Goodbye La Maison

“We walk about under a load of memories which we long to share and somehow never can.”

― George Orwell, Burmese Days

La Maison Birmane

For ten to fourteen days of almost every month for the past five years, I have lived alone in my second home, La Maison Birmane, in the township of Nyaung Shwe, Shan State, Myanmar, down by Inle Lake.

A charming block of small, well-appointed wooden villas set in a burgeoning garden. The team there always looked after me so very well, always asking or offering to go that little bit further to make sure I was happy, comfortable and had all that I needed.

Some famous examples being when I once asked if they had anything like muesli for breakfast, I was quizzed on it, and then, when I turned up a month later, they had imported some from Thailand for me! I once (only in passing) mentioned that the bread in Nyaung Shwe was, for me, mostly terrible, and so, they started baking their own. I eventually learned this was just for me, only done when I was staying there!

As Covid and the coup took their toll on business, and international tourism dried up, I was pretty much the only one there most of the time. I was pleased that the Swiss-based couple who owned the place were keeping it open, especially as it kept their wonderful staff in a job.

The place was to me an island of peace and tranquillity, so quiet and calm in the middle of a country that was falling apart all around me. Here I could be contemplative, I could write, meditate, and just listen intently to my soul.

Ei Ei was the boss of Le Maison; she also lived on site and was as much a matron as a manager, caring for her team as well as her guests. A gifted and true hospitality professional whose career had taken her abroad to international hotels and included working on a private luxury yacht. Staying there was soon more than a pleasure; it became one of life’s small joys.

Ei Ei became the loving sister I never knew I needed or had. Ever charming, professional, warm, and always checking to make sure that everything possible was being done to enable me to enjoy my stay. She is an incredibly competent and personable lady, really a star at her job, and a friend that I will keep in touch with, but will miss deeply. I will miss them all.

Over the years, I would occasionally have dinners with Ei Ei and some of her team, where she would open up the long-closed restaurant to showcase their talent (and it was some of the very best food I have enjoyed in the region). They somehow always made me feel like it was as much a joy for them to cook for me, as it was for me to enjoy their delicious food and marvellous company. I would invite them to the winery for tours, tastings, food, and wine. When Ei Ei learned that my wife was pregnant, she sent me home bearing magnificent local gifts.

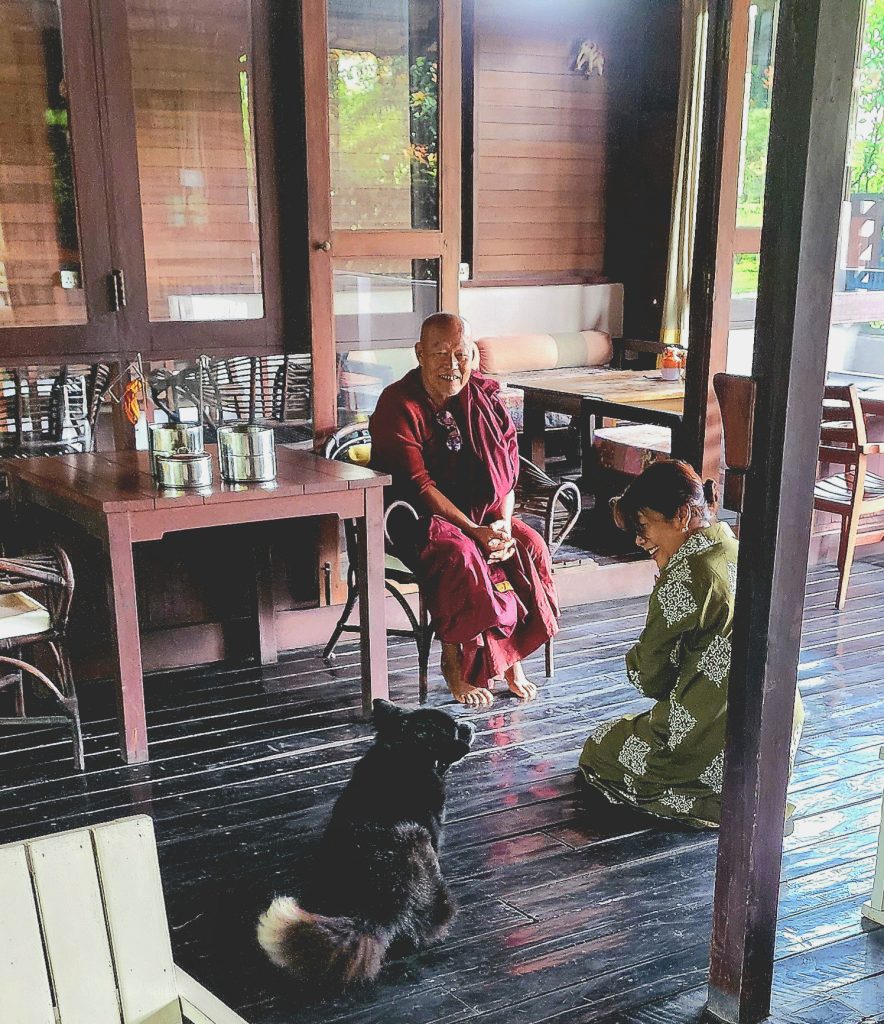

A couple of times a week, at around 7 am, our old local monk would arrive on an ancient motorcycle that looked like it was only being held together by wire and electrical cord. Looking aged, a little ragged, and yet also regal in his maroon robes, it always cheered me up to see him, smiling, calmly accepting merit (food) for the benefit of the sāvaka, gana and parisā. About once a week, the child nuns would come to the front door of the property, chanting blessings as they lined up single file to receive food and in turn allowing us to make merit. It was so cute, and it would set me off with a smile for the rest of the morning. Blackie the dog would lounge about, occasionally summoning enough energy to amble over for a pat.

When Ei Ei rang me on WhatsApp with the news that it was closing, I was not surprised; in fact, I was probably more surprised they held on as long as they did. Most resorts and hotels in the area have long since shut down, and almost all are available for sale on a market that no longer exists.

For years, the owners must have been losing money and praying for political change. They were obviously benevolent, keeping Ei Ei and the staff on for as long as they did. For that, I am eternally grateful to them, even though I have never met nor communicated with them.

I will miss La Maison Birmane enormously; it feels like being turfed out of your home and losing contact with some of your family members, all at the same time. I dropped in yesterday to say goodbye. Many of the staff had already left. Being so well-trained and good at their jobs, they have already found alternative employment.

Ei Ei was soon there, loading me up with things they had in their store, which were just for me: muesli, homemade jams, English tea bags, she had even baked some bread. With the few staff still left we took our last photos together, and as waves of profound sadness started to crash over me, I said goodbye to La Maison Birmane, my other home, for the very last time.

I don’t know where Ei Ei will end up, or what she will do now; wherever she goes, I know they will be damned lucky and soon grateful to have her. The same goes for the rest of her team, under Ei Ei’s leadership and training -and despite the incredible challenges they faced from pandemics to coups, to catastrophic floods, and a major earthquake- they always remained seamlessly and enthusiastically committed to their cause, providing exceptional hospitality for their guests.

My new second-home is just down the road. Ei Ei recommended it, went there (unasked) and scoped the place out to make sure it would suit me, and even negotiated a discount. It is remarkably similar in design and style, but it will not be the same. The food certainly isn’t as good. I will get used to it, I will settle in, eventually.

Somewhere inside, close to my heart, La Maison Birmane will always be a part of me, and I will always be looking out for my La Maison family, wishing them well and missing the way they cared for me and made me feel so at home.

In his 2022 book, ‘Grief: A Philosophical Guide’, the American philosopher Michael Cholbi separates grief from mourning, presenting grief as a process triggered by an acute disruption to our sense of oneself. The shock of loss, of disruption, forces us into recognising how much our values, commitments, and perception of the past and future are linked to that place, or person(s) we have lost. This sets us adrift, and we must contend with a new reality and a fractured sense of self.

He characterises grieving as an active process, not something that merely happens to us. While we can’t choose the emotions we experience, we can imbue them with meaning. For Cholbi, the inherent value in grief lies in its capability to expedite self-knowledge and the composition of a new self. In forcing us to contend with who we were in relation to our loss, and who we are now, grief can provide us with a unique and potent opportunity for self-understanding.

Michael Cholbi felt we had an “imperfect duty” to grieve, ingrained in a larger responsibility to pursue self-knowledge. This undertaking allows us to understand ourselves better and, in doing so, show respect for both ourselves and for our lost relationships.

Resolving grief involves including this loss in the story of our life, creating a “reformed practical identity”. It is not about getting over loss; it is learning how to make it an ultimately positive part of who we are.

I am enriched by my experiences in Myanmar. I have witnessed war, flood, earthquake, poverty and ruin, along with courage, hope, faith, resilience and a stoic determination; life finds a way. I will miss La Maison Birmane and the wonderful people there, but I will always be grateful for them having been a part of my life. I am forever made better by the people I met there and shared a part of my life with.

“This is Burma, and it will be unlike any land you know about.”

―Rudyard Kipling

Darren Gall