“The meaning of life is to find your gift. The purpose of life is to give it away.”

― Pablo Picasso

What commonly happens in the restaurant is that a guest will take command of the wine list, select a wine that they personally like, without much thought of the food or company, beyond perhaps seeking cursory approval from the table, more often than not friends will simply nod and agree. Wine chosen; great now we can quickly get on with the important stuff –comparing Trip Advisor notes, checking in on social media and taking a few selfies.

To be honest, I don‘t see anything wrong with that if all you are looking for is good friends, good food, good wine and a good time, go for it, enjoy yourselves and have fun.

Sometimes there is more to be sought and much, much more to be enjoyed if it is your wish to pursue dining experiences that your senses can discover, marvel at and enjoy in much the same way your eyes and ears, neural synapses and limbic resonances are affected by great works of art or great performances, be that perhaps a painting, a piece of music, a play, an opera, even an epic movie.

I remember when the artist Marina Abramovic was performing “The Artist Is Present,” a piece where she invited strangers to sit across from her at a table for as long as they wished. She would sit silently for up to seven hours a day whilst all these anonymous strangers would come and sit opposite her.

Unknown to Marina was that her former lover Ulay was in attendance on the opening day, the pair had an intense love affair in the 1970’s, performing together and living out of a van. When they decided to part they did it with a gesture, each starting at one end of the Great Wall of China and meeting in the middle for one last embrace; it was the last time they would see each other for thirty years. On this day, Ulay patiently waited in line and when his turn came strode to the little table and sat opposite the love of his life. What happened next was something so magical, so emotional and so moving that it is beyond description. Whenever I see this piece of film two things are inevitable, I shudder with my whole body and my eyes well up with tears. Life and art converged at that moment and it was both a small thing and a big thing and a thing of immense beauty, a thing that seemed to transcend all the universes and set our reality quivering like the surface of an immense pond which had just had a tiny pebble tossed into the middle of it.

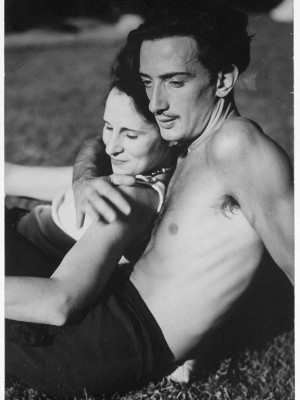

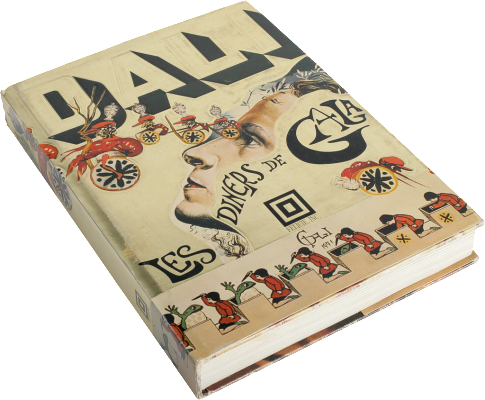

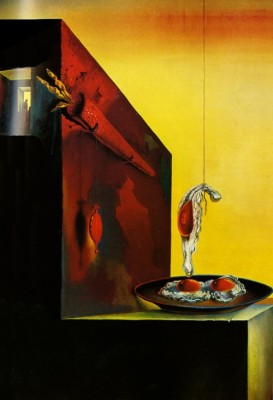

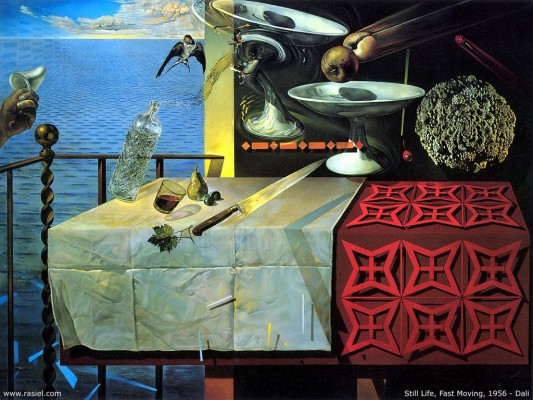

The great surrealist artist Salvador Dali (1904 – 1989), is one of the most profoundly gifted, controversial and exquisite artists of all time. In 1924 he met his muse, the love of his life, Gala. So completely in love with Gala was the young Dali that he wanted to devour her, believing that by ingesting his lover he would get to truly experience her soul. He painted her with lamb chops on her shoulders instead, he painted two lovers consuming each other and called it Autumnal Cannibalism in 1936, just two years after they were married. Dali resisted the urge to devour his wife, eventually releasing a surrealist’s cook book in 1973 with his wife on the cover.

Aestheticism is a branch of philosophy that involves an understanding of the nature of art, beauty and what might be called taste. When we engage our senses with a work of art that work can confront us, challenge us, move us and most often it ultimately pleases us. Philosophers from the Ancient Greeks like Plato and Aristotle through to empiricists, the enlightenment, romantics and existentialists such as Hegel, Schopenhauer and Nietzsche, all have written extensively about Aesthetics and today, modern philosophers continue to do so. What makes something beautiful to us? What is beauty and how do we define it? Why does it affect us so and how do we determine what is worthy of being called art?

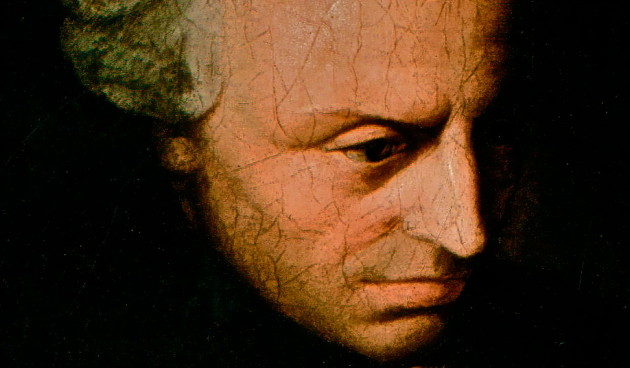

The great philosopher Emanuel Kant in his ‘Critique of Judgment’ (1790) called aesthetic judgments, ‘judgments of taste’ going on to state that: ‘Aesthetic pleasure comes from the free play between the imagination and understanding when perceiving an object’. Kant distinguishes the beautiful from the sublime: ‘while the appeal of beautiful objects is immediately apparent, the sublime holds an air of mystery and ineffability’.

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe believed that the fundamental nature of the world was aesthetic and once stated “There is nothing worse than imagination without taste”. Friedrich Nietzsche felt that ‘for art to exist, for any sort of aesthetic activity to exist, a certain physiological precondition is indispensable: intoxication’. Artists such as Oscar Wilde and Baudelaire were greatly preoccupied with Aestheticism as a way of life and are credited with starting an Aesthetic movement; ‘Art for Art’s Sake’ was their mantra.

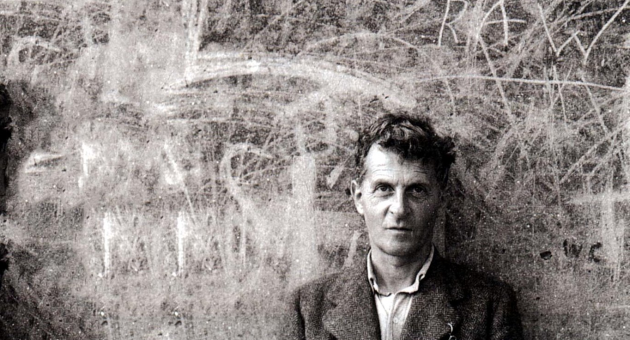

Ludwig Wittgenstein, (1889 – 1951) is said to have possessed one of the most intelligent, gifted and innovative minds throughout all of philosophy. His father, Moses Meier Wittgenstein was an industrial tycoon who made them the second wealthiest family in Austro-Hungary behind the Rothschilds of Banking and Winemaking fame. Moses had eleven children, five of them boys, Ludwig’s sister, Margaret was painted in a magnificent portrait by no less than world renowned artist Gustav Klimt, (Klimt’s ‘Kiss’ being one of the most widely recognizable paintings in the world today).

All of the children were educated at home -lest they pick up bad habits at school- all of the boys were being prepared to be captains of industry although one, Hans was considered a gifted musical prodigy, sadly three of the five boys would commit suicide.

The eminent Cambridge Professor, Bertrand Russell called his young student, Ludwig Wittgenstein, “the most perfect example I have ever known of genius as traditionally conceived; passionate, profound, intense, and dominating”. A few years later, Wittgenstein criticised a piece of his professor’s work, of the criticism Russell wrote, “(tho) I don’t think he realized it at the time, was an event of first-rate importance in my life, and affected everything I have done since. I saw that he was right, and I saw that I could not hope ever again to do fundamental work in philosophy.” When Wittgenstein returned to Cambridge in 1929, John Maynard Keynes wrote in a letter to his wife, “Well, God has arrived. I met him on the 5.15 train.”

During the ‘Great War’, (World War 1, 1914 – 1918), Ludwig Wittgenstein spent his time -as a soldier and later as a prisoner of war- writing his magnum opus. This, in the end turned out to be a rather slim 75 page philosophical treatise, the only book of his writing that would be published in his lifetime.

The Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus is legendary in philosophical circles for the incredible austerity and economy of its writing and for the sheer ambition of its subject, which was no less than to identify the relationship between language and reality and to define the very limits of science. Upon the books release Wittgenstein promptly concluded that he had now resolved ALL philosophical problems.

When he would somewhat reluctantly meet with the Vienna Circle he was said to have preferred to face the wall and recite the poetry of Rabindranath Tagore, instead of indulging in any of the philosophical discussions the circle was noted for.

In one of the finest interpretations of the book, authors Janik and Toulmin, (Wittgenstein’s Vienna, 1973) assert that the Tractatus assigns a central importance in human life to art, on the grounds that art alone can express the meaning of life. Only art can express moral truth, and only the artist can teach the things that matter most in life (Janik & Toulmin, 1973: 197).

All this talk about what is good art and what is beautiful and we reduce it to a question of taste. Oscar Wilde put it perhaps most succinctly when he quipped “I am a man of simple tastes, I am always satisfied by the best.” A most interesting term when you consider that as a sense, it would appear to be the one we utilize the least when assessing works of art but, employ the most when called to describe it.

Without expanding into a discussion on taste in sociology and sticking with food consumption in particular: for all its uses to describe works of art, fashion, behaviour and more; gustation is just not generally considered a valid means of appreciating an art form. Yet, more and more, we are seeing organoleptic properties in cuisine that could very easily be described as imaginative, creative, crafted and artistic; these dishes and degustations -it could be argued- possess properties that perhaps could only be described as having a great deal of good taste.

Aside from instinctive or behavioral knowledge related to genetic memory, everything we know and everything we learn comes to us through our senses, it is how we experience being and existing, it forms the basis for everything we know about the world we live in.

Much of art is designed for and is appreciated by the eyes and the ears -this is understandable as we gain spacial awareness from these senses- much less so by our other senses, (touch, smell, taste) in aesthetics these are sometimes called the lesser senses. Yet these are powerful tools indeed.

The human olfactory system, our sense of smell and the mechanism for transferring aroma information to the brain, can store and recall at least 10,000 different odours. A recent study conducted by a research team headed by Dr. Andreas Keller at Rockefeller University and published in the Journal of Science in 2014, suggests that figure could actually be as high as the impossible figure of 1 trillion!

Our sense of smell is also the only sense we have that plugs directly into our memory, where all others take a more circular route through the brain to arrive at memory. Our smell memories are pure unadulterated memories. We have an ability to store all of these smell memories from our childhood, carrying them with us for the rest of our lives; these smell memories that taught us things and shaped who we are and can be extremely discriminating and discerning.

If we understand something we are said to have grasped it, as in grasped the idea of it, if something is deemed in good condition we say it is in ‘fine touch’. Our sense of touch is actually more than a single sense it is a system, the somatosensory system to be exact, which consists of a number of different receptors.

Tactile sensations are some of the most intimate and powerful experiences of the outside world, the physical world we will ever have, if something moves us deeply, such as a romantic film, we say it was touching, or it touched our hearts, we are deeply touched by things. When we describe our emotions we say we are describing our feelings, when we touch something or someone we say we are feeling it or them, when we begin to like something we say we are ‘getting a feeling for it’ when we are falling in love we say we are developing ‘feelings’ for someone and so it seems, we can have feelings both on the outside and on the inside as well.

Finally, we come back to taste, or are we talking about flavour? The flavour of things; what are we really talking about when we pop things into our mouths, when we consume them, when we ingest them for our inner workings to extract their essence?

Flavour is generally regarded as the experience of a thing as derived purely on the tongue, whilst the taste of a thing is regarded as a combination of sensory tools experiencing the qualia: flavour, olfactory sensation, (both nasally and retro-nasally) the texture and feel, the weight or body of a thing in the mouth, aftertaste sensations and sensations of taste along the epiglottis in essence, a combination of olfactory and in-mouth sensations are required to get the true ‘taste’ of a thing.

The Psychophysics of Taste, a German research paper written by D. P. Hanig in 1901, set out to map the human tongue showing which flavours were picked up by which different parts of our muscular hydrostats.

When Harvard psychologist, Edwin G. Boring translated the paper, the data became widely known, popular and generally accepted as fact. Still today, this map of taste across the tongue is widely known and is still in common use.

The map showed that we taste sweetness at the front of the tongue, bitterness at the back, salty and sour flavours along the sides. Later on an additional taste, Umami was added by Japanese Professor Kikunae Ikeda, umami is a pleasant savouriness derived from glutamates. However, much of the original paper was misunderstood or misinterpreted, leading to a great deal of confusion and misconception about how the tongue conveys the qualia of taste. Much of the perceived assumptions about the paper have now been debunked by additional research and experimentation which suggests that our receptors on the tongue can pick up any identifiable flavours such as sweet, sour, bitter, salty, savoury or umami across all parts of the tongue and that it is our brain which deciphers which flavour data is which. Yet, perhaps because my own brain has been preconditioned, whenever I taste and actively try to perceive these tastes on my tongue, I am consciously aware that where the five tastes are strongest on my palate corresponds with the old thinking and the old map not entirely but, certainly to the point where it is as I perceive it.

In-mouth-sensations and retro-nasal olfaction also play a massive part in our perception of taste. How a wine ‘feels’ in our mouth is both interesting and important to overall qualitative and enjoyments perceptions, mouth-feel relates to the weight of the wine, literally how heavy does the wine feel on the palate, the width of flavour across the palate, the length of flavour along the palate and the overall texture of the wine as it passes across the palate and down over the epiglottis.

Aftertaste resonance is also a significant factor in adjudging overall flavour and taste of a wine, within a second or two of swallowing a mouthful of wine the fruit flavours will re-emerge in the taste receptors and linger for a short or sometimes a long time. In this way we are using three senses in the mouth to asses flavour: taste touch and smell.

One Person’s Nepenthe is Another’s Poison

Back to Immanuel Kant was said to be a man whose routines were so precise that locals could set their watches by them. He always took lunch at a local restaurant in Konigsberg at one, eating and drinking wine heartily, occasionally he was said to have consumed enough wine to forget his way home. In his monumental Critique of Pure Reason (1781), Kant postulated that we can never really know a ‘thing in itself’ we can only know of a thing what we experience of it with our individual senses.

This is where language and social interaction become important, we use language to convey and receive notions from others that may then help us determine if what we have perceived is the same, or similar to what others have perceived of an object or event.

Yet, as we well know, words often fail us.

Using the English language in all its forms and variations think of the available lexicon to specifically describe smells and tastes, one quickly realizes that there is an extremely limited vocabulary at one’s disposal. We simply do not have that many words to describe the myriad of tastes and especially smells that we are subjected to. How many specific ‘smell’ words can you quickly write down? Not that many is there?

One of the main reasons for this phenomenon comes down to what is going on in our heads when we smell and taste. Much of the sensations derived from assessing wine are smell derived so let’s go back to our sense of smell for a moment; the nose is an incredibly talented and underutilized tool, it is believed that humans have the ability to store and discriminate between thousands of different odours in memory.

To very simply describe some rather complex biology: when odour molecules enter the nose they are picked up by receptors in the olfactory bulb located high in the nasal cavity, signals created by these receptors are transferred along the olfactory nerve to the brain where they are recognized as a particular odour. Many perceived flavour sensations are also really smell sensations because they are picked up by the olfactory bulb retro-nasally whilst the wine is in the mouth.

The olfactory blub reports on these smells directly into the limbic system of the brain, this is sometimes referred to as the old brain or the mammalian brain, a small section of the brain housed deep within the familiar grey-matter image we all know. This is the oldest part of the human brain in an evolutionary sense, it is the part of the brain that communicates with the rest of the body through the release of chemicals, governing our body temperature, our moods, our physical and instinctive reactions, our behaviour and it is where we store our memories. This is where terms like ‘the smell of fear’, ‘the smell of victory’ and ‘the smell of home sweet home’ can begin to make sense to us.

In countless wine classes I’ve conducted for professionals and amateurs alike, the most common difficulty tasters face is not in assessing the wine but in describing what they are tasting and smelling, finding the right words to convey their sensory observations.

When people do ‘find’ the language to describe what they are smelling in a wine, they often describe a childhood memory such as smelling the oak in a wooded wine and describing it as ‘like their grandfathers woodwork shop’ or smelling a citrus quality in a wine and describing it as ‘the old lemon tree in their parents backyard’, whilst not being able to find a word to describe exactly what they are smelling, they are able to recall and describe a memory of that odour.

Finding the right words can be difficult because we develop language in a completely different and far more recent development of the human brain, the neo-cortex. This is the area of the brain where logical thought happens, where we use reason and logic to solve problems and make decisions. It is interesting to note that these two different parts of the brain, (the limbic system and the neo-cortex) often appear to be in conflict with each other; this is where terms like ‘head over heart’ and ‘mind of matter’ begin to make sense.

This shows that our sense of smell and taste is governed by a much more primal and instinctive part of the human brain, one where there was no need for language and no ability to develop it -that came much later in human evolution.

In Wittgenstein ‘s ‘Tractacus Logico-Philisophicus’, he suggests that language was like painting a picture and he then attempted to define that of which we could and could not speak. Wittgenstein concluded that with the Tractatus he had resolved all philosophical problems, and upon its publication he retired: according to an end of the century poll, professional philosophers in Canada and the U.S. ranked it as one of the five most important books in twentieth century philosophy. However, later in his life and published posthumously, Wittgenstein’s ‘Philosophical Investigations’ all but totally refuted this previous work: he had come to understand language as a sort of word game where one had to understand their definitions in the context of their use at the time.

In wine speak; it certainly does help if you have some idea of the rules of the game.

When assessing the characteristics of a wine we look at its colour, its aroma, its flavour and other in-mouth sensations such as texture and structure; these characteristics are described as primary: characters derived from the grapes from which the wine is made, secondary: derived from characters imparted during the winemaking process, and in older wines tertiary: characteristics that develop in the wine as it ages.

Given the absence of unique and specific language to describe specific aroma and flavour we are often left to use comparisons or similarities as descriptors for the aromas and flavours in wine (smells like this, tastes like that). This is perfectly acceptable because many of the aroma compounds found in ripening grapes are similar to those found in other fruits, vegetables and plants. Many of the descriptors used to describe secondary characters in the wine are merely descriptors of a material or process used to make the wine (oak barrels, yeasts, etc.), whilst other terms describe texture and structure (creamy, smooth, tannic, etc).

However, once you start making similarities to describe characters in wine and unlocking the connection between smell and language from smell memory, almost anything can and often is tossed up as a descriptor for wine. It appears that some wine writers even play on this as a sort of false air of their own sophistication and ability.

To try and derail this potential tower of Babel, UC Davis University in California developed its own version of the Rosetta Stone, the ‘Wine Aroma Wheel’; a tool used widely throughout the world by industry professionals to help develop a universal language for the description of wines. It is a very useful tool that takes commonly made similarities in wine back to their origin or source, be that primary, secondary or tertiary.

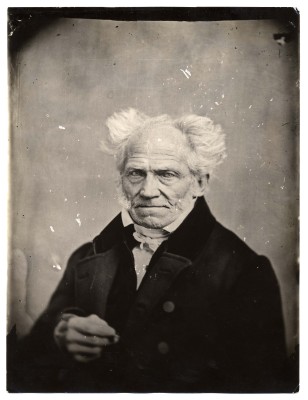

Get on the net and have look at the Wine Aroma Wheel and use it to try and decipher the tasting notes on the back label of the next bottle of wine you purchase -then see if you agree. If you still can’t make head or tail of it don’t be concerned, for I will refer you to another of my favourite philosophers, Arthur ‘Ugly Arty’ Schopenhauer, who famously deduced that everything in the universe was actually a single entity, a ‘great oneness’, it was merely humans beings in their observations that made any differentiation at all.

But is it Art?

We tend to experience feelings of guilt when it comes to food and the things we ingest; as a society we tend to frown upon overindulgence and are preoccupied with body image. In a world where people are starving it is perhaps not right to glorify food as something more than sustenance. In a world where food security is an increasingly urgent matter the evolution of cuisine should be focused on how to make it more sustainable and healthier not molecularly altered and gastronomically avant garde.

Yet, despite all of this confounded opinion, to me there is undeniable beauty in food and wine and all it encompasses and may represent on the plate and in the glass. Taking products of this earth, the soil, the sea, to subject them to the manipulations of Mother Nature, to her temperamental weather and then have someone with great passion use their imagination and creativity to produce something magical and bring the two of these creations together, the food and the wine, is a thing of great wonder. It is as interpretive as taking pigments from the soil and translating them into an oil painting or cleaving instruments from things of stone and wood and composing a musical number. The fact that we ingest this work, take it inside of our bodies as well as our minds and allow our bodies to extract from it what it will, all the goodness and discard what it does not need, whilst we process this creation on several levels in our brains, because chemically it has the power to alter our mood and the way we feel as well as aesthetically having the power to stimulate us intellectually and this is unique.

No, I don’t think that food is art and I do think that food is important, how we produce it is important and how we distribute it is important. I do also feel that great chefs can take food and create something that transcends mere preparation, mere cooking; they can create art and it can be appreciated with the senses in a deeply profound way. This is something that can and should be enjoyed, it doesn’t have to be wasteful, decadent or pretentious, it can just be good and it can be appreciated in that way. We can appreciate cuisine in an artistic way for the flavour sensations and combinations, the complexity, marriage and balance of flavours, textures, intensity and subtleties and we can appreciate it for the feelings, emotions and thoughts it evokes in us, much like a performance piece. Sometimes food can be simple and wholesome and sometimes it can be complex and highly stylized and often it is much, much more than merely sustenance.