I noted with interest that a special 20th anniversary edition of John Ralston Saul’s jeremiad, ‘Voltaire’s Bastards’ had been released, a book that provoked in me a great deal of thought when I first read it, (ironically) almost twenty years ago.

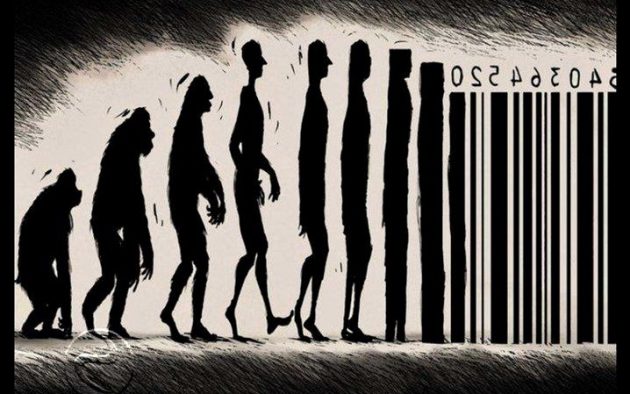

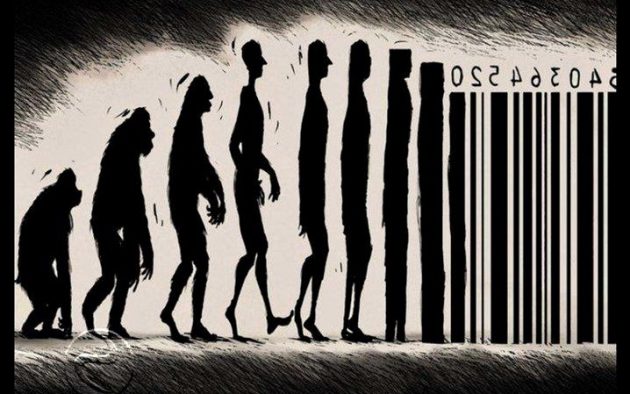

The tome is a sustained, agitated and sometimes aggressive tirade; a rant, an anatomy and a dissection of the evolution of humanism and modern rational society.

Saul asserts in this rousing polemic that whilst Voltaire, (1694 – 1778) had argued for reason as our last bastion against the arbitrary and corrupted power of monarchs and religion, it has evolved into a kind of mask from behind which the new, ruling elites are committing all manner of sins, abuses and crimes against the masses. In Saul’s view, we -the common people- are being duped.

Twenty years ago, the true nature of modern society was –as Saul’s saw it- ruled by a corrupt and disconnected corporatism which was mired in specialization, pretending to solve the world’s problems, only for these specialists to be the root cause and creators of much that ails the world.

A society where those at the top had little more than disdain for the rest of humankind and who justified their exploitation of the world’s resources to their own ends by using a brutal, clinical rationalism -hiding behind faux reason and flawed logic.

The book was written during the late 1980’s and early 1990’s, a time when corporate greed was considered to be at its all-time peak. A time when the world seemed to be ruled by stockbrokers and corporate moguls, masters of the universe traded on Wall Street and we started to see the true effects of globalization, where the leading brands were richer than most countries and where growth, profit and a healthy return to shareholders seemed to take precedence over empathy, compassion, equality, human rights almost everything else.

Saul foretold of a world where a ruling elite acted to serve only themselves and with increasing impunity, arguing that their decisions were based on logic and sound reasoning which made all of their decisions tough but fair, somewhat inevitable and for the long-term, greater good of all humankind. All this taking place whilst an increasingly disadvantaged, disenfranchised and disdainful population become progressively more disturbed, hostile and inevitably, revolutionary. Today, from Seattle to Syria and from Anonymous to extremists, we see revolutionary activity and outright revolution all over the globe and we can also see revolution in subtler ways, in our everyday lives, in the choices we make and in the voices we begin to listen to.

The industrial age brought many advantages and advances to the lives of our species; it has also had an increasingly dramatic impact on our atmosphere and our climate. At first, it slowly crept up on us, barely noticeable until, seemingly all of a sudden, there it was pollution, filthy pollution in all its forms, rubbish almost everywhere. The technological age enables us to see for ourselves, the damage we were doing.

Then, once again, it was all of a sudden almost overwhelming us and we began to understand that our own industriousness, our over-consumption, our over-production and our own greed, indeed the very things that some had argued made us great, also possessed the power to destroy us. Whether you subscribe to Adam Smith’s, (1723 – 1790) economic principles of productivity and benevolence or Karl Marx’s, (1818 – 1883) notions of corruption and exploitation; few then could have imagined our capacity to destroy an entire planet, like a cancer attacking its host.

The immensely successful 1982 film Blade Runner, directed by Ridley Scott and starring Harrison Ford was based on an obscure 1962 book of science fiction by the author Phillip K. Dick, (1928 – 1982) entitled ‘Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep’.

In this bleak, compelling piece of futuristic ‘automaton noir’ Dick describes a decaying, dystopian society being buried under the weight of its own industriousness and poisoned by its own ingenuity, we are being buried alive under the useless and discarded items of our own over manufacture, buried under ‘kibble’ as he termed it: everyday household goods that we had cast aside, were now swallowing up our homes, our cities, our planet, our lives.

Voltaire had believed that through sound thought and good reason man separated himself from all other living creatures and he held in great disdain matters of faith and the corruption of power from the ruling classes.

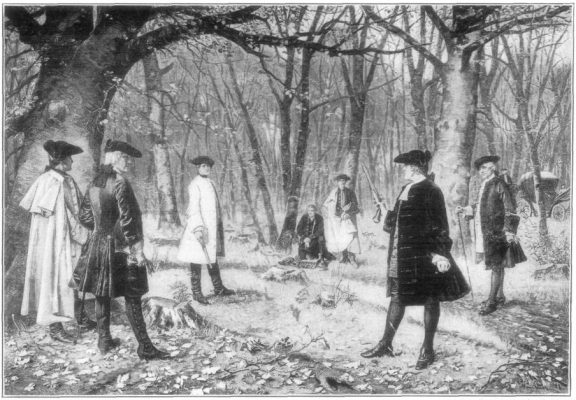

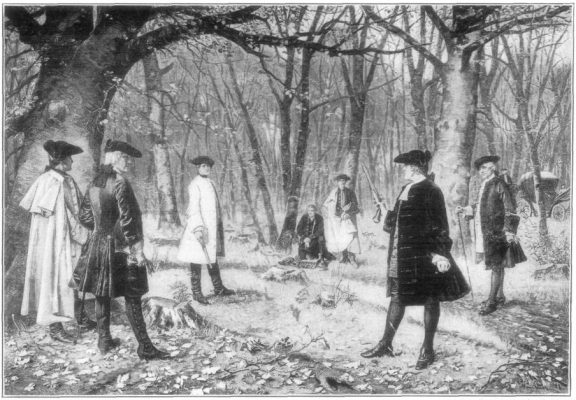

He used his pen as an epee and he wielded it with all the precision of a master swordsman in a fencing match or, as a surgeon with a lancet, performing open heart surgery.

His reasoning was his artillery; his wit, his bon mots and his put downs were legendary, often humorous, he dissected his opposition, taunted them, toyed with them. Voltaire’s particular cruelty was not to merely turn the tide of popular opinion against his opponents but, to have the people laugh at them with disdain, to humiliate them and in doing so, annihilate them. He once wrote that to hold a pen was to be at war.

Voltaire was not a man of mercy, yet some would say that Voltaire had good reason to terrorize the ruling classes of France in the early 1700’s. Born into a middle class family of little importance and a young writer struggling to make his name as a man of letters, Francois Marie Arouet as he was then known was beginning to gain a reputation as a bit of an upstart; a petty shit-stirrer amongst a court society used to considering it their privilege to do and get away with whatever they damn well pleased.

The young Arouet was an idealist who believed that rulers should be enlightened souls who protected the people’s rights and when he saw injustice he lashed out; his pen was indeed very sharp, soon he began to deeply offend and to gather serious enemies.

Voltaire was actually jailed for many a short spell in the Bastille for offending the nobility, the final straw came after he had traded insults with the aristocratic Guy Auguste de Rohan-Chabot known as the chevalier de Rohan and the comte de Chabot.

The Chevalier organized for Voltaire to be beaten in the street like a peasant whilst he watched from the comfort of his carriage, leaving the young writer busted up and bleeding in the gutter.

Voltaire was said to be incandescent with rage and began to prepare for a duel to the death, the Rohan family meanwhile, obtained a ‘lettre de cachet’ from King Louis XV and used this warrant to force Voltaire back into the Bastille and then into exile in Great Britain.

Francois Marie Arouet would relish his time in England and appreciate the philosophical and scientific breakthroughs taking place during this pre-industrial revolution period, a time of philosophical and scientific enlightenment in England. He returned to France, changed his name to Voltaire, still angry, still an agitator but now very much an enlightened one, few would ever again attempt to humiliate him.

Voltaire would spend three years in exile before returning to Paris, he then made a series of very sound business partnerships that would ultimately see him gain serious wealth. In 1733 he met and fell deeply in love with Emilie du Chatelet, (1706 – 1749) a woman twelve-years his junior but, with her own formidable intellect and determined, individual disposition. They would spend the next sixteen years together and form one of the great romantic and profound love affairs in all history.

Emilie du Chatelet was indeed a remarkable woman and one who made several great contributions to science, she had a profound influence on Voltaire, his thinking and his writing.

She was regarded as the first and only women of science and mathematics during her time in France, she published a novel criticizing Locke, which emphasized the need for knowledge to be empirical and verified through experience.

She published a paper on heat and light, predicting what is today known as infrared radiation

She wrote a paper titled ‘Lessons in Physics’ in which she attempted to reconcile complex ideas from some of the leading thinkers of the time.

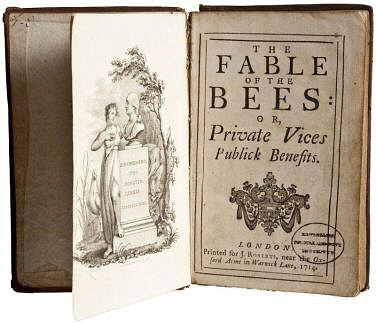

She translated Sir Isaac Newton’s ‘Principia Mathematica’ into French and then conducted experiments that were based on Gottfried Leibnitz’s theories on kinetic energy and velocity, counter to Newton’s theory. She published a critical analysis of the bible and she also translated the extraordinary poem by Bernard Manderville, (1679 – 1733) ‘The Fable of the Bees’ into French:

The poem was published in 1705, the book in 1714. The poem suggests such key principles of economic thought, as the division of labour and the “invisible hand”, seventy years before these concepts were elucidated by Adam Smith. Two centuries later, the noted economist John Maynard Keynes, (1883 – 1946) cited Mandeville to show that it was “no new thing to ascribe the evils of unemployment to the insufficiency of the propensity to consume”, a condition also known as the paradox of thrift, which was central to Keynes theory of effective demand.

However, at the time of publication the fable was considered scandalous. Keynes noted:

Mandeville gave great offense by this book, in which a cynical system of morality was made attractive by ingenious paradoxes.

In her preface to the translation, Emilie du Chatelet mounted a withering argument for women’s education. Chatelet also wrote a book on the nature of happiness, both in general and especially pertaining to women.

She is attributed with the following saying:

“Judge me for my own merits, or lack of them, but do not look upon me as a mere appendage to this great general or that great scholar, this star that shines at the court of France or that famed author. I am in my own right a whole person, responsible to myself alone for all that I am, all that I say, all that I do.

It may be that there are metaphysicians and philosophers whose learning is greater than mine, although I have not met them. Yet, they are but frail humans, too, and have their faults; so, when I add the sum total of my graces, I confess I am inferior to no one.”

‑‑‑Mme du Châtelet to Frederick the Great of Prussia, (1712 – 1786)

Voltaire and Emilie du Chatelet were indeed a formidable couple -one the voice of reason and the other the voice of science- questioning the old-world order in a new age of empiricism and enlightenment.

The central tenets of Voltaire’s philosophy where for enlightenment, for freedom of speech, freedom of the press, the right to assembly and freedom of religion:

All of which were largely denied to the common people in France at the time. He also argued for the right to oppose and question the capricious, cruelty of absolute rule and militarism and to oppose slavery -all of which normal practice during Voltaire’s lifetime were.

Voltaire believed that with good reason, with scientific analysis and with logic and common sense, we should be able to make better decisions about life, governance and beliefs and that rulers and monarchs should be surrounded by learned, incorruptible men, capable of free thought, to advise them, he believed strongly that this would make for a better, happier, more prosperous society as a whole. Although, later in life he seemed to abandon the idea of the enlightened monarch when he wrote at the end of his most enduring work, Candide, ‘It is up to us to cultivate our garden’.

Much of what Voltaire was arguing for at the time is taken for granted as true and correct today but, it was by no means acceptable to all of French society at the time and the outcomes of Voltaire’s debates, arguments and writings were not assured. He was railing against the Ancien Regime which involved an unfair balance of power and distribution of taxes between the three estates of the monarchy and its nobles, the clergy and then the commoners and middle class, who were burdened with most of the taxes and few of the benefits.

Along with being and advocate of the sciences and philosophies of the enlightenment movement of England that he encountered when in exile, he was also a great admirer of the philosophies of Confucius, (551 BC – 479 BC).

I may be no better, but at least I am different.

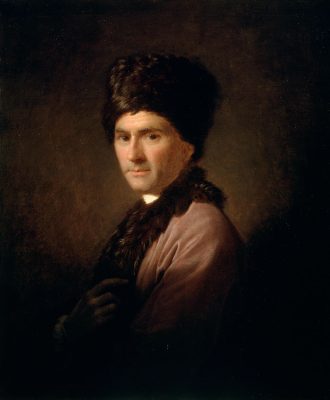

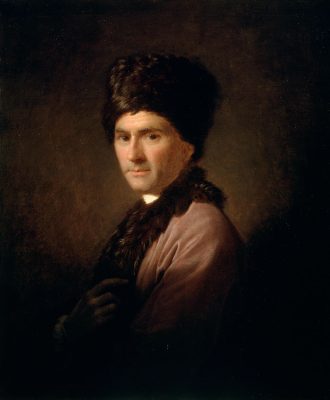

-Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Voltaire would have one legendary opponent in his lifetime and that opponent would have the name of one Jean Jacques Rousseau, (1712 – 1778) a formidable foe with romantic and somewhat wild theories for the way man should live.

Rousseau’s theories were attractive to many who felt the warring world of rulers, generals, priests and influencers of the 1700’s had lost the plot. Rousseau was advocating an entirely different solution to Voltaire and one that the French writer would find completely unpalatable.

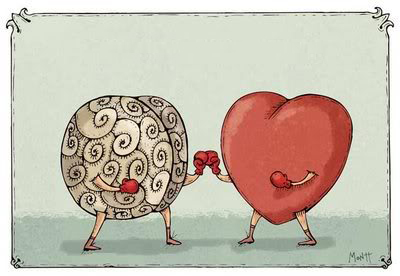

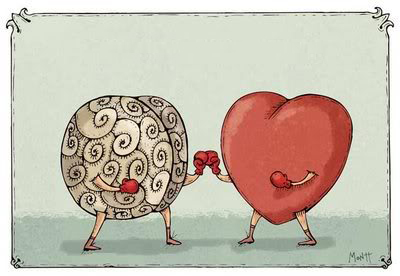

Where Voltaire believed that through education and reason we could separate ourselves from beasts, Rousseau argued that the way we went about these things was unnatural and corrupted us, he preached that we should get back to our natural state and live a more natural life, unconfused and at peace in the world.

Rousseau was, at least initially, influenced by the philosophies of Denis Diderot, (1713 – 1784) with whom he had spent much time reading. Diderot was a materialist, who believed in hereditary knowledge and rejected the benefit of empirical knowledge preached by Voltaire and others, Diderot felt that progress through greater physical knowledge lead man on a downward spiral of corruption.

Rousseau’s philosophy did not call for humankind to return to a state of stupid beasts but, he felt that we were entering a stage of corrupted civilization and the perfect state for human beings lay somewhere back from this evil evolution. He termed this state as the ‘Noble Savage’.

Against the philosophies of Hobbes, Rousseau argued that man in his basest, most natural state is essentially and instinctively good and that we must get back to this instinctive goodness which has been corrupted by reason and logic.

The heart was pure, the head wanted to lead it astray. Rousseau predicted that the more man deviated from his natural state in nature, the worse off he and his home would be.

Rousseau taught that we would be free, wise, and good in the state of nature and that instinct and emotion, when not distorted by civilization, are nature’s instructions to inner peace and the good life.

Rousseau was also considered a hero, having a great influence on the French Revolution which would take place barely a decade after his death. His most revered work is, ‘The Social Contract’ (1762) which outlines a government in a classical republicanism framework, which itself evolved from the political writings of philosophers such as Aristotle, (384 BC – 322 BC) Cicero, (107 BC – 44 BC) Machiavelli, (1469 – 1527) and Montesquieu, (1689 – 1755). He was an advocate of democracy and believed in a ‘general will’ that should be enforced by an elected government for the good of all, over and above any personal or private interest.

Rousseau saw a world full of decadence and corruption and held a deeply pessimistic view for the future unless we returned to nature and a more natural way of living.

It is easy to deride and criticize Rousseau, (as Voltaire did mercilessly) yet it is interesting to reconsider his views today in light of man’s negative impact on his environment and the frightening and increasingly likely implications of that impact on our future.

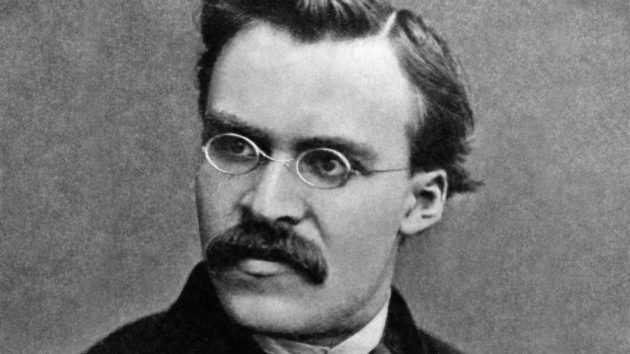

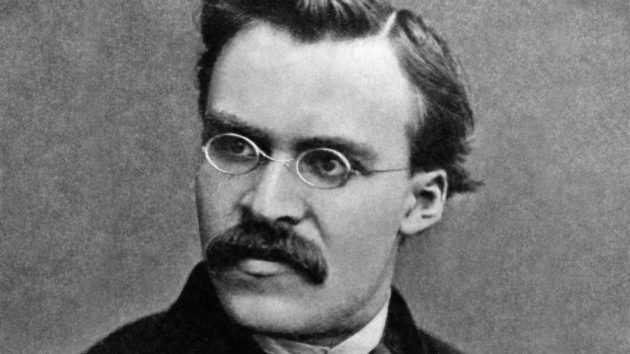

‘The Murder of God’, is what Friedrich Nietzsche accused man of in his book The Gay Science, (1882) the passage reads:

‘God is dead. God remains dead. And we have killed him. How shall we comfort ourselves, the murderers of all murderers? What was holiest and mightiest of all that the world has yet owned has bled to death under our knives: who will wipe this blood off us?

What water is there for us to clean ourselves? What festivals of atonement, what sacred games shall we have to invent? Is not the greatness of this deed too great for us? Must we ourselves not become gods simply to appear worthy of it?’

— Nietzsche, The Gay Science, Section 125, tr. Walter Kaufmann

What Nietzsche was referring to was not the actual death of god of course, he was referring to what he saw as the Christian God as no longer being a credible source of absolute moral principles.

We abandoned God as our moral guide and now Nietzsche understood that God would have to be replaced, for if he were not then we might find ourselves living in a world of total anarchy and chaos. Just who or what we might choose to replace God as out moral compass would be just as telling towards our future as a species and continues to be a source of great interest and influence today.

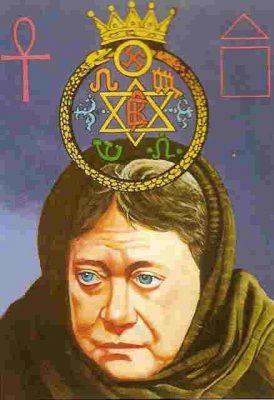

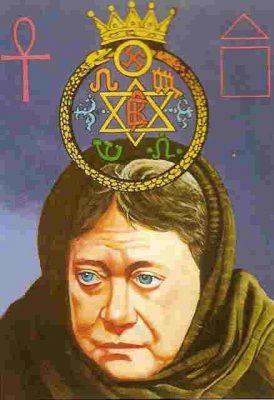

Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, (1831 – 1891) is a woman with a very shadowy background and an upbringing riddled with conflicting stories, events and dates. Said to be born to Russian-German aristocracy and widely travelled, she was an occultist, a spirit medium an author and a co-founder of the Theosophical Society in 1875.

According to her own narrative she embarked on a profound journey in 1849 which included an encounter with a group of spiritual adepts she calls the ‘Masters of Ancient Wisdom’.

The journey took her to Africa, the Orient, throughout India and to the South Americas continuing her spiritual education from different gurus, most notably the mysterious Master Morya and Mahatma Koot Hoomi.

She claimed that these masters had a number of astounding abilities which included clairvoyance, clairaudience, telepathy, the ability to control another’s consciousness to de and re materialize and to project astral bodies. Ultimately, she was instructed to travel to Shigatse in Tibet where she was trained to develop her own psychic powers and where she claims to have learned the unknown language of Senzar, translating several ancient texts that had been preserved in a nearby monastery by Tibetan monks.

Blavatsky was the leading theoretician of the Theosophical Society which she founded in New York in 1875 with her colleagues, Henry Steel Olcott and William Quan Judge. Theosophy combines two Greek words, Theos and Sophia which mean divinity and wisdom. The name of the society describes a broad system of esotericism, referring to a lost and hidden knowledge of a spiritual nature that explains a connection between the universe, human beings and divinity, and reveals their origins.

The Theosophical Society’s doctrines made references to Buddhism, Hinduism, Theism, Spiritualism, Cosmology, Hermeticism and Occultism.

H. P. Blavatsky was nothing if not a polarizing figure, some idolized her as a divine guru with psychic powers and others detested her, derided her and treated her with complete and disdain seeing has as a contemptible charlatan and trickster.

Many people attempted to discredit Blavatsky, both during and beyond her lifetime, several have managed this with success yet, it is interesting to note that the Society still operates today in over fifty countries around the world and many have suggested that Blavatsky opened the pathway to the modern New Age movement of today.

In essence the main aims of her society where honed down to be as follows:

To form a nucleus of the Universal Brotherhood of Humanity, without distinction of race, creed, sex, caste, or colour.

To encourage the study of Comparative Religion, Philosophy, and Science.

To investigate the unexplained laws of Nature and the powers latent in man.

At the time that Madam Blavatsky was making a name for herself as a medium and spiritualist, Europe and much of the western world was a place dominated by industrialism, the sciences and a practical rationalism that was clinical, cold and brutal to some and lacked a sense of ethereal warmth and compassion to many. This understanding of the universe did not rely on faith, it required education and had a capacity to be exclusionist and exploitative.

Here was also an elite society, one who largely believed that much of the world’s great mysteries had been solved thanks to people like noted mathematician and alchemist Sir Isaac Newton, (1642 – 1727) and Gottfried Leibniz, (1646 – 1716) and men of their ilk. Isaac Newton published his magnum opus: Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica and simultaneously with Leibniz discovered calculus.

Newton, in discovering universal gravity, the laws of motion and classical mechanics had demonstrated that a universe created by god was like an infinitely large precision instrument like a watch for example, the once he had wound up would tic along nicely under its own steam.

Leibniz is considered one of the world’s greatest ever mathematicians, he is credited with independently discovering calculus simultaneously at the same time as Newton, although many argue his version superior. He is also credited with refining the binary system which is today the foundation of virtually all digital computers.

These men had discovered a framework by which soon the final pieces of the jigsaw puzzle would be uncovered and all the secrets of the universe would be revealed, all understanding of god’s plan rendered simple and all knowledge discovered.

However, this was the world of the ruling classes, the elite and the exceptionally well educated, it was not the world of the working class and the commoners, it was not the world of the masses who were yet to grasp this new found practical science and who still relied on superstition, faith and beliefs and who needed perhaps above all else, to be given hope.

By the time of the formation of the Theosophical Society, still these answers to the final great questions of science had not come.

Common people were beginning to wonder if we’d not gone down the wrong path entirely and forgotten some lost and ancient wisdom that would reconnect us to the universe and comfort us instead of reducing it to impenetrable mathematical code and cold hard mechanics.

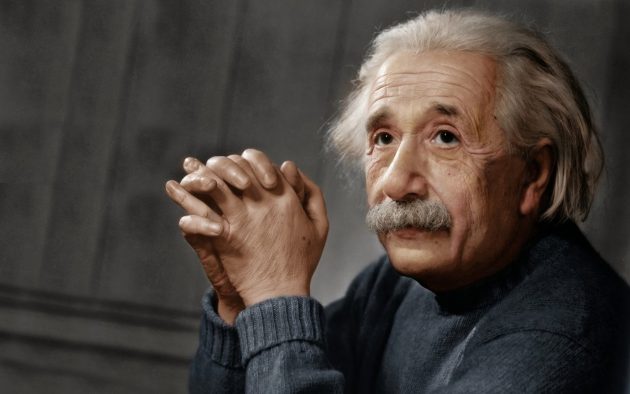

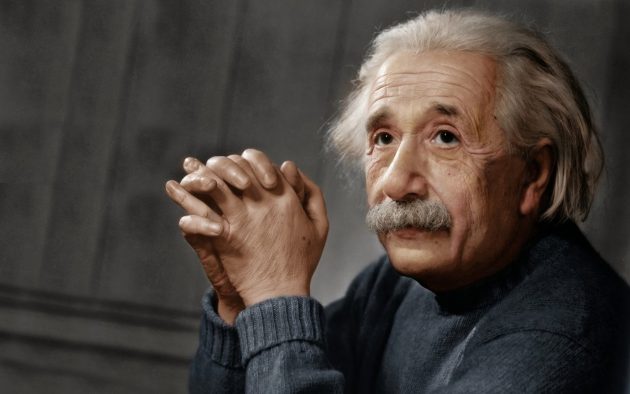

After nearly two hundred and fifty years, a young patent clerk by the name of Albert Einstein, (1879 – 1955) would prove to the world that Newton -whilst having made some wonderful and extremely important discoveries and who was someone that was indeed, rightfully regarded as one of the greatest scientist whom ever lived- was also quite wrong.

With his ‘General’ and then later ‘Special Theory’ of relativity, Einstein was able to show us that the universe -far from being set up something like a Swiss Clock with an energy that never ran down- was a universe where things like matter, energy and light, where relative and changeable in relation to the viewer. What Einstein showed us was that the very world as we knew it was relative to the viewer and that gravity had the power to bend space, light and time.

E=MC2, this simple equation would turn man’s understanding of the universe and Newtonian Mechanics on its head, yet this equation was so complicated that few understood, let alone accepted it at the time. Max Planck, (1858 –1947) was a theoretical physicist who originated quantum theory, which won him the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1918, he was amongst the first to realize the importance of Einstein’s theory and bring it to the full attention of the scientific world.

For the record, the equation is a way to state that energy is the equivalent measure to a particular body of mass plus all of the latent or potential energy within it. So difficult was this for people to understand at the time that Einstein was constantly stopped by strangers in the street and asked to explain it, he ended up refining his response to a simple, “Pardon me, sorry, always I am mistaken for Professor Einstein.”

The theosophy of H. P. Blavatsky provided some modicum of spiritual comfort to many but, it lacked a grounding in the physical world, a tangible and practical connection to the common and the commoner. Enter an extraordinary individual by the name of Rudolf Steiner, (1861 – 1925) an Austrian who was part mystic, part philosopher, part esotericist and also an artist, an architect and a literary critic.

Anthroposophy, according to the latest edition of the encyclopaedia Britannica: is a philosophy based on the premise that the human intellect has the ability to contact spiritual worlds. It was formulated by Rudolf Steiner, who postulated the existence of a spiritual world comprehensible to pure thought but fully accessible only to the faculties of knowledge latent in all humans.

He regarded human beings as having originally participated in the spiritual processes of the world through a dreamlike consciousness.

Because Steiner claimed that an enhanced consciousness can again perceive spiritual worlds, he attempted to develop a faculty for spiritual perception independent of the senses. Toward this end, he founded the Anthroposophical Society in 1912. The society is now headquartered in Dornach, Switzerland and has many branches around the world.

Immanuel Kant, (1724 – 1804) is a giant of philosophy who founded a Kantian movement known as ‘German Idealism’, based on his philosophical investigations and critiques, this movement spawned a list of eminent disciples such as Fichte, Hegel and Schelling and still today, Kant is considered a central figure in modern philosophy.

Kant’s major work was his ‘Critique of Pure Reason’ in which he attempted to explain the relationship between reason and the human experience, moving beyond what he saw as the inability and ineptitude of exiting philosophy and metaphysics. Kant created a duality where there is both the real world, which we cannot know of in itself and there is the world as we arrest it with our senses and process a representation of in our minds.

What he was saying is, we create an imagined world in our mind based on what we see, smell, hear, touch and taste. So, when we see a tree in a field, it is not the actual tree we are seeing but our mind’s mental representation of what our eyes have captured and this is not the thing in and of itself, it is an image of that thing inside our head and created by our own brain.

We do not really know if this is how the tree actually is outside of our brain; we may discuss it with others and form a view that we all see something similar but, if one of us is colour-blind and the other only has sight in one eye, then our views on how the tree really is in the world will be very different from each other.

Kant believed in certain types of knowledge, a posteriori knowledge and a priori knowledge, the former being knowledge gained empirically and the second being gained without any experience. Kant argued that for synthetic judgments to be made they required a foundation of certain a priori conditions to apply, namely time and space. However, he said that fundamentally we could not know of the world beyond that observed with our senses and embellished with our reason, to go beyond this and into the realm that we cannot empirically observe requires us to embark on what Kant termed an ‘adventure of reason’.

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749 –1832) was a German statesman, writer and poet of immense standing and influence in his society, his most enduring work is his epic Faust, yet Goethe was also something of a scientist and like just about everything else he turned his attention to, his contributions would be not only well respected, they would be very important indeed.

Sturm und Drang, (Storm and Stress) was a proto-romantic artistic and literary movement in Germany during the late 1700’s, it promoted freedom of expression and especially extremes of emotion in art, it was seen as a direct reaction to the constraints of the rationalism imposed by The Enlightenment movement. Goethe was an early advocate and member of the movement.

Goethe determined to embark on his own ‘adventure of reason’ and turned his attention to botany and what he saw as a problem with the Cartesian-Newtonian Science practiced at the time. Goethe believed that a science where only the physical, material characteristics and only selected external traits were considered, led to a widening gulf between man and nature and we were increasingly worse off for it.

Goethe felt that observation and experimentation had to be more about immersing oneself in nature and less about extracting physical objects from nature and observing them in isolation. Goethe was truly a remarkable individual his science wanted to show us that in immersing ourselves in nature and in considering the change over time we would learn not only about our subject but also about ourselves.

Where Cartesian-Newtonian science accepts only a single, practical syllogism regarding the experimenter and the topic, Goethe demonstrated and believed in a science that was also an artistic practice, as much about refining the experimenter’s perceptions over time towards inspiration, imagination and creativity.

Goethe seems to have sought to bring reason back into the fold of nature and connect or reconnect the two. It is easy to be flippant about Goethe’s vision for epistemology but, it seems to me that he was sensing that in looking at things outside of nature we were isolating ourselves from nature, from the world we lived in and we were increasingly diminished for it. He could see that the accepted norms of knowledge as the accumulation of facts were creating divisions between the science and culture of his day. Goethe saw knowledge as an observation of organic progression in nature and over time also being the inner transformation of the experimenters themselves.

He was interested in not only what we had learned but also in how it had changed us. For Goethe our gaining of and responses to knowledge needed to be undertaken with empathy and compassion and needed to be shared in such a way as to be understandable.

One of the topics Goethe was getting at, particularly in his ‘Story of My Botanical Studies’ was a notion that not all things were created exactly as they were but, that they adapted over time, they ‘evolved’. His work only suggests these observations over time however; the book was published almost thirty years before Charles Darwin’s epic, ‘On the Origins of Species’.

So to reprise: What Goethe was proposing, was a way to look at things inside nature and to include ourselves inside the circle of nature, include time and experience and our own ability to learn and change from this very way of learning. He saw this as a thing of beauty and of man in nature and connected to his universe.

Goethe was an inspiring character, a giant of his age, his artistic writings inspired works by the likes of Mozart, Mahler and Beethoven.

His scientific work influenced many, the artist J. M. W. Turner was inspired by Goethe’s work on the colour spectrum as was the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein, who wrote his ‘Remarks on Colour’ in response to Goethe’s ‘Theory of Colours’, (1810) whilst he was dying of cancer in 1950 and 1951.

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, (1770 – 1831) was greatly inspired by Goethe’s theories on learning and applied them to his philosophy and Arthur Schopenhauer, (1788 –1860) sought to expand on Goethe’s theories during his philosophical career. Friedrich Nietzsche, (1844 – 1900) wrote glowingly of Goethe in his work, ‘Twilight of the Idols’ (1895).

Nikolai Tesla was an ardent fan of Faust and the Disney Film ‘Fantasia’, (1940) features a popular section with Mickey Mouse, known as ‘The Sorcerer’s Apprentice’ which closely follows Goethe’s poem of the same name.

Psychiatrist, Carl Jung (1875 – 1961) acknowledged the profound effect Goethe had on his thinking, stating that Goethe was his pre-eminent spiritual ancestor.

Perhaps the person whom Goethe had the greatest influence on of all was Rudolf Steiner, who was so informed, inspired, moved and indebted to Goethe that he designed and built not one, (in 1913) but two buildings, (after the first was burned to the ground in 1922) dedicated to the man, naming them ‘The Goetheanum’. Both buildings were and are still considered masterpieces of architecture and the second structure is still in use and opens to the public every day, in Dornach, Switzerland.

Steiner is considered the father of Biodynamic agriculture, a regimen widely practiced today and lauded by some of the most highly regarded and sought-after wines in the world.

The issues raised by Ralston Saul, Rousseau, Goethe and others are valid today, we can reason away anything if it does not suit our ends and we can find reasons to justify serving any of our most base human desires. It is as if, for some of us, reason has become a flaw in our machinery designed to trick out utility, empathy and compassion in order to feed the unquenchable fires of our will to personal strength and power and take us further from interconnectedness and our place in nature, the universe, our chi and the transcendental entanglement of being.