Artists and artisans are important because they remind us that life is interesting, fascinating, complex and beautiful, thereby helping us to dispel our feelings of boredom and ingratitude about everyday life.

Proust felt that true artists look at life with fresh and vibrant eyes, like the unspoiled eyes of children, whose vision is not stained by habit, fame or the disappointment of love.

They can help us to appreciate life with a new sensitivity and bring true happiness into our everyday lives. Proust’s favourite artist was said to be Vermeer, a painter who truly new how to bring charm to everyday life. Some of Proust’s most beautiful prose is of when he is describing simple moments of everyday life, like smelling the flowers in spring or appreciating the changing light of the sun on the sea.

Proust was born at the end of the Franco – Prussian war, during the violence of the suppression of Paris. He was a wan and sickly child that would suffer from ailments and ill health for his entire life. His chronic hypochondria was of no help to the matter and for much of the writing of his great work he confined himself to his bedroom, which he had lined with cork to keep the noise out. Though he was born into a family of some wealth and position, his could be seen as a somewhat sad and unadventurous life and yet his work has been described as the very antidote to such a thing, no less than a way to learn to live a happy life.

His father Dr. Adrein Proust was one of Europe’s great doctors, honoured for his work and the inventor of the ‘cordon sanitaire’ – the quarantined ring around an infected area – that helped with the eradication of Cholera in France, he was bitterly disappointed in his son’s lack of ambition and application to a respectable career. At his father’s behest, Proust took a job at the Bibliothèque Mazarine in the summer of 1896 but went to considerable effort to obtain a sick leave that then extended for several years until he was considered to have resigned. He never worked at his job and he did not move from his parents’ apartment until after both had died.

Proust confided to his housekeeper, Celeste that he wished “If only I could do as much good for humanity with my books as my father has done with his work”. Looking back ninety four years after his own death, anyone would conclude that he has succeeded quite brilliantly.

As I sit at the table contemplating the art in front of me, I am aware that I am looking at food, at ingredients, at cooking through the lens of an artist and an artisan who has interpreted and created a piece of my world in an extraordinary way and I am in awe at what he has done, what I am ingesting and feeling with my senses and appreciating, seeing the world in a new light -with a little help from Proust.

“Tell me what you eat and I’ll tell you what you are”

– The Physiology of Taste: Meditations on Transcendental Gastronomy, Jean Brillat-Savarin, 1825

Timothy Bruyns is from South Africa and has travelled and studied his trade through several continents including Africa, Europe and South East Asia. The simple fact is, he could right now be cooking and probably earning considerable fame and fortune in the great economic and gastronomic cities of the world today, Paris, London, New York, Sydney, Tokyo or Hong Kong.

He found his way to the foundation kitchen of Cambodia’s first private luxury island resort, Song Saa. After a few years there he left the island to follow his heart, open his own restaurant and remain in Cambodia to do so. Cooking in Cambodia has proven a challenging and informative journey, he continues to grow and explore as a chef and to constantly push himself beyond his comfort zone.

A restaurant is also a business and there is high risk and financial danger in what Tim is attempting to do with his little jewel of a restaurant on Sothearos Boulevard, opposite the infamous ‘White Building’ as it was known in less grimier days. This is hardly a prestigious address and definitely not safe ground from which to build a financial empire. However, it is just what philologist, philosopher and writer Friedrich Nietzsche urges us to do, to live life dangerously and build our cities on the slopes of Mount Vesuvius, believing that the greatest results are wrought from the most difficult striving; the most beautiful flowers are borne of the rockiest ground, as Nietzsche would put it.

He is often remembered for his much used quote, “Whatever doesn’t kill me only makes me stronger” yet what he wanted to teach us with his ‘self-overcoming’ was how to rise above our personal circumstances and our own difficulties to embrace whatever life throws at us and in doing so we reach our full potential and become what he called ‘Ubermensch’.

The American philosopher, essayist, poet and author Henry David Thoreau wrote: “I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived. I did not wish to live what was not life, living is so dear; nor did I wish to practise resignation, unless it was quite necessary. I wanted to live deep and suck out all the marrow of life…”

Describing Bruyns’ cuisine is not easy, putting a label on it should perhaps be unnecessary but we need our points of reference, ‘fusion’ is an out of favour term once used to describe a meeting of eastern and western ingredients and disciplines but, this has now been dumbed down to resemble ‘confusion’ one scribe noting it was now more often than not a combination of the ‘worst of both worlds’. Other terms thrown about are: contemporary, modern, pangaean, Pacific Rim and global, although none of these are apt in my opinion.

Writers from Voltaire to Goethe have urged us to travel more, to question more, to be good and brave and challenge accepted norms, to discover and to try through our instruments and gifts to make the world just that little bit better a place.

As a writer and as a thinker I am the first to admit that I am moved -as Emerson would say: ‘by strange sympathies’ and I do believe there is a divine spark in each of us. I have come to describe Bruyns’ food as transcendental a cuisine that transcends styles, borders and techniques and in doing so connects them all.

I have seen him spend his years in Cambodia searching and foraging and learning about ingredients and cooking techniques as he looks to marry his formal training and understanding of cooking and ingredients with local precepts and lore of food, meals and cooking.

There are perhaps sexier countries and cuisines to explore and take learning from however, Cambodian cuisine has been stolen, borrowed and lent to its neighbouring countries through the great empires of its history and much of that was then wiped out in its own country, through one of modern history’s cruelest chapters. Food in Cambodia has been sent back to its most basic and primal elements and there is much that can be studied from that and developed as a refined cuisine re-emerges from the darkness. This is where I think a chef like Bruyns can shine and be important for the culinary landscape here, as have a few other international chefs who have adopted the country as their own. I see this as another transcendental element of Bruyns’ cuisine and it could thrive in an age of emerging culinary tourism in the region, as Cambodia continues to grow as a tourist destination.

The Tiger’s Tale

The first dish was a fried Tofu Laab Rice Cake with Smoked Aubergine and Hot Basil; it was outstanding in its texture and mouth-feel with a hint of crunch to the rice paper dumpling. I adored this dumpling and it could easily become a favourite, it is a subtle and beautifully layered dish, the hot basil aioli dazzled, I was however looking for a chilli kick and some of Bruyns’ own house-made chilli sauce should do the trick nicely next time around.

The exceptional opening dish was followed by a complex arrangement of colours and aromas served on a large tablespoon: A Tartar of Prawn with Nam Prik, Tom Kha gel, Sour Nam Prik puree, Avocado, Banana Heart, Banana Blossom, Sweet Basil Puree and cherry Tomato.

The prawns were cooked in a Sous Vide at sixty degrees Celsius for 20 minutes with lime leaf oil, Thai cardamom and lemongrass, giving them a beautiful texture and flavour. Namh Prik is the irresistible Thai dipping sauce made with dried chilli, garlic, shallots, lime juice and shrimp paste which gives a nice vibrancy to the dish and a moment of genius to serve Tom Kha as a gel, normally a light coconut based hot and sour soup served with chicken in Thailand, divine here as part of a complex dish that works wonders across the taste buds and in the olfactory receptors.

Third dish, an incredibly airy and light Mousse of Kep Mangrove Crab, Flaked Crab, Fried Pork Skin, Pickled Cucumber, Soy and Lime Puree with Plantation Fresh, Kampot Green Peppercorns.

The technique on this dish is outstanding, the results stunning. A subtle and incredibly refined mousse of crab which starts off with the large, meaty Mangrove crab from Kep being poached in a sort of Asian style Bouillon that includes dried chilli, smoked galangal, kaffir lime leaf, lemongrass and seasoning.

After the crab is poached is must be chilled down to almost frozen to ensure it will not cause the mousse to split, the crab meat is blended with lime juice, with the cream very slowly added, this mix is then passed through a very fine mesh sieve and finally whipped cream is very gently folded into it and then seasoned again before service.

The pig’s skin crackle component sees the flesh scraped bare and then slow cooked overnight in the water oven at 75C to breakdown the tissue and really soften the texture. It is then dried above the oven for two days before being cooked at a very high heat in hot, high smoke point oil which gives the skin its unique, crispy, puffed texture, making it an exceptional accompaniment to the mousse. The dish is served with a sort of Chinese version of a Japanese Ponzu sauce, incorporating soy sauce and lime juice that is set with agar to render it into a sort of brittle jelly.

Pickled vegetables are pickled in vacuum sealed bags that help draw the pickling liquid into the vegetable whilst also preserving chlorophylls and therefore colour in the green vegetables. And the bright acidity here acts as a nice foil to the creamy mousse and crackling pig skin.

The next dish was a little more substantial, a Salt Cured, 42 degree Confit Salmon, White Onion Panna Cotta, Caviar, Coriander & Sesame Pistou, Fermented and Fresh Soy Bean mix, a julienne of Ginger, Spring Onion, a Sesame Crisp and Avocado.

Confit comes from the French word confire, which means ‘to preserve’, as a cooking term it is one of the oldest forms of cooking and preserving. Confit in terms of cooking describes when a food is cooked in grease or oil at low temperatures, as opposed to deep frying which takes place at much higher temperatures. Today the term is usually used to mean a long and very slow cooking period at low temperatures.

First the salmon is salt cured with a house made herb salt, which in itself takes around a week to prepare, using approximately a kilogram of fresh herbs and a kilogram of soil, the herbs are moist and with the salt being hygroscopic it pulls the moisture from the herbs into itself and in doing so the flavours of the herbs are infused into the salt.

When the Salmon is then cured in the herb salt it not only draws the moisture out and seasoning the salmon it also adds a complexity of flavour with the herbs in the salt.

The salmon is cooked at 42 degrees Celsius for approximately 25minutes, Tim employs a logarithm involving the size of the portion and the length of time needed to get just the right cook. The low temperature process breaks down and breaks down the collagens and connective tissues, unfurling the amino chains, giving the fish an incredibly delicate and soft texture whilst retaining all of its natural oils without undergoing any vulcanization or maillard reaction.

There is a stunning white onion panna cotta, instead of a bagel we get a sesame crisp, there is a touch of caviar to bring a little fresh taste of the sea and a pistou which is finer than a pesto, made with blanched coriander, and then there are spring onion, avocado, fresh and fermented soy beans and pickled ginger. The accompaniments here were exceptional, working magically with the protein. It was an outstanding interplay of flavours, textures, incredible balance and sublime complexity. There was umami, piquancy, freshness, richness and savouriness, like one of Wagner’s finer moments -all the instruments of the orchestra seem to be playing different tunes yet complementing each other in perfect harmony.

The salmon itself was simply amazing, one of the finest I have every enjoyed, normally, whilst I am a huge fan of fresh, raw salmon, I avoid the strong, oily, fishy aromas and flavours of the cooked version. This cooked salmon is something else, something elegant and divine, a cooked salmon not like I have ever had before.

The next dish is served with a little theatre under a glass cloche, a Salt and Sugar Cured, Hot Smoked Duck Breast slices with Fresh Turmeric pickled Cauliflower, Quail Egg and Garlic puree. Star Anise, Cumin, Coriander and juniper in the cure adds deft complexity to the duck’s flavour, after curing it is rinsed, cooled and then the skin rendered down before being hot smoked to the chef’s consistency of cook. Some of the duck breast is used to make a mousse and give a play on texture and the rest sliced for plating, I have had versions of this dish before and Tim is a chef who his is constantly tinkering with dishes and trying to evolve them, this is the latest and best version of it I have tried. The turmeric pickled cauliflower nicely pierces through the smoky, gaminess of the protein. The quail egg is a nice touch and the roasted garlic puree a beautiful complimentary flavour to the protein.

Then we go to an amazing Terrine of Braised Pigs head, Crumbed and Fried with Sous Vide white onion, fresh Soy bean, Sesame Dressing, White Onion Puree and Marinated Shitake Mushroom.

The head is seared, singed, plucked and cleaned and then brined for 24 hours, with a salt brine infused with star anise, dried chilli, lemongrass and ginger. The sodium in the brine solution changes the charge on the ions in the water, allowing the moisture to be absorbed by the cells of the protein and adding more flavour and flavour complexity.

The head is then braised in a sort of Khmer, Kor Sach Chrouk or thick pork soup that consists of palm sugar, pepper and soy sauce for 15 hours, until the meat is virtually falling of the bone.

The meat is then taken off the skull in fairly large, whole pieces and then wrapped in clean film as tight as possible and then pin pricks are put in to get out all of the air. The clean fill is then wrapped tightly into ‘au torchon’ an old technique of tightly wrapping terrine type dishes in cloth or clean film, recently made popular by a recipe for “Foie Gras Au Torchon” by Thomas Keller in his 1999 book, “The French Laundry Cookbook.”

A slice of the pigs head torchon is then floured, egg washed and fried in panko breadcrumbs giving the dish a slight Japanese ‘tonkatsu’ crunch element to it. The pork is complimented beautifully and subtly with a sous vide white onion which vacuum sealed with salt, brown sugar and lemon grass, making it tender and sweet with a little aromatic lemongrass, then some spring onion, fresh soy, soy marinated shitake and a sesame dressing.

The final protein is an exceptional dish and a fitting climax to the evening, an essay in beef and ode; it is a Sous Vide Beef Short rib, Bone Marrow Crust, Beef and Star anise Jus, Sweet Potato Mash, Grilled King Mushroom, and Confit Garlic Foam.

The Beef short rib is salt cured and then sous vide for 52 hours, topped with a bone marrow crust, the marrow broken down and soaked in ice water for two days, then rendered down and whipped for 30 minutes before stirring in breadcrumbs, salt, pepper and shallots and placing on top of the short rib.

The jus is perhaps the best I have ever tried, traditionally beginning life with roasted beef bones, and a classic mirepoix, of roughly chopped onions, carrots, and celery to which Bruyns adds leeks and garlic, making sure he adds the right vegetable at the right time to get the perfect caramelization and sweetness without over cooking. The stock also includes peeled and deseeded roast tomato and reduced red wine.

This is all added to about eight litres of water and left to simmer for twenty four hours to extract flavour, whilst simmering impurities are skimmed from the top and once ready the stock is very gently poured out between three layers of muslin cloth and a fine sieve. Then the stock is reduced and reduced until it reaches the point of a demi-glace.

Bruyns uses his brazing master stock which keeps having bones added and fat removed over and over again and also contains a little cinnamon, soy, ginger, star anise, clove and rice wine vinegar to which he then adds the corn flour, balancing it out with a little sugar. The intensity and clarity the jus has to be tried to be believed.

The grilled king mushroom, sweet potato mash and confit garlic foam all tend to reinforce the incredible flavours and layers of beef upon beef upon beef, the dish is something truly incredible, like a master’s thesis in Beef.

The dessert is a mind-boggling work of art and culinary skill, a Homemade Yoghurt Mousse, Dehydrated Yoghurt Crisps, Yoghurt mint puree, Compressed and Fresh Watermelon, Roselle Jelly and Consommé, White Chocolate Mousse and Meringue.

Firstly the dessert dish looks like it should be framed and hanging in a gallery, all brilliant, whites, creams, pinks, fuchsias and reds. The dish itself is light, airy, clean and fresh with subtle textural shifts and understated sweetness. It is sublime, a perfect way to end an incredible meal. I feel like I have been through some sort of culinary opera performance, full of complex yet elegant Mozart moments, Rousseau like moments of rich emotion and grand moments reminiscent of Verdi’s Aida, and then here we have ended on a brilliantly light and uplifting coda.

It has been one of the great meals, a tour-de-force handled with masterful deftness, never overpowering and yet never failing to impress brilliantly. I am in awe of the talent, skill and imagination on display, rendered as flavours, aromas and textures and presented in visually stunning ways. I am happy for my friend, he has triumphed once more and like great literature, like great art, he has created something magical for others to enjoy and I hope he finds joy in that as well.

How do we measure flavour, taste, the overall quality of a dinner, the space, the staff, the food, the wine, the water, the crockery, the music, the air temperature, the presentation, the smells, the flavours and the price? How do we pass judgment on a meal?

In the 2007 computer-animated movie named ‘Ratatouille’, the lead character is Remy, a rat with ambitions to be a chef; he idolizes the late great chef Auguste Gusteau who lived by the motto ‘anyone can cook’. Remy prepares the film’s namesake dish for the fearsome and powerful restaurant critic Anton Ego, whose last review of Auguste Gusteau’s restaurant was negative, costing it one of its precious (Michelin) stars.

Remy prepares a variation of ratatouille, which reminds an astonished Ego of his mother’s cooking and transforms him in a Proustian moment back to his mother’s kitchen and her unconditional love. The effect on him is profound; his review is favourable, announcing Remy as the finest chef in France as the film moves to its Disneyesque happy ending.

On Wednesday the 17th of December I had my answer, the launch of the degustation to the world at large, opening night was a full house, 40 people in a restaurant that can normally only comfortably accommodate 34. 40 people by 10 courses meant that the kitchen was going to have to smash out 400 dishes in a little over two hours, an immense task even with basic food let alone food at this level of sophistication and refinement.

I was there with a beautiful woman and 19 other friends and as we talked and joked and as we drank the wines that I had selected to pair to the dishes, I took a moment to look around. I saw the laughter, the smiles, the glow on people’s faces and the joy when each new dish was presented and the happiness, the overall buzz going on in the room.

I could see that it was special and that people were having a great night and this was a good thing, a memorable thing, a night in Phnom Penh when it was great to be alive and in the end that was all that mattered.

I caught Bruyns sneaking out unobtrusively the minute his team had finished their service, 400 dishes in two hours and he was dashing home to be with his wife, whom he told me was nursing a mild concussion from an accident at home the day before. There was not time to bask in any glory, he would be back in the kitchen at first light the next day.

Spontaneously, I wrote my thank you on one of the menus and passed it around asking everyone on my table to sign it and they all happily agreed, I then gave it to one of chef’s business partners, who was also there and I asked if they wouldn’t mind passing it on.

I am not sure how you measure a meal but, I know great food and great wine moves me in ways great art does and I am moved to write about it and try to convey the feelings and emotions it evokes in me.

Since that first tasting to the opening night dinner up until now, I have written over seven and a half thousand words on this one meal, deleted many more and added a few others and so here you have it.

This is in the end, not my measure but my story of this meal and the life of it, the story behind it. In the process I have put out there the love and the frustration and the joy and the brotherhood I have shared and continue to share with my friend, someone whom I ultimately admire and who has often inspired me.

Perhaps after all, I just hope it will inspire you to try it for yourself and I hope you enjoy it and as my story informs your meal, your meal informs your understanding of my story and we make that little connection, that little bit of magical bonding over food, over art. And it is in that moment, I hope our world is just that little bit better for it.