Gnadenfrei ‘free by the grace of god’

Marananga ‘by my own two hands’

The Barossa Valley is one of Australia’s oldest and most celebrated wine regions, enjoying a history as rich and complex as its world-famous wines.

In December 1837, British Naval and Army Officer, Surveyor General of the Colony of South Australia, Colonel William Light led an expedition into the region and two years later it was surveyed by William Jacob. Colonel Light chose the name ‘Barrosa’ in memory of the British victory over Napoleon’s French forces at the Battle of Barrosa in 1811, a battle in which he had fought. The name “Barossa” was registered due to a clerical error in transcribing it and was never changed.

Up until the 1840’s, most of Australia’s wine industry had been influenced by the British however, the agriculture of the Barossa Valley would be shaped by Germanic settlers, Lutherans fleeing persecution by the Prussian King Friedrich Wilhelm III, in their native province of Silesia, (now part of Poland).

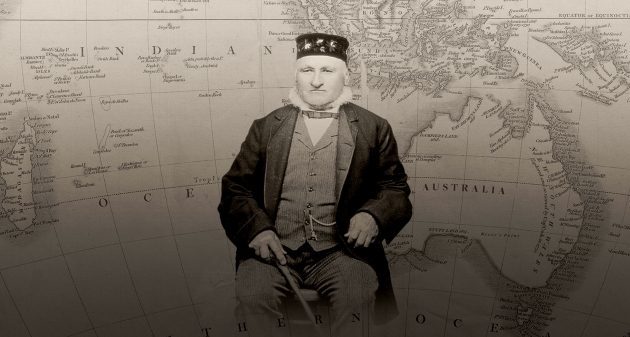

In 1841, ‘The South Australian Company’, (under the direct orders of its Chairman and major shareholder, George Fife Angas) chartered three ships to Silesia with an offer of refuge and land to any settler willing to help establish the colony. Nearly 500 families took up the invitation and resettled in the Barossa Valley.

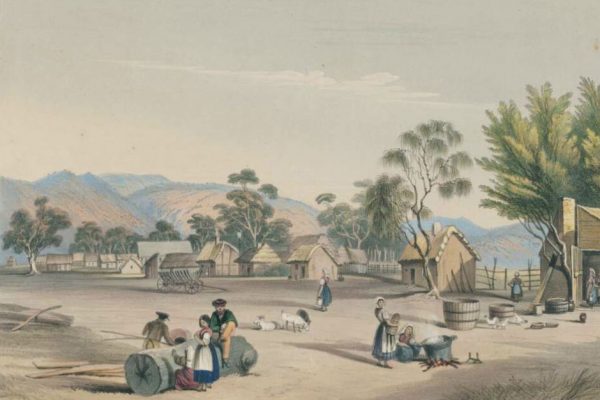

The first German families settled around Bethany in 1842, further settlements were soon established in Angaston, Krondorf, Ebenezer, Penrice, Light Pass and Langmeil, followed by Tanunda, Gnadenfrei, Hofffnungthal, New Mecklenburg, Siegerdorf, Neukirch, Nuriootpa, and Seppeltsfield. It was not long before it was recorded that Lutheran Church spires could be seen all over the valley. An Adelaide newspaper reported in 1843 that the Germans made a highly valuable class of colonists, they were an exceedingly industrious, sober and persevering people whose progress in the colony had been most creditable.

The German traditions have been preserved in the Barossa Valley, especially in and around the township of Tanunda where the Liedertafel, (a 45-member all-male, German choir whose origins date back to the 1850’s) still performs. There is even a local dialect known as Barossa German; when Daniel Brock began collecting statistics for the South Australian Almanac, (sometime around 1843) he noted that the only person in the township of Bethany who spoke any English at all was the schoolmaster.

Gold was discovered in the Barossa Valley area some twenty years later, (1860’s) and South Australia’s largest gold rush ensued, quickly bringing thousands of prospectors into the area. In 1862, a large copper deposit had been found at nearby Kapunda and the influence of Cornish miners can still be seen today, especially in the township of Angaston. This saw demand for produce in the area thrive and helped the y0oung region prosper.

Nepenthe for the Soul

“Whether wine is a nourishing drink, a medicine or a poison is a matter of dosage.”

Paracelsus, 1493-1541, alchemist, astrologer, physician;

Father of modern pharmacology and toxicology

Wine and medicine have been inextricably linked since the days of antiquity, its medicinal uses have been recorded by the Ancient Egyptians, Greeks and Romans.

The Hippocratic Oath is historically taken by physicians and it remains the most widely known of all Greek medical texts. It requires Physicians to uphold specific ethical standards and is the earliest example of medical ethics in the western world. This oath remains as a rite of passage for medical graduates in many countries around the world, to this day.

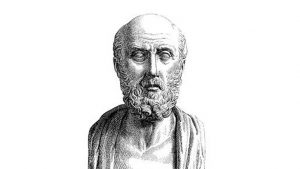

Hippocrates of Kos (460 BCE – 370BCE) was a Greek Physician in the age of Pericles, he is considered by many as the ‘Father of Medicine’, in recognition of his lasting contributions to the field as the founder of the Hippocratic School of Medicine.

Hippocrates described symptoms of scurvy in his books, Prorrheticorum and Liber de internis affectionibus and the knowledge that consuming foods rich in vitamin C is a cure would be repeatedly forgotten and then rediscovered for several hundred years.

During the ‘Age of Exploration’, when the great sailing ships of Europe began exploring the planet (approximately 1500 to 1800) it has been estimated that over two million sailors lost their lives to this very preventable condition. In his book ‘Preserving the Self in the South Seas, 1680-1840’, Jonathan Lamb wrote: “In 1499, Vasco da Gama lost 116 of his crew of 170; In 1520, Magellan lost 208 out of 230; all mainly to scurvy.”

Most species produce their own vitamin C, (ascorbic acid) and it is within our human DNA to produce it as well however, due to a mutation in the GULO, (gluconolactone oxidase) gene we have an inability to synthesize the protein. Normal GULO is an enzyme that catalyzes the reaction of D-glucuronolactone with oxygen to L-xylo-hex-3-gulonolactone. This then spontaneously forms Ascorbic Acid (Vitamin C). However, without the GULO enzyme no vitamin C is produced. Aside from humans, only guinea pigs, bats and dry-nosed primates have lost their ability to produce vitamin C in the same way.

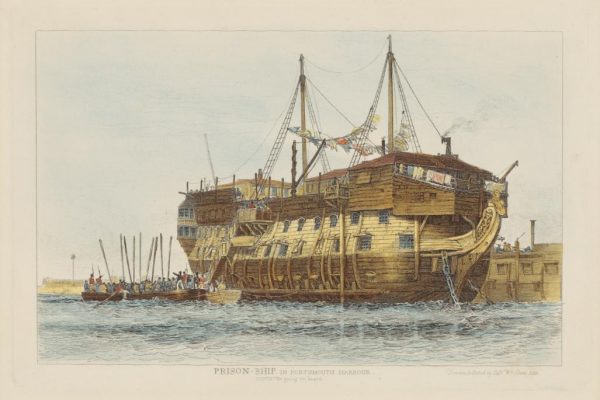

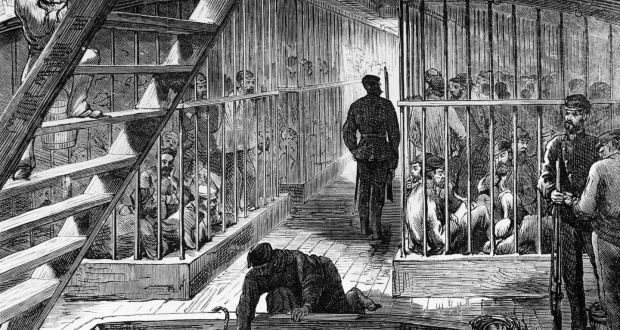

According to Australian Government statistics, some 162,000 convicts were transported by the British government to various penal colonies in Australia between the years 1788 and 1868. This was undertaken in order to deal with the problem of over-crowding in British Jails, disease running through the jails and then breaking out into general population and a desire to rid themselves of what was perceived as a ‘criminal’ class, unfit for British society. The government began transporting convicts across the planet to the colonies in America in the early 18th century.

With the onset of the American Revolution, transportation ended and an alternative site quickly needed to be found, such was the overcrowding of British prisons, that hulks full of prisoners now sat in rivers and ports right across Great Britain. Australia was soon chosen as the site of a new penal colony and on the 13th of May, 1787, the First Fleet of eleven convict ships set sail from Portsmouth England, through the Spithead bound for Botany Bay, arriving on 20th January 1788.

Other penal colonies were later established in Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania) in 1803 and Queensland in 1824, while Western Australia, founded in 1829 as a free colony, received convicts from 1850.

Victoria and South Australia remained free colonies. Penal transportation to Australia peaked in the 1830s and dropped off significantly the following decade. The last convict ship arrived in Western Australia on 10 January 1868.

Cramped and unsanitary quarters, poor hygiene, poor rations and a poor diet along with a lack of sufficient medicines and medical treatment were common on the earliest fleets and mortality rates high. Average mortality rates where at 5 to 10 percent of passengers whilst the notorious second fleet had a mortality rate of 40 percent of its passengers. On the early convict ships to Australia scurvy, (from lack of vitamin C) was a major cause of death.

The Breeze at Spithead

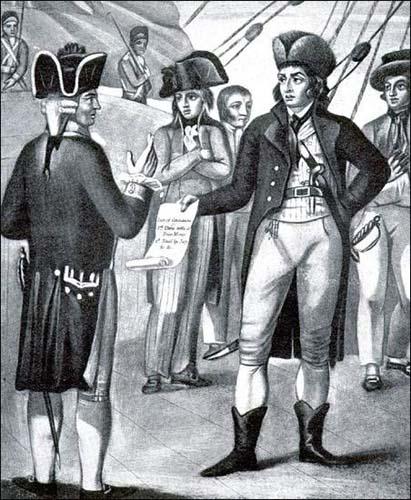

The anchorage at the head of The Solent, between Portsmouth and Ryde, on the Isle of Wight, is known as Spithead; on the 16th of April, 1797, (just eight years and eleven months after the first fleet sailed from the same anchorage to settle Australia) sailors on 16 ships of the first fleet, (commanded by Admiral Lord Bridport) took control of their ships, essentially a protest, it was called a mutiny.

The Mutiny would last a month, with the seaman demanding better living conditions aboard Royal Navy vessels a pay rise, better victualling, increased shore leave, and compensation for sickness and injury. On 26th of April, a supportive mutiny broke out on 15 ships in Plymouth, who sent delegates to Spithead to take part in the negotiations.

According to the Council of Delegates at Spithead “From the Delegates to the Admiralty” in The Naval Mutinies of 1797 ed. Conrad Gill (Manchester University Press, 1913), seamen’s pay rates had been established in 1658, and because of the stability of wages and prices, they were still reasonable as recently as the 1756–1763 Seven Years’ War. However, high inflation during the last decades of the 18th century had thus severely eroded the real value of the pay and in recent years pay raises had been granted to the army, militia, and naval officers.

At the same time, the practice of coppering the submerged part of hulls, which had started in 1761, meant that British warships no longer had to return to port frequently to have their hulls scraped, and the additional time at sea significantly altered the rhythm and difficulty of seamen’s work. The Royal Navy had not made adjustments for any of these changes, and was slow to understand their effects on its crews. Finally, the new wartime quota system meant that crews had many landsmen from inshore who did not mix well with career seamen, leading to discontented ships’ companies.

Earl Spencer in “Spencer’s Diary, 18 April 1797” in The Naval Mutinies of 1797 ed. Conrad Gill (Manchester University Press, 1913) records that the mutineers were led by elected delegates and tried to negotiate with the Admiralty for two weeks, focusing their demands on better pay, the abolition of the 14-ounce “purser’s pound” (the ship’s purser was allowed to keep two ounces of every true pound—16 ounces—of meat as a perquisite), and the removal of a handful of unpopular officers; neither flogging nor impressment were mentioned in the mutineers’ demands.

The mutineers maintained regular naval routine and discipline aboard their ships (mostly with their regular officers), allowed some ships to leave for convoy escort duty or patrols, and promised to suspend the mutiny and go to sea immediately if French ships were spotted heading for English shores.

Because of mistrust, especially over pardons for the mutineers, the negotiations broke down and minor incidents broke out, with several unpopular officers sent to shore and others treated with signs of deliberate disrespect.

When the situation calmed, Admiral Lord Howe intervened to negotiate an agreement that saw a royal pardon for all crews, reassignment of some of the unpopular officers, a pay raise and abolition of the purser’s pound. Afterwards, the mutiny was to become nicknamed the “breeze at Spithead”.

The Nore

Inspired by the example of their comrades at Spithead, the sailors at the Nore in the Thames Estuary also mutinied, on 12 May 1797, when the crew of the Sandwich seized control of their ship.

One of the ships taken over by its crew was HMS Director, captained by William Bligh who had already survived the ‘Mutiny on the Bounty’ in 1789 and returned to active service. Whilst HMS Director’s role was said to be relatively minor in this mutiny, she was the last vessel to raise the white flag when it came to its end.

Demands were formulated and on 20 May 1797 and a list was presented to Admiral Charles Buckner, which included demands for pardons, increased pay, a modification of the Articles of War and demands were later expanded to include that the King dissolve Parliament and make immediate peace with France, which came as the mutineers began to blockade merchant ships in and out of London. This infuriated the Admiralty and so Captain Sir Erasmus Gower commissioned HMS Neptune (98 guns) in the upper Thames and put together a flotilla of fifty loyal ships to prevent the mutineers moving on to the city of London.

After the resolution of the Spithead mutiny, the government and the Admiralty were not minded to make further concessions, particularly as they distrusted the motives of some leaders of the Nore mutiny, who had political aims beyond improving pay and living conditions. The mutineers were denied food and water and the mutiny soon began to fall apart; in the reprisals which followed, 29 mutineers were hanged, 29 were imprisoned, and nine were flogged, while others still were sentenced to be transported to Australia.

One of those sentenced to death was a twenty-two-year-old, surgeon’s mate serving on the H.M.S. Standard, his name was William Redfern. When the Mutineers evicted the ship’s surgeon young Redfern -just five months into his navel career- took his place and later convicted on the evidence of a letter he had penned that was said to show sympathy for the rebel’s cause.

Fortunately for the young Doctor, his sentence was commuted to life imprisonment and after languishing in a prison hulk for several years he was eventually transported to New South Wales in Australia. Redfern set forth on the HMS Canada convict ship which sailed in company with the Minorca and the Nile on the 6th of June 1801. At some point during the journey, Redfern was transferred to the Minorca where he assisted the surgeon before arriving in Sydney on the 14th of December 1801.

Medical men in the young colony were obviously in short supply and within a year Redfern was granted a conditional pardon and sent to Norfolk Island by the Governor of New South Wales, Philip Gidley King, who had recently been charged with colonizing the island. King assigned Redfern to the post of assistant surgeon and the following year granted him a full pardon. Redfern obviously enjoyed the role and remained on Norfolk Island from 1802 until he returned to Sydney in 1808.

Lieutenant-Colonel Joseph Foveaux was in charge of Norfolk Island at the time of Redfern’s appointment and it has been recorded that the surgeon performed his duties admirably, winning great respect amongst those on the island. Redfern must have formed a strong bond of friendship with the Lieutenant-Colonel, having married to Sarah Wills, Redfern named their second son, (born 1830) Joseph Foveuax Redfern.

Rum Mutiny

As previously mentioned, Vice-Admiral William Bligh is well known as an officer of the Royal Navy, for the infamous ‘Mutiny on the Bounty’ which occurred during his command of the H.M.S. Bounty in 1789.

After being set adrift in the Bounty’s launch by the mutineers, Bligh and those men who remained loyal to him somehow managed to sail 3,618 nautical miles (6,701 km) to Timor.

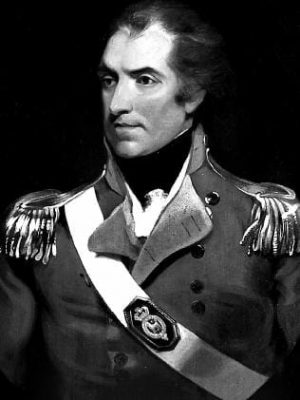

Just seventeen years after the Bounty mutiny, on 13 August 1806, Bligh was appointed Governor of New South Wales, Australia. He had repaired his reputation to some degree after garnering the praises of Lord Nelson during for his efforts during the Battle of Camperdown. Bligh was now given strict orders to clean up the rampant corruption in the trading of rum, especially amongst the New South Wales Corps.

It has been noted that he was in all likelihood selected by the British Government because of his reputation as a hard man; they had believed he stood a good chance of reining in the maverick New South Wales Corps, something that his predecessors had not been able to do.

Even before his arrival there was trouble on the voyage, Bligh after a run in with the commander of another vessel on the journey had him stripped of the captaincy of the vessel, awarding it to his own son-in-law who had accompanied him on the journey.

During his time as governor Bligh largely ceased the practice of handing out large land grants to those with wealth and power in the colony; during his tenure he granted just over 1,600 hectares of land but half of that was to his daughter and to himself.

Bligh, in trying to smash the rum monopoly and severely reign in the power of the newly wealthy, free and freed settlers, had made powerful enemies. He dismissed D’Arcy Wentworth from his position of Assistant Surgeon to the Colony without explanation, and sentenced three merchants to a month’s imprisonment and a fine for writing a letter that he considered offensive. Bligh also dismissed Thomas Jamison from the magistracy, describing him in 1807 as being “inimical” to good government. In October 1807 Major George Johnston wrote a formal letter of complaint to the Commander-in-Chief of the British Army, stating that Bligh was abusive and interfering with the troops of the New South Wales Corps.

However, the fatal blow to his career as Governor of the new colony was to make an enemy of and then attempt to arrest John Macarthur, retired British Officer, one of the most powerful and probably the wealthiest man in the entire country.

These actions resulted in the what has been dubbed the ‘Rum Rebellion’, when at 6:00 pm on the 26th of January, (Australia Day) 1808, soldiers of the New South Wales Corps under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel George Johnston, with full band playing and colours proudly flying, marched on Government House to arrest Bligh. According to journalist and historian Michael Duffy, the troops met no resistance save for a swinging parasol of one Mrs. Mary Putland, Bligh’s daughter.

They found Bligh in full-dress-uniform hiding behind his bed and whilst he always claimed to be hiding papers and there is some support by historians for this, he would be branded a coward. Shortly after Bligh’s arrest, a watercolour by an unknown artist was exhibited in Sydney; the illustration depicts a soldier dragging Bligh from underneath one of the servants’ beds with two other figures standing by.

The two soldiers in the watercolour are most likely John Sutherland and Michael Marlborough and the other figure on the far right is said to represent Lieutenant William Minchin. This painting is Australia’s earliest surviving political cartoon and like all political cartoons it made use of caricature and exaggeration to convey its message.

As described by author Richard Neville in his work ‘Australiana’, the New South Wales Corps officers regarded themselves as gentlemen and in depicting Bligh as a coward, the cartoon declares that Bligh was not a gentleman and therefore not fit to govern.

The origins of the watercolor professed to have stemmed from a dispute between Bligh and Sergeant Major Whittle, commenced when Bligh demanded Whittle pull down his house as it was halting improvements to the town. It has been suggested Whittle saw his opportunity and quickly commissioned the painting.

Bligh would be held under house arrest and eventually ordered to return to England, even though the British Foreign Office, (eventually) declared it to be an illegal mutiny.

Charles Grimes, the Surveyor-General, as Judge-Advocate ordered Macarthur and the six officers be tried; they were found not guilty. Macarthur was then appointed as Colonial Secretary and effectively ran the business affairs of the colony. Another prominent opponent of Bligh, Macarthur’s ally Thomas Jamison, was made the colony’s Naval Officer (the equivalent of Collector of Customs and Excise). Jamison was also reinstated as a magistrate.

Joseph Foveaux (1767 – 1846) joined the New South Wales Corps in June 1789 as a lieutenant and reached Sydney in 1791. He was soon promoted to the rank of major and then as senior officer and from August 1796 until November 1799, he was effectively in control of the Corps, this was at a time senior officers were making fortunes from trading and extending their lands. Foveaux soon became one of the largest landholders and stock-owners in the new colony.

In 1800, Foveaux offered to go to Norfolk Island as Lieutenant-Governor. He built up the run-down island and earned the praises of Governor King. Foveaux left Norfolk Island in 1804, returning to England for a time before setting off again for New South Wales to serve as Lieutenant-Governor.

On his arrival in July 1808, Foveaux found Governor Bligh under arrest by his fellow officers of the New South Wales Corps and it was Foveaux who assumed control of the colony.

Dr. William Redfern, who had worked with Foveaux on Norfolk Island and become his great friend, the same Redfern who had once before been sympathetic to the plight of mutineers at The Nore, where a ship under Bligh’s command was involved- was summonsed to return to Sydney and take up the position of assistant surgeon.

In January 1809, the acting Lieutenant-Governor, Colonel William Paterson, returned and Foveaux remained to assist him and his successor, Major-General Lachlan Macquarie.

William Redfern, as a convict had no documentary evidence of his qualifications and this needed to be overcome so he was required to pass a new examination by the colony’s prominent surgeons: Principal Surgeon Thomas Jamison; Surgeon of the New South Wales Corps, John Harris and assistant Surgeon to the Corps, William Bohan. Passing the exam, (apparently with flying colours) made Redfern the first person to receive Australian qualifications as a medical practitioner and this enabled Governor Lachlan Macquarie to ratify his appointment.

Of Redfern, Governor Macquarie is quoted as saying, “He is one of the best educated men that I’ve come across,’’ and Redfern’s first-born son was named William Lachlan Macquarie Redfern.

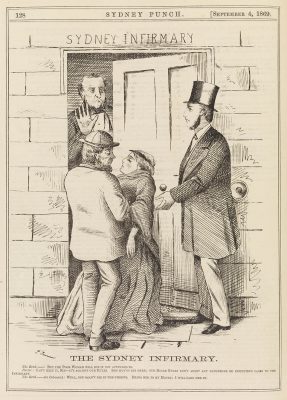

The Rum Hospital

A great many of the convicts who survived the voyage on the First Fleet in 1788 arrived suffering from dysentery, smallpox, scurvy, lice and typhoid. Soon after landing Governor Phillip and Surgeon-General John White established a tent hospital along what is now George Street in The Rocks to care for the worst cases. Subsequent convict boatloads had even higher rates of death and disease.

A portable hospital which was prefabricated in England from wood and copper arrived with the Second Fleet two years later. Nurses Walk in ‘The Rocks’ in Sydney, cuts across where the site of the early hospital once stood.

Upon arriving in the Colony at the beginning of 1810 and discovering that Sydney Cove’s hospital was a ragged assembly of tents and temporary buildings, Governor Macquarie set aside land on the western edge of the Government Domain for a new hospital. He also created a new road, called Macquarie Street to provide access to it.

Plans were drawn up but the British Government refused to provide the necessary funds to build the hospital. Consequently, Macquarie entered into a contract with a consortium of businessmen; Garnham Blaxcell, Alexander Riley and D’Arcy Wentworth, (Wentworth played a significant role in the Rum Rebellion against Governor William Bligh and participants in the rebellion claimed that Bligh had suspended Wentworth from his role as assistant surgeon on the staff, without reason or justice). The consortium would provide the funds in exchange for a monopoly on the importation of rum and the provision of convict labour, in order to gain profit from their investment. They had permission to import rum, the generic term for all liquors, to a total of 45,000 (204,574 litres) which was then increased to 65,000 gallons (295,496 litres). The ‘contract’ was signed on the 6th November 1810 and Convict patients were being transferred to the new hospital by 1816.

The early hospital quickly and regretfully gained a reputation as the “Sydney’ Slaughterhouse” as it was said people who went in rarely came out alive. Francis Greenway, the Colonial Architect, inspected the hospital buildings and declared its construction and materials to be sub-standard, noting it had weak foundations and that short cuts that had been taken in its construction. For their worth, the three investors claimed the whole enterprise was unprofitable, but one wonders given they would have had no problem selling the vast amounts of rum they were allowed to import.

The Age of Discovery

In an era of great nautical exploration, known as the ‘Age of Discovery’, (early 1500’s to late 1800’s) the British Empire had its fair share of heroes on the sea; names like Sir Francis Drake and Captain Cook are still relatively well known today. However, none were as renowned and admired as that of Lord Nelson, a name synonymous with great victory and great bravery on the high seas. He was regarded, not only as one of Britain’s finest seamen, but as one of its great military leaders. As recently as the 2002, Nelson was voted the 8th Greatest Briton of all time in a BCC program titled the ‘100 Greatest Britons’; placing him just slightly behind Elizabeth I and ahead of Sir Isaac Newton and William Shakespeare.

Trafalgar Square in the heart of London is a monument and public space named for his greatest victory, off the coast of Cape Trafalgar, in its center stands ‘Nelson’s Column’ a Corinthian column of granite that stands 51.5-meters tall with four large bronze lions at its base and a 5.5-meter sandstone statue of Lord Nelson atop the column, proudly and defiantly looking out to sea.

Vice Admiral Horatio Nelson, 1st Viscount Nelson, 1st Duke of Bronté, KB (1758 – 1805) was a British flag officer in the Royal Navy. He was noted for his inspirational leadership, grasp of strategy, and unconventional tactics, which resulted in a number of decisive and historically famous British naval victories, particularly during the Napoleonic Wars, including what is generally considered its greatest ever naval victory, the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805.

Sailing at this time was a deadly affair and Nelson was wounded several times in combat, losing the sight in one eye in Corsica and most of one arm in the unsuccessful attempt to conquer Santa Cruz de Tenerife. He was shot and killed during his final victory at the Battle of Trafalgar near the port city of Cádiz in 1805.

Nelson’s body was placed in a cask of brandy mixed with camphor and myrrh, which was then lashed to the Victory’s mainmast and placed under guard. Victory was towed to Gibraltar after the battle, and on arrival the body was transferred to a lead-lined coffin filled with spirits of wine so it could be returned to London.

Vice Admiral Cuthbert Collingwood’s dispatches about the battle were carried to England aboard the somewhat ironically named HMS Pickle.

It was reported in ‘The Times’ that despite the magnitude of the victory of Trafalgar, King George III, on receiving the news of Nelson demise said, with tears in his eyes, “We have lost more than we have gained.” The Times went on, “We do not know whether we should mourn or rejoice. The country has gained the most splendid and decisive Victory that has ever graced the naval annals of England; but it has been dearly purchased.”

Tapping the Admiral

In the Royal Navy the term tapping the admiral became a common term to describe the practice of sneaking liquor by sucking it directly from a cask through a straw. This involved making a small hole with a gimlet into a keg or barrel and using a straw to suck out the contents.

The story goes that the cask used to ‘preserve’ Lord Nelson was opened at Gibraltar only to discover that it had been emptied of its alcoholic contents. The pickled body was removed and it was soon discovered that the sailors had drilled a small hole near the bottom of the cask and sucked out its liquid contents. Thus, this tale serves as a basis for the term being used to describe surreptitiously sucking liquor from a cask through a straw.

Surgeon William Beatty also recorded that on October 28, 1805 during the voyage gases from the corpse caused the cask lid to burst open on, which was somewhat alarming to the guard on duty at the time.

The Standard

The HMS Standard, the very ship that William Redfern had been on at The Nore during the infamous mutiny, was a 64-gun Royal Navy third-rate ship of the line.

It had been recommissioned in August 1805, under Captain Thomas Harvey and sailed to join Rear-Admiral Sir Thomas Louis’s squadron which was attached to Cuthbert Collingwood’s Mediterranean fleet, the same fleet that fought alongside Nelson at Trafalgar. The HMS Standard it seems managed to avoid the battle, when Louis’s squadron was dispatched to Gibraltar to collect supplies just before the fighting commenced.

Redfern’s Vineyard

Surgeon William Redfern was appointed to the Rum Hospital to provide medical care for the convict patients, and he moved in to his quarters in the south wing (now The Mint) in 1816.

By now, Redfern was the colony’s leading expert in the prevention of disease on board convict ships, having been appointed two years before to investigate the huge losses of life on board the convict transport ships Surry, General Hewitt and Three Bees. Redfern proposed fundamental changes to ventilation, cleanliness, fumigation, diet and clothing, provision of sufficient water, a generous allowance of wine, giving convicts time on deck to get fresh air and sun and the employment of competent surgeons with independent authority over the convicts on board. With these measures in place there were far fewer convict deaths on subsequent voyages and Redfern’s report is considered the greatest administrative development in the history of convict transportation.

After Redfern’s regulations were put into effect death rates for convicts at sea quickly fell from 11.3 per 1000 to 2.4 and in the 1850s to one per 1000. Thus wine has always been associated with good health since the very beginnings of European settlement in Australia and for many years wine and wine distillate were brand and marketed as health tonics.

Admiral Arthur Phillip (1738 – 1814) was the first Governor of New South Wales, he founded the British penal colony in 1788 that later became Sydney, Australia. Phillip retired in 1805, the same year that Nelson met his demise, having already established the colony and the planting of Australia’s first official vineyard at Farm Cove. It was considered vitally important to establish vines and begin making wine in the new colony, as wine was seen as something of a panacea, a nepenthe essential to one’s good health.

Fascinatingly enough, in 1787, Captain William Bligh took command of the Bounty and in order to win a premium offered by the Royal Society, he first sailed to Tahiti to obtain breadfruit trees, then set course east across the South Pacific for South America and the Cape Horn and eventually to the Caribbean Sea, where breadfruit was wanted for experiments to see whether it would be a successful food crop for African slaves, working there on British colonial plantations in the West Indies islands.

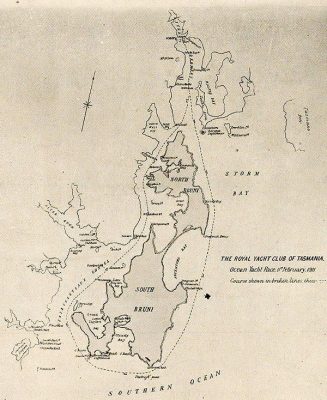

On the first breadfruit voyage, in 1788, the Bounty stopped in at Adventure Bay (Bruny Island, Tasmania) to take on fresh water and rest the crew. Bligh had been here before, when he served under Captain James Cook, during Cook’s third and final great voyage. Bligh served as the ships master under Cook’s command and guidance. Cook arrived in Adventure Bay on January 26th 1777 and recorded a site he said would be ideal for an orchard. Eleven years later, (1788) with Bligh as captain of the Bounty, saw him come prepared, bringing along vine cuttings, small fruit trees and a range of vegetable seeds, which he had obtained at the Cape of Good Hope in Africa, specifically to plant at here at Adventure Bay.

Bligh and his crew cleared land and planted several dozen apple trees, many rows of vegetable seeds and 9 grape vines. They stayed on Bruny Island for a several weeks, exploring and making sure plantings were established, then set off for Tahiti and the inevitable mutiny that was to follow.

Bligh of course, survived the mutiny that later followed on that fateful journey and managed to continue on with his naval career; he returned to Adventure Bay just four years later in 1792. On this return trip, (the second breadfruit voyage) he stopped in at Bruny Island to check his little vineyard and orchard, only to find that everything had been burned and only one apple tree was left alive, ‘quite stunted but with a few apples of bright green skin and a sharp, tangy, crisp taste’.

Captain Phillips plantings at Farm Cove also failed, it was decided the vines were too close to the sea and new sites further inland were selected for further planting of vineyards, orchards and fields.

Dr. William Redfern planted his vineyard in 1818 at his property near Campbelltown in Sydney. Around the same time, Sir John Jamison, past surgeon to the King of Sweden’s fleet planted a vineyard at Penrith, on a property he’d named ‘Regentville’, after his close friend the Prince Regent, later King George the 4th.

Redfern was an extremely successful ex-convict, he was appointed a magistrate by Macquarie and was one of the first directors of the Bank of New South Wales, when he passed, he left extensive land holdings and well-regarded properties. One of those properties today bears his name as a suburb of Sydney.

Today in suburb of Sydney that is named after Dr. William Redfern, vines and wines have returned to the urban enclave, with the opening of Cake Winery’s Cellar Door at 16 Eveleigh Street, although the wines are sourced primarily from the Adelaide Hills, founder Glen Cassidy set up their tasting room, restaurant come entertainment venue here and today it is one of the Redfern communities most popular attractions and a cultural epicenter for the place.

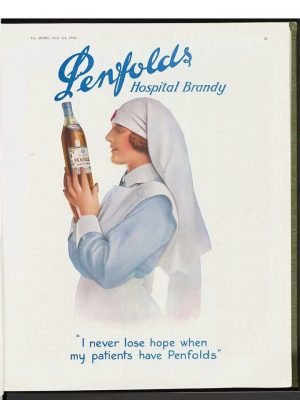

Other wine-doctors soon followed Redfern, many establishing vineyards to make wine for their patients. More than 160 wine-doctors including the founders of some of Australia’s largest and best-known wine established vineyards with great success. Many of Australia’s finest and most famous wine companies were actually founded by doctors, wineries such as Penfolds, Lindemans, Hardys, Angoves, Houghtons, Minchinbury and Stanley. Dr. Penfolds winery and that of Dr. Hardy would go on to play important roles in the development of the Barossa Valley.

Barossa Beginnings

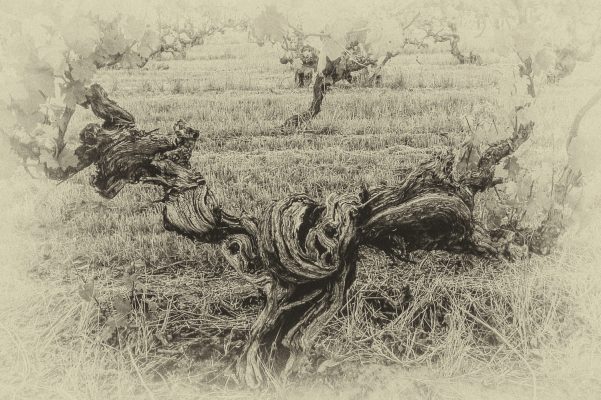

Today in the Barossa Valley, South Australia, there are grape growers that are the sixth generation of their families to do so; custodians to Australia’s largest collection of old vines. Some of these vines date back as far as the 1840’s -just 20 odd years after Redfern planted his vineyard in Sydney- and they are still producing some of Australia’s finest and most famous wines.

Johann Gramp is credited with planting the first vineyard in the Barossa Valley at the then recently named Jacob’s Creek in 1847. Within three years he produced his first wine, a ‘Hock’ style white produced in a single, octave barrel, (about 12 dozen bottles) the wine would later become known by the name Carte Blanche.

Gramp was born on the 28th August 1819 in Eichigt near Kulmbach in Bavaria, in 1837, he left Hamburg to migrate to Australia on the ‘Solway’ via Rio de Janeiro and the Cape of Good Hope. He arrived at Kangaroo Island on 16 October 1837.

He remained on Kangaroo Island for two years working for the South Australia Company, before being transferred to Port Adelaide. For a time, he then worked in a bakery in Adelaide before, then a farm hand in Yatala, before moving to the Barossa to establish his own farm in 1847, after 1950 he expanded his vineyards and added a cellar to his estate. Johann’s son Gustave built a winery at Rowland Flat in 1877, naming it Orlando which has its origins in the Italian language, (it is said to be the Italian version of the name Rowland) and is meant to mean “famous throughout the land”, it is also the name of a character in Shakespeare’s play ‘As You Like it’ (1599).

The estate at Jacob’s Creek would remain in the hands of the Gramp family until 1972, when it was purchased by Reckitt and Colman who in turn sold it to the giant French beverage producer Pernod Ricard in 1989. The Jacob’s Creek wine label is still one of the world’s most famous wine brands and Orlando one of Australia’s leading wine producers.

Joseph Ernest Seppelt was a merchant in Silesia who sold such commodities as tobacco, snuff and liqueurs, he emigrated with his family from Prussia in 1849, to break free of the political and economic unrest, like so many other Silesians of the time.

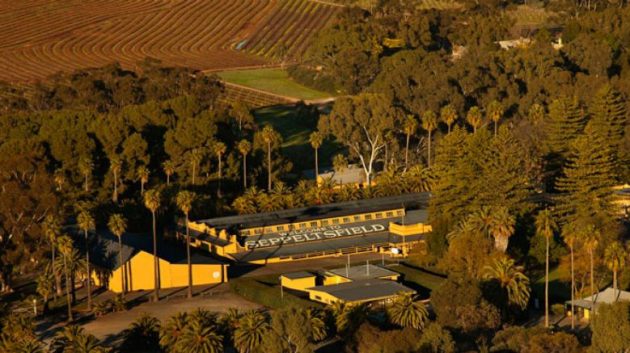

Seppelt arrived with his wife Charlotte, his two sons, Benno and Hugo, daughter Ottilie, thirteen families and a group of young men who had worked for him. He settled at Klemzig with the ambition of growing tobacco however soon found the land unsuitable and instead moved on to the Barossa Valley. In 1851, Seppelt purchased 64 ha of land for £1 an acre and named it Seppeltsfield.

He soon discovered that, as was the case in Klemzig, the land and climate in the Barossa Valley was not suitable for growing tobacco. The Seppelts did however enjoy some success with growing wheat on their land and, due to the gold rushes of the 1850s, were able to sell at high prices.

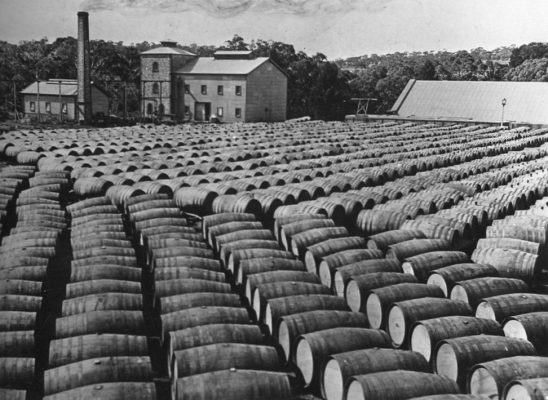

Seppelt also planted vines that flourished, so that by 1866 he was contributing Wines and Spirits to the Melbourne Intercolonial Exhibition. A year later construction had begun on a large winery, in 1878 Joseph passed away but the winery continued to expand and improve under the stewardship of his son Benno Seppelt. By the turn of the century, the Seppelt Winery was Australia’s largest winery, producing 2 million litres annually.

Winemaking in the Barossa Valley was not solely a German affair and in 1847 a young brewer named Samuel Smith arrived with his family from Dorset, England aboard the ‘China’. After spending some time settled near the banks of the Torrens River in Adelaide, he packed up the family and set off to take up land at Angaston. By 1849 he and his son Sidney had planted their first vines on the property they have chosen to name Yalumba, an indigenous term that was said to mean ‘all the land around’.

When the gold rush hit Victoria in the 1850’s Samuel, like so many others, could not resist the urge to seek a quick fortune, many a man would return luckless and broke by the harsh realities of life in the goldfield however, Samuel Smith returned after four months with 300 pound in Gold!

This lucky strike would enable him to purchase a further 80 acres of land, to horses and a harness and Yalumba winery was soon one of the major wine producers in the region.

The early years of Barossa Valley winemaking where a long period of trial and error for whilst the Prussian skilled at farming, their homeland of Silesia had little to no winemaking traditions.

The early wines were more often than not made from Riesling, a German wine grape from the Rhineland. The hot valley floor contributed to a very ripe, alcoholic wines, there was no refrigeration and the wines would often quickly turn brown. Wines were soon being distilled into brandy and then came the era of fortified wines, which were more stable and could be transported over long distances without spoiling. This then led to the planting if later ripening thick skinned red varieties like Shiraz, Grenache and Mourvedre, (Mataro) to produce ‘Port’ style fortified red wines that would remain popular for many decades.

Other notable names amongst the region’s first vignerons are the Sobels, Salter (Saltram), Johann Henschke’s Henschke Wines, and Tolleys who, along with Seppeltfield, Yalumba and Orlando soon dominate production in the region. Still others concentrated on growing the grapes to supply these successful wineries. One of the ‘city papers’ reported in 1859 that, ‘The cultivation of wine grapes is carried out to such an extent that there is scarcely a settler who has not a respectable vineyard’. By the turn of the century the Barossa Valley had become the largest wine producer in the colony. Penfolds built their Barossa Valley Cellar door in 1911 and by this time, with their extensive vineyard holdings across the state, they were already producing around one third of all of South Australia’s wine.

War and Words

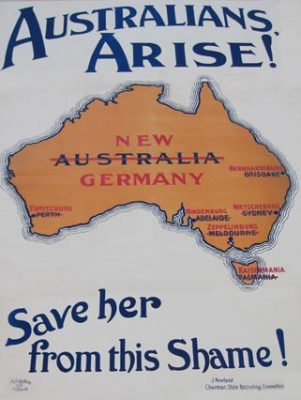

In 1861, towards the end of the Victorian gold rush, people of German origin comprised 4.32% of the total Australian population. They were by far the largest non-British immigrant group. The Chinese, as the second-largest, came to 3.28% by comparison; the Italians as the third-largest made up only 0.21%.

The population of Australia in 1911 was 4,455,005 and by 1914 there were about 100,000 Germans living in Australia. in 1914. Between 1839 and 1914 German-Australians made a major contribution to Australia, particularly in South Australia where by the turn of the century about 10% of the state’s entire population were German migrants or Australians of German descent.

Across the Barossa Valley many of the towns and villages had originally been settled by these German migrants and, (just like their British counterparts) they gave them the names of the towns and places they missed back home or where they had originally come from, names like Hahndorf, Klemzig, Bethanien, Kronsdorf, Langmeil, Lobethal, Jaensch Town, Kaiser Stuhl and many, many more.

On the 28th July 1914, War broke out in Europe between the German led Central forces and the British led Allied forces, it would last until 11th November 2018, it was the largest war in history up until that time and would become known as the world war, or great war before eventually being consigned to history as World War One.

It was through a complex series of alliances amongst the opposing forces that a spat in the Balkans quickly exploded into a conflict that dragged most of the developed world into a maelstrom that would soon settle into a long, bloody, murderous grind.

In the aftermath of the war, four empires disappeared: the German, Austro-Hungarian, Ottoman, and Russian. A numerous number of nations regained their former independence, and a few new ones were created. Four dynasties, together with their ancillary aristocracies, fell as a result of the war: the Romanovs, the Hohenzollerns, the Habsburgs, and the Ottomans. Belgium and Serbia were badly damaged, as was France, Germany and Russia.

Approximately 70 million military personnel were mobilised, including 60 million Europeans. An estimated nine million combatants and seven million civilians died as a direct result of the war, and it directly caused or contributed to later genocides and the 1918 influenza pandemic, which caused upwards of 50 million deaths worldwide.

Germany lost 15.1% of its active male population, Austria-Hungary lost 17.1%, and France lost 10.5%. In Germany, civilian deaths were 474,000 higher than in peacetime, due in large part to food shortages and malnutrition that weakened resistance to disease.

According to Tucker, Spencer in ‘Encyclopedia of World War’: The Australian prime minister, Billy Hughes, wrote to the British prime minister, Lloyd George, “You have assured us that you cannot get better terms. I much regret it, and hope even now that some way may be found of securing agreement for demanding reparation commensurate with the tremendous sacrifices made by the British Empire and her Allies.” Australia received £5,571,720 war reparations, but the direct cost of the war to Australia had been £376,993,052, and, by the mid-1930s, repatriation pensions, war gratuities, interest and sinking fund charges were £831,280,947. Of about 416,000 Australians who served, about 60,000 were killed and another 152,000 were wounded.

When war broke out there was very quickly an air of distrust toward the German communities in Australia; British-Australians felt that many of the Germans in Australia fully supported the Kaiser, (German Emperor). German-Australians were proud of their heritage and culture but politically they were, with few exceptions, loyal to Australia. Most British Australians found it difficult to make this distinction. Many German Australians were in the Australian army and fought and died for Australia. On the war memorial in the public gardens of Tanunda, (Barossa Valley) are the names of eight soldiers who fell in the war. Six of them are German names.

General John Monash was Australia’s most famous commander in the war; having served as commander of 4th Infantry Brigade at Gallipoli, then rising up the ranks until in 1918 he became the commander of the Australian Corps, at the time the largest corps on the Western Front.

Monash was the son of German-Jewish immigrants (the family name was originally Monasch) and he wrote letters to his father Louis in German and had participated in German club life in Melbourne. His parents named their first cottage in 1871 in Richmond “Germania”. Australia’s legendary military tactician was appointed commander of the Australian Army, which was created by the amalgamation of all five Australian divisions in France.

According to Dave Nutting of German – Australian: German Australians described themselves as Australians at a time when others in Australia described themselves as members of the British Empire. In 1914, most white Australians identified with “Mother England.” In her book The Anzacs the Australian author Patsy Adam-Smith wrote:

“The people didn’t know what to do”, my father answered when, as a child, I questioned him about the ill-treatment of a German in his town. “We hadn’t had a war before this.”

Some German Australians were interned, even families who had lived in Australia for up to three generations. Employment became difficult for German-Australians, and as a result some went into internment camps voluntarily. Some British Australians no longer wanted to work together with “Germans” and it became harder for German Australians to find work. Hermann Homburg, the Attorney General of South Australia, had to resign from his position. He was born in South Australia and had never been outside of the State.

German schools were forced to close, and the study of German was forbidden in government schools. The Premier of South Australia said that the Education Department must not employ anyone of German background or who had a German name.

In South Australia all 49 Lutheran schools were closed in 1917 alone. After the winter break many of these were re-opened as state schools in the same buildings, with new teachers. This sudden change was traumatic for the youngest children particularly, as they couldn’t understand why the Government would want to do it.

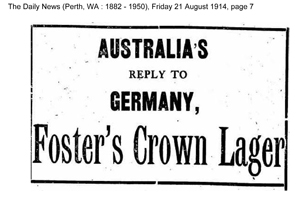

The nationalist fervor of the time helped to increase the sales of Australian lager beer, as fewer imported German beers were sold. The Australian Brewer’s Journal wrote:

“The Teutonic brands which have been imported here by the enemy are taboo. Our lagers are equal if not better than their fancy brands.”

The St Kilda Football Club even went so far as to change its colours in 1915 from red-white-black (the colours of the German imperial flag) to black gold red. It was several seasons before they eventually reverted back to their original colours.

Governments in Australia changed German place names; in South Australia the government changed 69 names of places and geographic features. Bethanien became Bethany, Bismark became Weeroopa, Hahndorf was for a time renamed Ambleside, (till 1935), Kaiser Stuhl became Mount Kitchener until

1975, Klemzig amazingly became Gaza until 1935 and the football club maintained that name.

Langmeil became Bilyara until 1975, Lobethal became Tweedvale until 1935, Rosenthal became Rosedale, Seppelts became Dorrien, Steinfeld became Stonefeld until 1986, Kronsdorf became Kabminye until 1975 and Gnadenfrei became Marananga.

It is interesting to note that Adelaide, the name of the capital of South Australia, was originally German, (Adelheid) although the government in South Australia did not change this place name of German origin. Many German Australians changed their name. Paul Schubert, teacher at Sturt Primary School in Adelaide, had to change his name in order to keep his job. He became Paul Stuart in 1916.

Even the British royal family needed to change its name. Through the marriage of Queen Victoria (1819-1901) to a German prince in 1840 the British royal family had received a German surname. In 1917 King George V. changed the family name. No longer Saxe-Coburg-Gotha; the new family name was Windsor. Victoria’s cousin changed his family name from Battenberg to Mountbatten, as Mountbatten sounded more English.

Just twenty odd years later, Germany and Britain were once again on opposing sides of a war that engulfed the world and Australians of German descent were once again having their loyalty questioned, were distrusted and with many being persecuted.

On September 26, 1999, Governor-General Sir William Deane delivered the opening address at the inaugural Australian Conference on Lutheran Education. In his speech, he offered an apology to members of the German–Australian community present at the meeting:

“The tragic, and often shameful, discrimination against Australians of German origin fostered during the world wars had many consequences. No doubt, some of you carry the emotional scars of injustice during those times as part of your backgrounds or family histories. Let me, as Governor-General say to all who do how profoundly-sorry I am that such things happened in our country.”

There was a brief economic recovery some years after the war; fortified wines had become popular throughout the empire and back in mother England, by 1929 one quarter of all Australian wine production was coming from the Barossa Valley and the rural community was once again thriving.

Then came the Great Depression quickly followed by Word War Two, (60 million lives lost) and all of a sudden export markets had dried up and many Barossa growers were struggling to sell their grapes. Again, there was distrust and a reluctance to do business with German growers and producers

The original Barossa Vintage Festival was planned as a single event – a Thanksgiving Ball in 1947 to celebrate the end of harvest and the end of WWII. It was conceived by Colin Gramp of Orlando Wines and Bill Seppelt of Seppelt Wines and there was no doubt a sense of repairing fractured relationships and putting the past behind them. But the Barossa was struggling, exports markets for fortified wine had all but dried up, along with this challenge, the national palate was also changing and so was the Barossa Valley.

In the late 1940’s and early 1950’s a new Co-Operative movement took over retail outlets and hotels in the area and wineries and winemakers began to modernize their local industry.

Colin Gramp, (a descendant of Johann) spent time in the Napa Valley in the United States, returning in 1947 to make what is believed to be the Barossa Valley’s first dry red table wine since the 1860’s, he would go on to become one of the region’s great innovators.

Penfolds Max Schubert returned from his travels through Bordeaux and was determined to make the great Australian full-bodied red, one with the ability to improve with age over many decades in the cellar. Penfolds Grange of course has gone on to become the Australia’s most famous wine however, it would take over a decade before the wine to even begin to get some recognition in the market.

Higher up in the cooler Barossa Ranges Cyril Henschke produced a single vineyard wine in 1952, naming it Mt Edelstone Shiraz, this was followed by the first Hill of Grace Shiraz in 1958.

In 1956, using cold-stabilization techniques and secondary fermentation, Colin Gramp launched a wine he called Orlando Barossa Pearl. This wine became so successful, especially with young woman, that it opened new markets for wine in Australia, changing not only the way we drank wine but, also who drank it. The success of Barossa Pearl quickly saw the release of a range of imitators such as, Sparkling Rheingold, Pineapple Pearl, Starwine, Cold Duck and many more.

Innovation, higher quality and new varieties and styles drove a great change in the Barossa Valley in the 1950’s and 60’s; Yalumba purchased the old Pewsey Vale vineyard in the Barossa Ranges, first planted in the 1840’s and they were soon experimenting with cool climate Riesling and Cabernet Sauvignon; Orlando planted its now famous Steingarten Riesling vineyard on a windy, stony hillside and John Vickery began producing his legendary Riesling from Eden Valley fruit at Leo Buring.

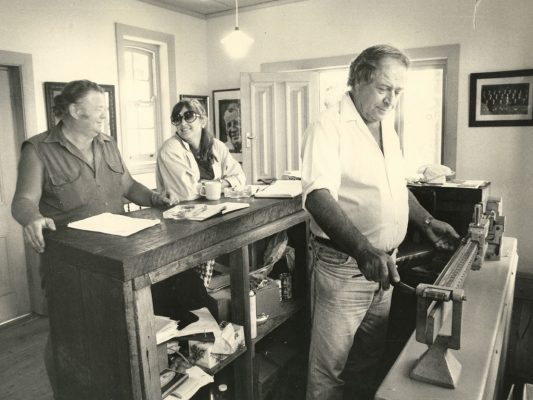

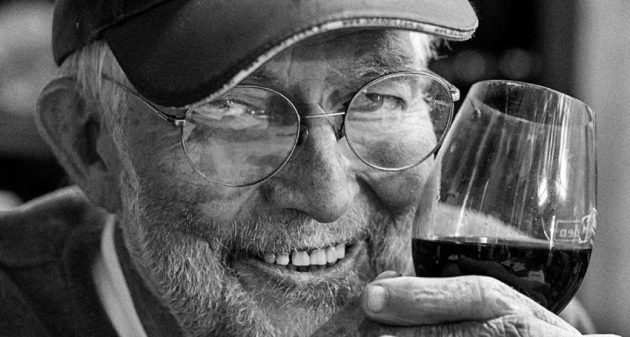

A young local named Peter Lehmann finished his apprenticeship at Yalumba and took on the role of Chief Winemaker at Saltram winery. It is hard to imagine any winemaker past, present or future that will ever have such an impact on a wine region or endear himself to grape growers in quite the same way as Peter in his beloved Barossa Valley. Peter passed away in June of 2013, a truly great Barossan.

Buy the 1970’s, the Barossa had reorganized itself and was enjoying success as Australia’s premier wine region. Wolf Blass has begun producing red blends that were the stars of the national wine show circuit and yet, such was the pace and scope of change that not all were able to go with it. During this time a many families and generational vignerons were ‘brought out’ by corporate entities: Reckitt and Colman purchased Orlando, Dalgety purchased Krondorf and Saltram, whilst Tooth & Co Brewers purchased Penfolds.

These new entities introduced mechanization and new efficiencies to the wineries, but it came at a cost, namely with loyalty and goodwill to the local growers as cheaper fruit was soon being trucked in from inferior regions. To make matters worse for some of the old family owned vineyards, the mid to late 1970’s say the national palate take a sharp swing to Moselle style off-dry white wines and then in the eighties to dry white Chardonnay wines. The demand for red grapes in the valley plummeted, families and old Barossa vineyards were now at great risk.

Peter Lehmann would become known as the first ‘Baron of the Barossa’ and he was much loved for his wit and wisdom, Peter was born in the region to the local pastor in 1930, he began working in the wine industry in 1947, aged 17, In 1960 he moved to Saltram Wines, where he was chief winemaker for 20 years.

Robert Hill Smith, managing director of Yalumba Wines stated” Peter Lehmann was an extremely talented, intelligent man who never got ahead of himself. He was a unique character, a true Barossa man who was a mentor to so many people. During a lifetime there are one or two people who have an amazing impact, he was one, and I can’t see anyone around to take his place.” Hill Smith also noted, “Peter was a handshake man, no contracts were necessary and he was not a selfish man.

He had a wicked wit, was irreverent but, he left a lasting impression whether you met him for just five minutes or half an hour.”

A very gifted winemaker who would go on to win a slew of trophies and the highest awards both in Australia and abroad, Peter’s legend and true hero status began in 1978 when multi-national company Dalgety, (now owners of Saltram) told their young chief winemaker to stop buying in grapes and concentrate on their own fruit.

With the livelihoods of over sixty grape-growing families at stake, Peter quickly put his own future on the line by setting up a wine company on the side and promising to take the grower’s crops at fair market prices. He did this for the next two vintages, by the third he’d quit Saltram and started his own label.

Fellow wine legend Wolf Blass described Lehmann as a “bloody good bloke who will never disappear. He absorbed the grapes that no one wanted. He became the savior of the Barossa Valley and they have supported him ever since,” Mr. Blass said.

Peter took a massive gamble that history now shows paid off handsomely, with Peter Lehmann winery at its peak taking fruit in from over 140 growers across the region, the brand famous around the world and the company being sold to the Hess group in 2003, (the year after Peter’s retirement) for over 100 million Australian Dollars.

Today, the Barossa Valley in South Australia is regarded as one of the World’s truly great wine regions and with some of the oldest commercial vines still in production, it is a living treasure of the wine world. I remember Peter Lehmann as someone who saw people faced with ruin and was deeply moved and then he decided to do something, at great personal, professional and financial risk. He championed a cause and became the champion of a region when it was on its knees. Some still declare he saved it; he will never be forgotten for his heroic deeds, his legend will only improve with time, just like the very vines he rescued and the wines they produce.

Peter Lehmann was awarded the Order of Australia for his contribution to the Australian Wine Industry and received an International Wine Challenge Lifetime Achievement Award in 2009.

The Vine Pull Scheme

Through the 1980’s the crisis facing the old Barossan growers and their ancient vineyards wasn’t over, the white grape Chardonnay was enjoying an extraordinary run of popularity outselling all other wines by as much as 20 bottles to 1 in the capital cities of the nation. Cool-climate Cabernet Sauvignon was fast becoming the darling of red wine drinkers and the market for fortified wines had all but vanished.

It seemed that the only home for tired old Shiraz, Grenache and Mataro vines was the cheapest possible ‘bag-in-box’ cardboard wine cask, prices for these fruit from these old vines had crashed and many growers were struggling to find buyers at all.

Growers were facing bankruptcy and many were faced with selling the family farm, farms that had been in the family since the region was founded. To counter this looming crisis, the state government of the day came up with a novel idea, subsidizing growers the cost of ripping out their old, unfashionable vineyards and planting them over to the trendier varieties of the day or, to planting alternative crops all together. The heritage of the Barossa has always been in its vines, tended to by up to six generations of growers, this was perhaps the region’s lowest moment.

Wine Writer, judge, author and critic Philip White writes of this time;

“The humiliation instilled by a large-scale vine-pull is deadly to those who must pull. I can’t forget the old men weeping openly in pubs in the Barossa in the mid-eighties, after they’d pulled their grandfathers’ gardens out. Pulling the vines was like pulling the teeth of the entire community, without anesthetic. Families fall to bits. Suicides occur.”

South Australia has never had a recorded case of phylloxera, the deadly mite that all but wiped out the European wine industry in the late 19th century. The phylloxera epidemic destroyed most of the wine grape vineyards in Europe, especially France when Phylloxera was inadvertently introduced by botanists in England who collected specimens of American vines in the 1850s. Because phylloxera is native to North America, the native grape species were largely resistant to it but, the European species had no defense. The epidemic first devastated vineyards in Britain and then moved to the European mainland, destroying most of the European grape growing industry. In 1863, the first vines began to deteriorate inexplicably in the southern Rhône region of France. The problem spread rapidly across the continent. In France alone, total wine production fell from 84.5 million hectolitres in 1875 to only 23.4 million hectolitres in 1889. Some estimates hold nine-tenths of all European vineyards were destroyed.

In France, one of the desperate measures of grape growers was to bury a live toad under each vine to draw out the “poison”. A significant amount of research and resources were devoted to finding a solution to the phylloxera problem, and eventually the main solution to gradually emerge was grubbing out the existing root systems and grafting vines onto resistant American rootstocks.

This meant that the Barossa Valley in Australia now had some of the oldest commercial Shiraz, Grenache and Mataro vineyards in the world and here was the state government of South Australia paying Barossa Growers money to pull their old vines out! Here was nothing less that the wholesale destruction of 100 plus year old, pioneer planted vineyards.

Unsuited to the Chardonnay grape and not a trendy cool-climate like Coonawarra or the Yarra Valley, the Barossa is once again in decline, production is shrinks and the future looks bleak.

Enter a small band of your winemakers and vignerons looking to go it alone and make a name for themselves. Following the Lehmann example, some were growers with great faith in their vines, frustrated by the lack of demand for their grapes, others were young winemakers sick of taking orders at big companies, wanting to go it alone and make a name for themselves in the world of wine and yet others were from outside the industry but just knew a good thing when they saw it.

People like Bob McLean, Charles Melton, Grant Burge, Robert O’Callaghan and Neil Ashmead.

They began buying up old vineyards destined for the chopping block mostly because they were cheap and all they could afford, or they brought out old wineries that had been running at a loss for years, picked up grape contracts for a song, taking in fruit that would otherwise have been left hanging on the vine or some trading their expertise in sales, brand building and public relations for shares in wineries going out backwards.

In Neil Ashmead’s case, the vineyard was thrown in as long as he purchased the homestead, some 20 odd years later and homesteads were being bulldozed over to create more land to plant Barossa gold, ‘Shiraz’ the very vines the state government was paying people to grub out!

Bob McLean called his Shiraz ‘Old Block’, it was damned good and as wine marketing goes, the rest is history, it started more than a labelling trend, it stared a movement in the vineyards, the wineries and the market itself both nationally and eventually, internationally.

Treating old vines as precious national treasures and as producers of super-premium grapes, allowing them to crop low with minimal irrigation and going back to hand harvesting, pruning and traditional winemaking techniques, such as using a basket press and an open vat fermenter, started turning out iconic wines such as Nine Popes, Rockford Basket Press and Meshach that commanded the attention of the entire wine world. Soon the Barossa was once again Australia’s most famous wine region, throughout the world.

Agriculture, by definition tends to follow cycles of boom and bust, the rapid growth in Australian wine exports through the 1990’s saw many small to medium producers over extend themselves in pursuing rapid expansion, favourable tax structures saw multi-shareholder investment schemes plant hundreds and hundreds of hectares of vines right across Australia, even before buyers for the fruit had been sought. At one point, it seemed everyone you met claimed to be a vineyard owner because they had shares in one of these schemes and at one point there were more grapes growing than there were enough wineries to process all the fruit! Soon the whole country fell into chronic over-supply of grapes, inflated grape prices crashed and many, if not most of the speculators had done their money and left with their tails between their legs.

In spite of a long period of oversupply and relatively flat market the Barossa had established itself as a premium region in the major wine markets around the world and its best producers not only survived but continued to thrive and then a new generation of sons and daughters and began to announce themselves to the world, forging their own paths and doing things there way.

Today the Barossa Valley is again enjoying a period of growth and prosperity, driven by quality wines, provenance and old vineyards on the supply side, whilst it is China and the emerging Asian economies that are largely driving increased demand.

Prue Adams of the Landline program on ABC television in a recent story noted that: “Chinese nationals are buying Australian vineyards and wineries at unprecedented levels, with up to 10 per cent of South Australia’s iconic Barossa Valley now in Chinese hands.” With one prominent real estate agent stating in the program that of his last seven winery or real vineyard transactions, six of them had been sales to Chinese parties and that at least half of the calls to his office were from Chinese interests.

The increased demand for Australian wine in China has driven the current purchases, with property buyers wanting to stabilize the supply of bulk and bottled wine for their Chinese market. Australian wine exports to north-east Asia increased 51 per cent in the past financial year and were worth $1.2 billion, according to Wine Australia.

Divide and Conquer

“Life existed in the Barossa for ages before anyone much cared about its wine, and that history keeps it feeling genuine, like somewhere you might drive to from Adelaide just for a few good meals, a spa treatment, a bit of sunshine. Then you stop in to see a winemaker—maybe Rojomoma’s Bernadette Kaeding, a talented photographer who displays her works beside her steel tanks—and drink an otherworldly shiraz that tastes like blackberries. And you realize you are in the midst of one of the world’s foremost wine areas.”

Bruce Schoenfeld, Wine Writer, Saveur Magazine

In highly evolved and sophisticated old-world wine regions like say, Burgundy in France every area, patch of soil or place is regarded to have its own characteristic or terroir, with all manner of plots and sites being given their own classification as a ‘climat’ or ‘Lieu dit’ to signify its uniqueness, even within a designated AOC, (protected designation of origin).

As the Barossa has become more widely planted, its history better recorded and its viticultural history better understood, specific characters that are uniform to a small area of the Barossa and significantly different to fruit from other areas has seen the emergence and identification of sub-regions within the valley.

The Barossa on a macro level is essentially two valleys the Barossa valley and to its south east the smaller, higher and slightly cooler Eden Valley, the two separated by High Eden Ridge.

In the Barossa Valley, areas such as Moppa, Ebenezer, Stockwell, Kalimna, Greenock, Light Pass, Marananga, Dorrien, Seppeltsfield, Stonewell, Gomersal, Bethany, Rowland Flat, Lyndoch, Angaston, Nuriootpa, Tanunda, Rosedale and Vine Vale, all produce fruit that expresses subtle, (and sometimes not so subtle) differences from the same varieties, (such as Shiraz, Grenache and Mourvedre).

Whether a winery bottles single vineyard wines to highlight these differences or blends to create complexity and balance, the Barossa winemakers have come to learn these nuances, look for them and utilize their expressions in their wines.

A look at Shiraz alone and one can identify a rich, dark cooking chocolate character in the fruit from Greenock, the bright acidity and firm tannins of Ebeneezer Shiraz, a certain tarry, inky richness from Rowland Flat and the legendary, aromatics, complexity and body of Marananga fruit.

The Barossa Valley’s cultural heritage remains strong with almost every village having its butchers and bakers, farmers markets, inns and restaurants.

Seppeltsfield Road

“…Seppeltsfield is a wonderful place, and is a great example of what can be accomplished by well-directed industry and enterprise. It has often been alluded to as the show place of Australia, and deserves the title, as for the magnitude of the works and the quantity and quality of wines, spirits, and vinegars produced, it is unequalled in Australasia…”

– Kapunda Herald, 3rd November 1905

From Silesian migrant to failed tobacco cropper, to wheat farmer, to famed vigneron; Joseph Ernest Seppelt planted his Seppeltsfield vineyards in the Barossa Valley in 1851 and by the end of his lifetime in 1868, it was a successful and burgeoning business about to complete the construction of a large stone cellar and gravity fed winery.

Joseph’s son Benno drove the winery on to being the largest in Australia, with extensive vineyards in the Barossa and expanding interests in Victoria’s Great Western District.

1878, saw the completion of the winery and cellar, which at the time of construction made Seppeltsfield one of the largest and most modern wineries in the world. To celebrate this milestone Benno Seppelt selected a puncheon of his finest wine and declared that the barrel would be allowed to mature for 100 years. This was the beginnings of the Centennial cellar and the world famous Seppelt ‘Para’ 100-year-old Tawny Port. Every year since 1878, the winery has set aside a substantial amount of its finest fortified wine to be matured for 100 years in barrel prior to release. In 1978, the first bottles of the 100-year-old wine were released. Seppeltsfield is the only winery to set aside such notable commercial quantities of wine, for consecutive vintages over the past 100 years, and nowhere else in the world does a winery annually release a commercially available wine that is a century old.

The Seppeltsfield fame grew, it became something of a village with winery buildings, stables, a distillery and most famously its avenue of Phoenix canariensis, a flowering date palm tree native to the Canary Islands of the coast of West Africa. Seppeltsfield went on to thrive as an artisan community, steeped in rich Barossan heritage, it was soon considered a true national treasure which helped shape the history of the Australian wine industry.

Over the ensuing 130 years, B Seppelt & Sons built a wine empire, producing fortified wines in the Barossa and sparkling wines and table wines at Seppelt Great Western in Victoria.

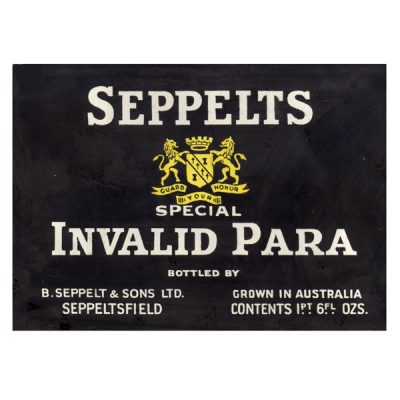

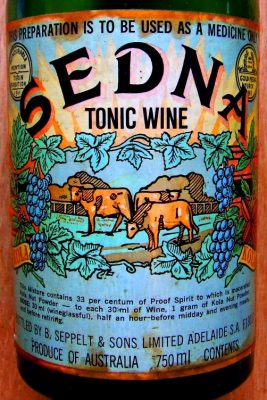

During their heyday, Seppelts produced several wines promoted for their supposed health-giving properties. An ‘Invalid port’ and a ‘Hospital brandy’ were frequently prescribed by doctors in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Other specialties were ‘Quinine champagne’ and ‘Sedna’, the latter a port wine containing extract of beef, kola nut, (high in caffeine) and coca leaf, (this is the plant known throughout the world for its psychoactive alkaloid, cocaine; although it should be noted that the alkaloid content of its leaves are considered to be relatively low). This concoction was produced by Deans, Logan & Co. of Belfast, Ireland, and marketed by Seppelts from around 1908. Later formulations had kola nut powder as the only advertised additive, the meat extract and coca having been dropped sometime around 1923.

After a three decades of corporate take overs left the brand on shaky ground, it has now been under the custodianship of one of its young star winemakers of the 1980’s and 90’s; the driven, charismatic and incredibly talented winemaker, Warren Randall. Randall took a 50% percent stake in the winery in 2008 and then began restoring the original gravity fed operation, taking a 90% stake in the company in 2013. Today Seppeltsfield is well on its way to re-establishing itself to its former and glory and beyond.

Under Randall’s astute experience and passionate guidance, there has been the release of a series of magnificent small-batch table wines, including reds crafted through the historic 1888 Gravity Cellar. The property now has over 420 acres of surrounding vineyard, many of them classified as Ancient Vines, historically significant winemaking buildings, majestic gardens and priceless architecture.

The property boasts twelve heritage listed buildings, 2000 Canary Island palm trees and over 25,000 barrels of prized fortified wine, maturing gracefully within the estate’s vast cellar holdings.

The artisanal village feel is also back with Seppeltsfield being a marriage of Barossan history, community and fine winemaking endeavor with it being home to the Jam Factory art and design studios and the critically acclaimed restaurant FINO @ Seppeltsfield completing the renaissance of Seppeltsfield Road.

The famous Palm Tree lined avenue section begins at the western entrance and was planted by Seppeltsfield workers during the great depression. The complete road is a series of straight lines and sharp turns through just over nine kilometers of the some of the most famous vineyard soils on the planet, dissecting the three legendary Barossa sub-regions of Seppeltsfield, Greenock and Marananga. The road encompasses 18 winery cellar-doors, internationally renowned culinary television personality Maggie Beer’s ‘Farmer’s Market’ and highly acclaimed restaurants Hentley Farm and Fino; all conspiring to make it one of the most picturesque and historically significant winery-drives in the world.

Marananga

The fruit from the Marananga sub-region, (sub-regions are locally known as parishes here) of the Barossa Valley has been called the region’s power-house, renowned for its incredible richness, weight, depth and intensity.

The little village of Marananga was known as Gnandefrei, (which loosely translates as free by god’s grace). Its name was changed in 1918 when, at the outbreak of World War 1, names of “enemy origin” were changed to sound less German. Marananga, which means, (my hands or with my own hands) in the Aboriginal language of the Overland Corner tribe was chosen as the new name given to the village and whilst some places have reverted back to their original names, Marananga has remained.

The Magnificent old Church in Marananga retains its origins with the name Gnadenfrei, St. Michael’s, Lutheran Church. According to its own historical records:

Many of the early German migrants who came to the country were there mainly as a result of religious persecution. In the early 1800’s there was no United Germany and the whole area consisted of a number of States, some more powerful than others. At this time Prussia was the largest and most powerful State and was ruled by King Friedrich Wilhelm III.

In 1808, by an Official Decree, he placed the Government of the Churches under a State Ministry of Worship headed by himself. In 1817 he issued an Order of Cabinet, which placed the Lutheran and Calvinist Churches under the one State Department.

A few years later he issued another Decree which united them into a New Union Church and bound them to accepting its New Confession. The result was that they were no longer allowed to adhere to their own Lutheran Confessions. He asked all Ministers to conduct services only in the manner laid down in the Agenda (Book) setting out the Orders of Service (Liturgy) which was compiled by himself with the help of his Political Advisers.

One matter to which Lutherans objected was that they were no longer permitted to administer the Sacrament of Holy Communion according to Lutheran Rites – a very grave matter of conscience to them.

As a final means of compelling Lutherans to submit to his demands, he passed New Laws in 1834 under which Pastors, who did not fully follow the King’s Agenda, were dismissed as well as being deprived of all Rights and Privileges. If they baptized, married and confirmed in the former Lutheran Manner, they were heavily fined. Midwives were compelled to report births of Lutheran children. If parents allowed their children to be baptized in the Lutheran Manner they were fined.

Those who refused to name the Pastors who officiated were jailed and rewards were given to those who reported the offending Pastors. Congregations were often fined heavily. Lutherans were “denounced publicly as rebels, separatists, dissenters and seducers”.

Those whose consciences compelled them to adhere to the old order of things worshipped in secret in homes, cellars, barns, forests and quarries and often did so at night. In place of Pastors who were arrested, Lay Readers often officiated. It is no wonder that they saw migration to another country as the only way out, as their pleas to Prussian Authorities for consideration and tolerance had been in vain.

On June 8th 1838 (after a failed attempt two years earlier), 250 persons boarded two barges to take them to Hamburg to embark on the sailing ship “Prince George”. On July 8th 1838, together with the ship “Bengalee”, they set sail for Plymouth, England, where they were joined by Pastor August Ludwig Christian Kavel.

The cost to transport these migrants to Australia was financed by a wealthy English Baptist Philanthropist, George Fife Angas, who at the time was Chairman of the South Australian Company. He was sympathetic to the situation of the Lutherans and was also seeking settlers for land in South Australia. Money for fares, etc., would be repaid over a period of time with added interest.

The migrants arrived at Port Misery (now Port Adelaide) on November 8th 1838. Pastor Kavel ministered to the German Congregations until his death in 1860. There were numerous other boat loads of migrants arriving in the months and years following. The first Lutherans settled at Klemzig (Adelaide),

but as more people arrived some moved to Glen Osmond, then to Hahndorf and Lobethal in the Adelaide Hills and to Bethany and Langmeil (Tanunda) in the Barossa Valley.

During the period from 1845-1850 more German settlers moved into the Barossa Valley area. Most of them had connections with the Langmeil Congregation and would have worshipped at Langmeil, Tanunda. Pastor Kavel was their spiritual leader. At this time, members of the Langmeil Congregation settled in and around the area which soon became known as Gnadenfrei. The Gnadenfrei Lutherans did not immediately form a new Congregation, but were regarded as part and parcel of the Langmeil group.

At some stage between 1850-1853 a local place of worship was built. This was done under the guidance of Pastor A. Kavel and remained part of the Langmeil Parish. The first church building was erected on the present church grounds, the land being given to the Congregation by a Mr. Carl Kriebel. The exact location and type of building is not known. These records were believed to have been lost with some of Pastor Kavel’s records.

In 1860 the Gnadenfrei Congregation severed its ties with the Langmeil Congregation and joined the Light Pass Immanuel Lutheran Parish, and remained with that Parish until realignment saw Gnadenfrei join a re-vamped Greenock Lutheran Parish in 1966. To this day the Parish comprises St. Peter’s Greenock, Nain Lutheran Church and St. Michael’s Gnadenfrei Marananga.

The present building was erected in 1873. Forty years later in 1913 the building was extended to include the existing gallery and bell tower. The bell in the tower was donated by a Mr. Leopold Schmidt in memory of his late wife, Sophie, as the inscription on the bell tells us.

It is believed that Mr. Schmidt also donated the original small bell to the church; this was then given to the church school, which was located in the house just east of the existing Marananga Band Hall. When this school was closed in 1916 during World War I, the bell was then loaned to the Marananga public school. When this school was closed in 1994, the bell was returned to the Gnadenfrei Congregation and is located near the front fence.

In 1938, to celebrate the 65th Anniversary of the church and the 25th of the erection of the tower, the existing altar, pulpit, a reader’s chair and matching lectern, altar railings, hymn boards, pedestals, silver candlesticks, and two leadlight windows were donated.