Shomurice

At Red Mountain Estate Winery in central Myanmar, renowned ‘Master Chef’ judge U Ye is redefining one of Japan’s most iconic and theatrical dishes, ‘omurice,’ giving it a unique and distinctly local quality.

“In this universe, there’s just you and me.”

You stared blankly at me. “But all the people on earth…”

“All you. Different incarnations of you.”

― Andy Weir, The Egg

In his 2009 short story ‘The Egg,’ science fiction writer Andy Weir presents a thought experiment and existential concept: the idea that every human being who has ever lived, or will ever live, is actually the same entity, experiencing different lives across time and space. The goal being to experience all perspectives so that this singular entity might then transcend.

We are up in the Shan Hills, high above Inle Lake, and my dear friend and national treasure, chef, baker, cheesemaker, agronomist, food historian, and more that is U Ye (Sharky), seems as omnipresent as Weir’s conjecture. He is in his element. Frenetic, fidgety, a man on fire, he never stops moving, talking, thinking, kinetic energy personified, mind throwing out ideas like sparks, distilling thoughts, ever ready to light a match under any number of them. As he buzzes about the restaurant, a man of action, it is high performance, dramatic, almost artistic; it is creativity in constant motion.

As the child of a diplomat, U Ye led a peripatetic childhood, travelling and living in many different countries for relatively short periods of time. Eventually settling in Switzerland, he became a successful operator of bars, clubs, and restaurant chains, before establishing his own company and earning his new nickname.

Sharky returned to his native Myanmar in 1996 and fell in love with a place he had felt distanced from as a child. There was discovery, reconnection, affiliation, and affection; he was finally home.

Today, Sharky is a protean entity in his native land, a farmer, producer, restaurateur, coffee roaster, bread maker, cheesemaker, communicator, caterer and more. Perhaps most importantly of all, he is a cultivator, developer, promoter, believer and great champion of the quality and potential of local Myanmar agriculture and produce. Seasoned, well-travelled, a true Renaissance man, U Ye is indeed many things, seeming to have crammed more life into (or is it squeezed out more lifetimes from) than anyone is supposed to have a right to in one cycle of samsara.

“Talent hits a target no one else can hit. Genius hits a target no one else can see.”

― Arthur Schopenhauer

Tampopo

Tampopo is a 1985 Japanese satirical comedy movie directed by Juzo Itami, it promoted itself as the first “ramen western“, a play on “spaghetti western”, the exonymic nickname given to a genre of films by Italian director Sergio Leone, with most starring the Hollywood actor Clint Eastwood. The story centres on a struggling ramen shop owner’s quest to create the perfect ramen, with surreal, food-themed vignettes woven throughout the narrative.

For lovers of food-related film, it is a cult classic with a global following. Ostensibly about ramen and ramen-related culture, the film also features an iconic omurice scene. A young boy and a homeless man (who used to be a chef) break into a restaurant so that he can cook the hungry lad a simple dish of ketchup rice and an omelette.

The homeless chef prepares a simple mound of rice mixed with ketchup and then prepares the eggs, scrambling them constantly with his saibashi (cooking chopsticks). With the centre of the omelette representing something like an eggy version of burrata cheese, it peels back and cascades down over the rice, to the wide-eyed wonder of the hungry child and a great many of the watching audience as well.

The dish was specifically developed for the movie, the result of a collaboration between director Juzo Itami and chef Masaaki Modegi, the owner of Taimeiken, a famous yōshoku (Japanese-style Western cuisine) restaurant in Tokyo.

The inspiration for the dish’s appearance came from the film’s title: Tampopo, which means “dandelion” in Japanese. When the soft egg spills out over the rice, it is meant to resemble a dandelion bursting into bloom.

The scene was filmed in the kitchen of the Taimeiken restaurant, and the close-up shots of the preparation feature the hands of chef Masaaki Modegi himself, ensuring culinary authenticity.

The “Tampopo style” omurice became a sensation following the film’s release and a permanent fixture on the Taimeiken menu. The technique proved so popular that it has since become a standard and highly sought-after method for making omurice in Japan and a signature dish for many restaurants around the world.

The film Tampopo focuses on the idea that food is a metaphor for life, love, and the human experience, exploring themes of desire, cultural identity, and the absurdity of obsession, using food as a unifying theme. It uses food to comment on social structures and human behaviour, celebrating the artistry of cooking and eating, while also critiquing consumer culture and the often-confronting realities of our relationship with food.

East Eats West

Omurice (オムライス) omu-raisu, has its origins in Yōshoku cuisine, which originated in Japan during the Meiji period (1868–1912). In essence, it was a way of adapting Western cuisine to Japanese ingredients and tastes during an era of momentous change, modernization, and engagement with the Western world. It began in the port cities like Kobe and eventually spread to become popular in modern Japanese food culture.

The exact birthplace of omurice is disputed, with stories of it originating in either Renga-tei, which opened in Tokyo’s Ginza district in 1895, or Hokkyokusei, which opened its first restaurant in 1922. It is now a chain specializing in omurice, with its main restaurant in the Shinsaibashi district of Osaka.

Kuidaore

Many consider Osaka the food capital of Japan; some call it the ‘kitchen of the nation,’ (tenka no daidokoro) based on its historical role as a major supplier of food during the Edo Period. Osakan people have a reputation for a deep love and appreciation of food and dining culture which is celebrated with an affectionate saying, ‘kuidaore,’ this can be loosely translated to, ‘eat until you have no money left.’ It is said with a smile and is meant to be a recognition of the incredible food and dining scene in the city.

OVA

Earlier versions of omurice were simple, more like a gently cooked omelette, placed on top of rice and then smeared with tomato ketchup. Two newer styles of omurice evolved and have taken the social-media-connected world by storm. They are known as:

Tornado Omurice (Twist Omelette Style)

This style is known for its intricate and visually appealing presentation. The egg is cooked in a specific, and very skilful manner using chopsticks to twist it into a vortex or spiral shape as it sets in the pan. The resulting tornado-shaped omelette is then draped over a dome of fried rice to completely encase it. This technique requires dexterity and a good non-stick pan, making it a popular subject for viral cooking videos.

Fluffy and Runny Omurice (Fuwatoro Style)

The highly popular variation is the fuwatoro omurice (fluffy and runny). This style features a half-cooked, moist, and creamy omelette placed atop the rice. The chef then cuts the omelette open, allowing the molten interior to spill out and envelop the rice. This is the technique popularized by the film Tampopo.

Both these techniques turn simple eggs and rice into an elegant, aesthetically pleasing culinary experience and globally viral phenomenon on social media.

Kichi Kichi

Motokichi Yukimura, who is today known as the viral omurice guy, opened his first restaurant, Yoshoku, in Kyoto’s historic Uzumasa district in 1978. Whilst omurice was on the very first menu, it was many years before it evolved into his signature style of artistry and performance piece that it is today.

Since his restaurant was close to Toei Kyoto Studio—a theme park where jidaigeki (period drama) movies are filmed—many actors would pop in for a meal. This is how he heard of the legendary fuwatoro style omurice in Tampopo, and that several restaurants in Tokyo were serving it with enormous success.

Yukimura began working on his omurice technique, eventually gaining enough confidence to serve it as an ‘off-menu’ dish only. By the time he relocated to his new restaurant in Kyoto’s Pontocho district, he was ready to put it on the menu. He says it took him about six years to get it to the right level, to hone the skill and create a sort of kitchen performance around it. He claims he is still evolving and reimagining the dish.

At seventy years old, Motokichi Yukimura is a global digital phenomenon, doing pop-up kitchens and making television appearances all over the world. His famous, fourteen-seat Kichi Kichi Omurice restaurant in Kyoto has become a must-visit destination for food lovers from around the globe, where people will wait for hours to watch him prepare one of his signature omurice dishes for them.

Yukimura considers himself to be a self-styled “omurice evangelist,” his motto is “Spreading Happiness to the World with Omurice,” and his belief is in the power of food to bring joy and connect people across cultures.

The Fuwatoro-style omurice at Kichi Kichi transcends dining—it is a sensory event, marrying nuanced flavour with theatrical artistry. Chef Yukimura doesn’t cook; he orchestrates. The foundation is ketchup-infused rice—sautéed with chicken and onion until fragrant and tangy—then sculpted into a taut, perfect dome.

But the true draw is the egg.

In a small, seasoned pan, he whips the eggs to a perfect emulsion, then cooks them with startling speed. The chef’s hand becomes a blur, constantly swirling the pan, and drawing curd-like strands of egg to the middle, so as to achieve its mythical texture: the exterior holds its form while the interior remains a glistening, liquid gold. What follows is a moment of intense anticipation: the omelette is placed on the rice, and a sharp knife makes a clean incision. The creamy centre surrenders instantly, spreading and spilling over the rice like a golden avalanche, and is finally dressed in a whisper of demi-glace.

The emotional resonance of this meal is profound. Chef Yukimura’s kitchen is a stage, and his joyful, theatrical demeanour invites participation. His playful banter and radiant passion create a celebratory atmosphere. To visit Kichi Kichi is to witness a culinary ritual, transforming a simple, humble egg into a memorable act of delicious, comforting art.

“People will forget what you said, people will forget what you did, but people will never forget how you made them feel.”

― Hector Garcia Puigcerver, The Book of Ichigo Ichie

One Lifetime, One Meeting: 一期一会

Sen no Rikyū (1522 – 1591), was a Japanese tea master considered the most important influence on chanoyu, the Japanese “Way of Tea”, particularly the tradition of wabi cha.

Wabi-Cha is a style of the Japanese tea ceremony that emphasizes simplicity, rustic aesthetics, and a deep spiritual connection rooted in Zen Buddhism. It developed as a reaction against the extravagance of earlier tea parties, focusing instead on natural materials, humble settings, and mindful interaction between the host and guest.

Sen no Rikyū stated that the tea ceremony can be explained by the simple phrase: ichi-go ichi-e: one time, one meeting. The ceremony is not about taste; it is all about enjoying the moment and remembering that this moment will never happen again.

Rikyū’s apprentice Yamanoue Sōji instructs in the Yamanoue Sōji Ki to give respect to your host “as though it were a meeting that could occur only once in a lifetime.”

In 1858, Ii Naosuke, Tairō of the Tokugawa shogunate, elaborated on the concept in Chanoyu Ichie Shū:

“Great attention should be given to a tea gathering, which we can speak of as “one time, one meeting” (ichi-go, ichi-e)… Viewed this way, the meeting is a once-in-a-lifetime occasion. The host, accordingly, must, in true sincerity, take the greatest care with every aspect of the gathering and devote himself entirely to it….The guests, for their part, must understand that the gathering cannot occur again…. And must also participate it with true sincerity. This is what is meant by “one time, one meeting.”

This passage established the yojijukugo (four-letter idiomatic) form 一期一会 as we know it today.

Another important aspect of the philosophy of ichi-go, ichi-e is to move on from mistakes and keep going, not dwell on the mistake, stop what you are doing and lose heart, instead understand that you must continue with everything you have, in that moment, to recover, keep going and give it your very best, because you may never get another chance to put that action into practice.

To me, the philosophy of ichi-go, ichi-e, encapsulates the guiding principles of Chef Kichi Kichi, who appears to be fully present and engaged in every omurice he creates. He cherishes each encounter with people, and behaves as if he understands that this exact moment will never happen again, he gives total focus and sincerity to each act.

He has said himself that an important part of his daily regimen is to practice gratitude and reflection. Careful not to dwell on mistakes but notice them quickly and trust that you can learn and improve.

Zen encourages letting go of attachments to the past and anxieties about the future. True peace and joy are found only in the present moment.

Shomurice

I do not know how long he had been thinking about it, or honing his skills, but U Ye, ‘Sharky’ is a fine exponent of the art of creating omurice. He also developed a ‘bullet-proof’ technique to train up our chefs at the winery restaurant.

The next step was to create, using omurice as its base, a dish that was uniquely Shan and appreciated by visitors to the winery from all over Myanmar.

To give it a unique name that incorporated its origins in both Japan as the original dish and Shan State as the local variant, and also pay respect to its creator Sharky, I dubbed this version, ‘Shomurice.’

Tazaungdaing

The Tazaungdaing Festival in Myanmar is held on the full moon day of Tazaungmon, the eighth month of the Burmese calendar, and is celebrated as a national holiday. It marks the end of the rainy season and the beginning of the Kathina season, a time when monks are offered new robes and alms. At Red Mountain Estate winery, in the hills near Nyaung Shwe (where I make wine), it also marks the beginning of the ripening season.

Atop the mountains nearby is Taunggyi, the capital city of Shan State. The city’s hot-air balloon and firework-launching competition is the most prominent Tazaungdaing celebration in the nation; its origins can be traced back to 1894.

Tens of thousands of people come from all over the country to see highly decorated balloons launched into the night sky carrying tiers of fireworks as their payload. These fireworks are then set off to explode over (and frequently into) the crowd once they reach a safe (and more often an unsafe) height.

For the hospitality trade in the region, it is one of the busiest times of the year, and the winery restaurant was packed every single day of the festival, it was the perfect launching pad for Sharky’s Shomurice.

Ant Eaters

The Danu tribe are a recognized ethnic group by the government of Myanmar. They live mainly in the southern areas of Shan State, particularly around the Pindaya Caves. The name Danu derives from the Pali term meaning archer or bow, and is a reference to the legend of Prince Kumarabhaya. He is said to have rescued seven princesses when he used his bow and arrow to slay a giant spider that had trapped them inside the caves.

The Danu people forage and gather Sour Red Ants, which are used locally as an easily collected and inexpensive source of protein. Sharky, with characteristic mischief, soon had me eating them out of a jar!

When mixed with the rice for his Shomurice, the flavour, texture and hint of sourness gave the dish a definitive local character and unique lift.

Farm to Table

Sharky’s Shomurice uses 100% local ingredients: locally grown long grain rice, Pindaya sour ants, a blend of organic duck and chicken eggs, topped with a white velouté sauce, garnished with Shan chives and fried chive roots, and finely diced local tomatoes. U Ye is personally overseeing the cultivation of ten different heirloom varieties of tomatoes in the region. The dish is served with house-made, devilishly delicious, pickled Shan vegetables on the side.

The freshness and quality of the ingredients, the complexity of local flavours, combined with the silky-smooth textures of the egg and velouté are just remarkable, it is exquisite on the palate. The dish was an immediate hit with our Myanmar clientele, many of whom had travelled from across the nation to enjoy some of Shan State’s renowned local flavours. Many eggs-runs to the market took place over the ensuing days.

Of course, a big part of the attraction of this dish is the tableside performance of its creation. Just like the days of gueridon trolleys table side, Shomurice is a performance piece as well as a dish. The skill, technique, and experience, along with the flourish and personality of the chef, are all required to be on full display in order to bring the dish to life and give it full culinary expression.

Ever the performer, Sharky was in his element, enthralling guests with a mixture of skill, enthusiasm, good humour, and charm. Soon, every table wanted this wonderful human to share some of his glow and inner warmth with them, as well as his amazing food. In this regard, he is someone who possesses incredible reserves of energy along with a great depth of character, showing empathy, humility, and compassion. I feel deeply proud to call him my friend.

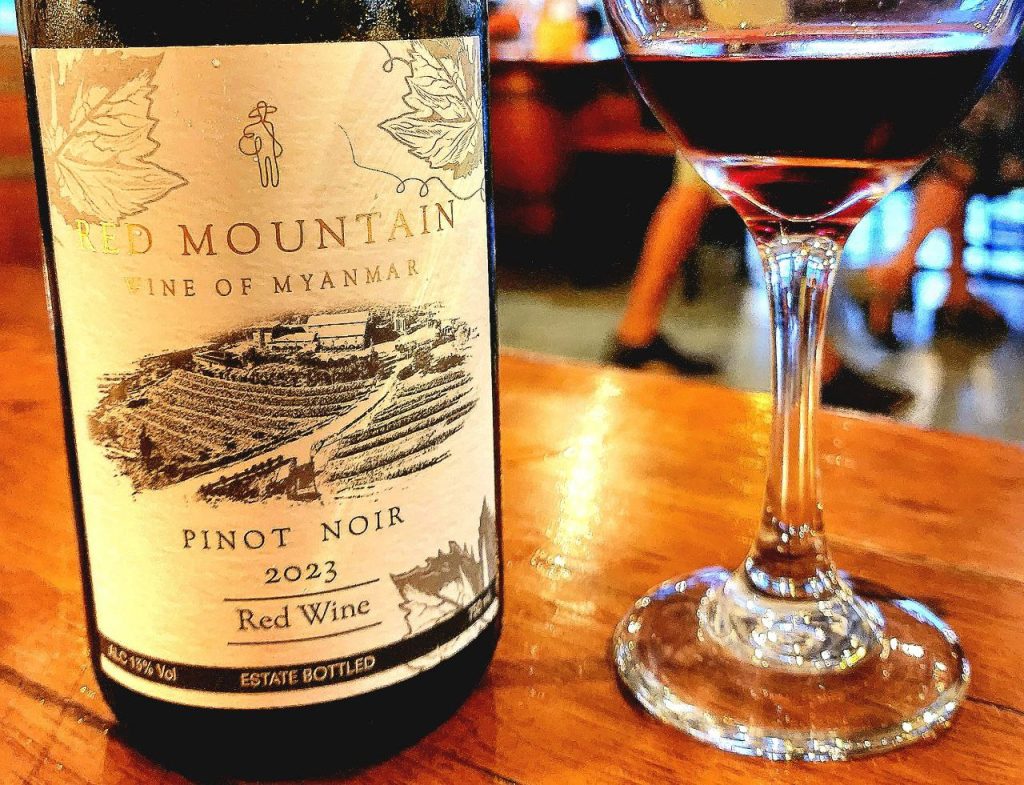

By the end of the week, Shomurice was the most popular dish on the menu, and the kitchen team were taking turns cooking it at the table of their many appreciative guests. It paired equally well with our Red Mountain 2023 Sauvignon Blanc for the white wine drinkers, and our Red Mountain 2023 Pinot Noir for red wine aficionados.

A new culinary sensation had been born from a love of fresh local produce and the vibrant diversity of Shan State’s flavours, people, and spirit.

Darren Gall